The Detail Deficit

Pushing back against a culture addicted to efficiency and intent on flattening our senses.

Have you noticed how city skylines all look the same? That public objects, like park benches or lampposts, have become increasingly minimalist? Or how, instead of slathering their rental properties with patterned carpets and lace curtains, landlords now decorate everything in grey?

