In certain corners of the internet, an idea has been gaining momentum: that social media has turned everyday life into one long, rolling series of self-inflicted embarrassments. Humiliation has become the currency of our digital age. It’s not exactly a new thought, but lately it seems to be hitting the nail on the head for more and more people – that creeping feeling that humiliation, or the threat of it, has become part of how we show up online.

The idea gets a name and some serious clarity in P.E. Moskowitz’s recent GQ essay, “Is Everything a Humiliation Ritual?”. What began as a conspiracy theory with QAnon overtones – that celebrities are ritually humiliated to appease hidden elites – has, in a roundabout way, captured an emotional truth many now feel, even if they’d never admit it: that every anxious post from Instagram to TikTok is a performance for an invisible audience that may love us, loathe us – or even worse, ignore us.

Moskowitz blames techno-capitalism’s monetisation of human emotion. Social platforms, they argue, create environments in which users willingly contort themselves into ever more extreme versions of themselves – louder, cringier, more exposed – just to be seen. It’s the natural byproduct of systems that reward emotional spectacle and penalise silence or nuance. Every post is a content hook. The algorithm is optimised to reward outrage, irony and visibility at all costs.

The result is what Moskowitz describes as a “mirror maze”. We enter social media hoping to express ourselves but instead see endless refractions – ourselves as we want to be seen, as others might perceive us, as the algorithm is training us to become.

All of this has consequences for how we think and feel. Our sense of self begins to dissolve under the pressure of constant feedback loops. We can no longer distinguish what we genuinely enjoy from what performs well. There’s a creeping suspicion that every gesture, every vulnerable confession, every candid moment is actually a kind of currency in a system we didn’t design but now can’t escape. Many people feel stuck in the performance economy, constructing their identities post by post – even when they’re hurting, bored or exhausted.

In this framework, the idea of “humiliation rituals” becomes less about grand conspiracies and more about structural inevitabilities. It’s not that anyone is forcing us to humiliate ourselves; it’s that we’ve come to equate being known with being exposed. And as the platforms escalate in speed and spectacle – driven by AI and metrics that reward extremes – we are coerced into ever more surreal displays of curated authenticity.

Ironically, the most private aspects of ourselves have become the most public-facing.

But what makes Moskowitz’s essay more than just a lament is their subtle call to resistance. It lies not in radical reform or mass deletion, but in something more personal and profound: the choice to be “cringe” in a way that’s unmonetised, unwatchable and unsharable. To do things not for the algorithm, not for visibility, but for oneself. Our Cringe = Sublime SEED touched on some of this — simply opting out of performance becomes an act of quiet rebellion. Going for a walk without posting about it. Writing a thought without tweeting it. Wearing an outfit without wondering how it will look on Instagram. These small acts chip away at the scaffolding of digital humiliation culture.

Systemic change will be needed too. Regulation around algorithmic transparency, data ethics and platform responsibility could push tech companies to design systems that don’t feed on psychological distress. Alternative networks – slower, smaller, more community-based – may emerge as viable refuges. But ultimately, the question that haunts Moskowitz’s essay is both simple and difficult: how do we live under the gaze and not be consumed by it?

The future of social media feels like it’s hovering on the edge of a vibe shift, as extensively discussed in SEED CLUB:

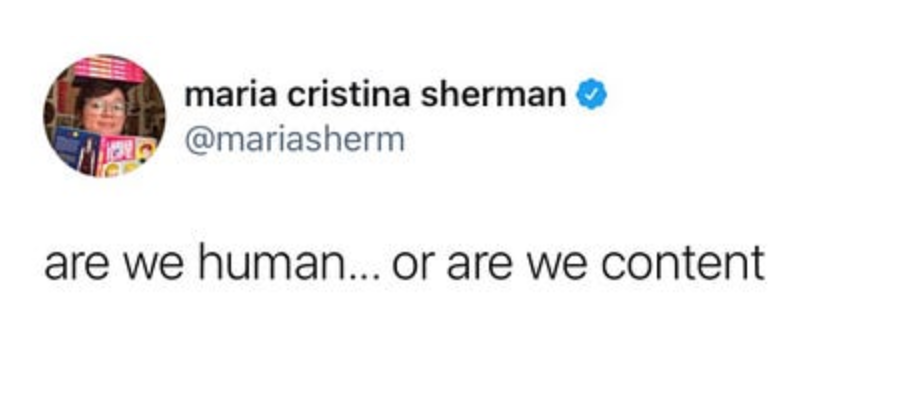

“If the problem is the model,” wrote Malena Roche, “then I would wonder if there’s space for a new type of disruptive social media network to arise.” Janne Baetsen added: “The very question – what is the future of social media? – keeps us tethered and reactive to an existing (dying/harmful) architecture.” And Shikhar Bhardwaj, jumping in later, casually dropped the phrase “Social Media Reformation” alongside the lead image. He also posted the tweet below:

So which direction are we moving in? Down the same old path – where identity is just content, content is monetised, and monetisation demands a steady drip of oversharing and low-key emotional collapse? Or could we actually start to build new ways of being online? Ones that prioritise people as people, and not just scrolling spectacle?

Until then, we’re stuck with the question that kicked this all off: is everything a humiliation ritual? Maybe not everything. But the more accurate question might be – how much of ourselves are we willing to give away just to stay visible? And when the likes dry up, what exactly are we left with?

| SEED | #8335 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 15.07.25 |

| PLANTED BY | PROTEIN |