The Viral Aesthetics of Poverty

Beyond the virality lies a legacy of defiant creativity, each object a quiet testament to resilience and meaning.

One of my earliest childhood memories is drinking my mum’s Milk and Kool-Aid mix when strawberry milk was out of our budget. It tasted rancid. But beyond that lactic betrayal, something else lingered in the taste: improvisation as survival.

Growing up, I also remember neighbours swapping hacks to make something out of nothing – like stretching meals with potatoes and soggy old bread – bathed in the flickering light of a TV showing a deformed love scene, fixed with a dry slap on top and a few careful tweaks to a bent coat hanger antenna. Signals of hope, barely caught. Life around us was a chimera of things made from other things. A hotchpotch lab of survival.

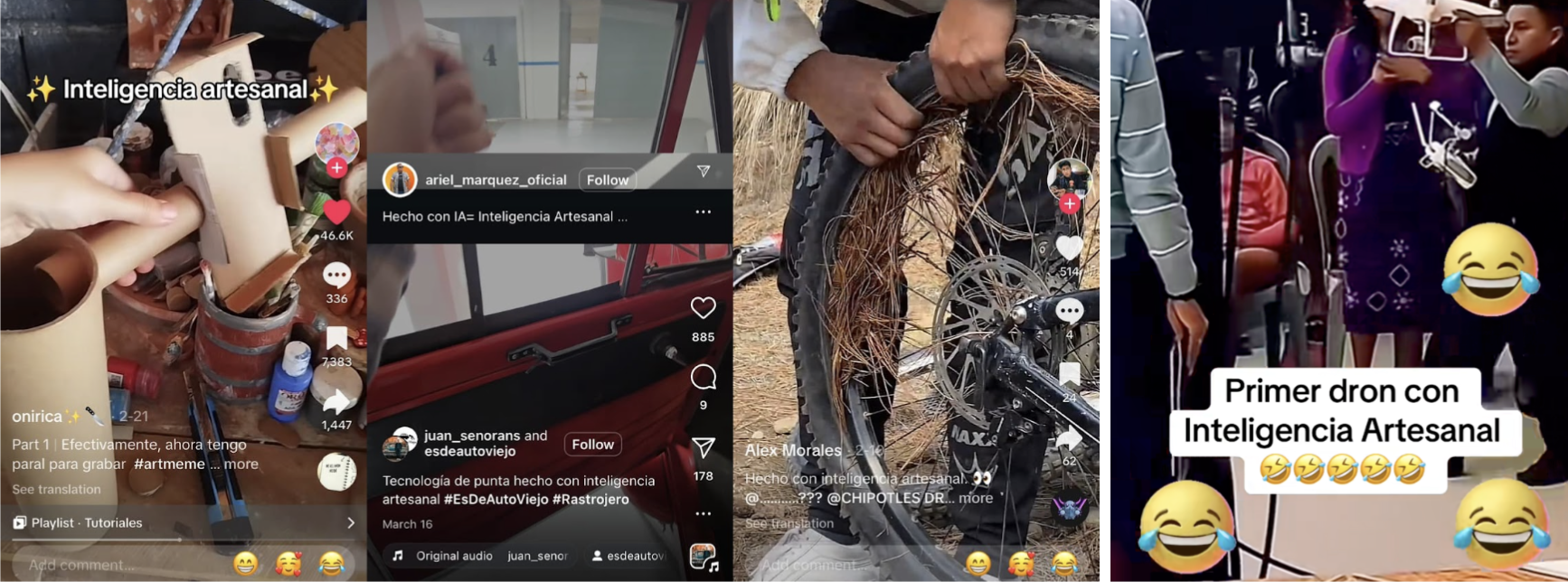

Years later, I see those same instincts reborn and rebranded online under the name Inteligencia Artesanal – a tongue-in-cheek response to the sterile promises of AI. Not an outright rejection of technology, but a reassertion of the irreplaceable wit of human invention in moments of scarcity. Visual gestures born from necessity.

This term, popularised through meme culture across Latin America, celebrates technological ingenuity powered by zip ties, tape and sheer willpower. Handmade inventions unafraid of the spotlight – or of failure – in a world obsessed with certainty.

Their unnatural nature carved out a niche in online culture, thanks to a blend of raw ingenuity, unplanned irreverence and the emotional weight they carry for those who grew up with these often-exaggerated utensils. We assumed every household had such chimeras – until we realised they didn’t. A true low-middle-class IYKYK moment.

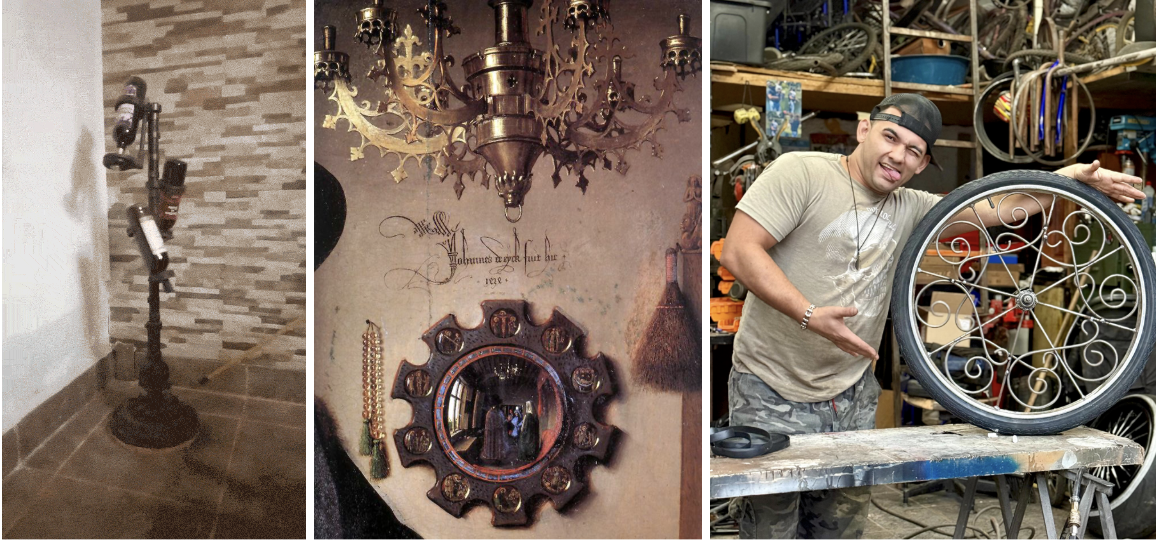

In mythology, chimeras were feared for being unclassifiable. But maybe that was their power all along. In a world where systems favour predictability and status depends on how well you can hide the ugly – the trash cans, the cables, the odour – Inteligencia Artesanal offers designs that refuse to be domesticated. Hybrid monsters born of desperation, cleverness and an unyielding will to adapt. They reject invisibility.

Cao Guimaraes, Gambiarra #59, 2007 (left) and meme.

We live in an age of cheap certainties: fast objects, flawlessly mimicked AI aesthetics. Maybe that’s why these strange, patched-together creations go viral. They carry texture. A relatable grief. The quiet trace of the person who made them. Beneath their irreverence lies a silent, collective mourning. A way of saying: I didn’t have what I needed, but I made something anyway. And this is mine.

Maybe part of us is starving for more mine in the mainstream. (Minestream?) What looks like failure might actually be the authorship of survival in disguise.

But is it actually an aesthetic? Maybe we just need to return to the root of the word – aisthētikos: perceptible by the senses. These creations demand that kind of attention. They’re not designed for approval; they’re authored by circumstance. And yet, they go viral. Why?

Because we recognise something real in them. Not design, but devotion. Not perfection, but persistence. A quiet refusal to disappear. An ethos born from elegant chaos – of things that weren’t supposed to exist, yet insisted on becoming.

Contrast and emotion, like wildflowers growing through the cracks.

Every country has its own version of this spirit: Colombianadas in Colombia, Gambiarras in Brazil, Jugaad in India. In the Philippines, Mag-isip ng paraan – “Think of a way” – is a mantra to live by.

Part humour, part critique. This is intelligence in the present tense: political by nature, beautiful by necessity.

Is this mindset industrialisable? Two examples stay with me:

- Alfredo Moser’s water-filled plastic bottles bringing daylight into homes in Brazil.

- Alejandro Aravena’s half-a-house approach to social housing – offering core structures families could finish and expand themselves, democratising the act of building.

These aren’t just cool hacks. They’re dignified improvisations. Futures rooted in community creativity, where innovation determines whether you eat or not.

From an artist’s point of view, this same spirit has shaped my current work. As an immigrant living in European limbo for nearly 2,000 days while waiting for a residence permit, I began a photographic series titled Bound Matter. Using found, low-cost and forgotten materials, I built temporary sculptural still lifes.

As a child, I turned wires, stones and trash into Transformer-like heroes. Play was survival. Today, that ethos lives in my creative workshops on grief and memory – spaces where I guide groups through complex emotions using sensory perception and guided reflection, bridging the gap between feeling and understanding.

Participants build vessels around personal objects they wish to honour. A button becomes a grandfather. A broken watch becomes suspended time.

They’re not asked to make something beautiful – just something honest, frugally innovative, true to themselves.

I’ve started to wonder: maybe what draws people to Inteligencia Artesanal, what makes it go viral, is a quiet, collective mourning. A grief for the times we had to make do. When ingenuity wasn’t a branding strategy but a way to stay alive. When invention came from need, not from an algorithm spoon-feeding us polished solutions – so seamless we forget to ask if we’re even thinking beyond the retina anymore.

But, yes, they’re also mega fun to watch.

So what if the real monster isn’t the chimera – but the system that taught us to fear it?

| SEED | #8323 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 03.06.25 |

| PLANTED BY | JON JACOBSEN |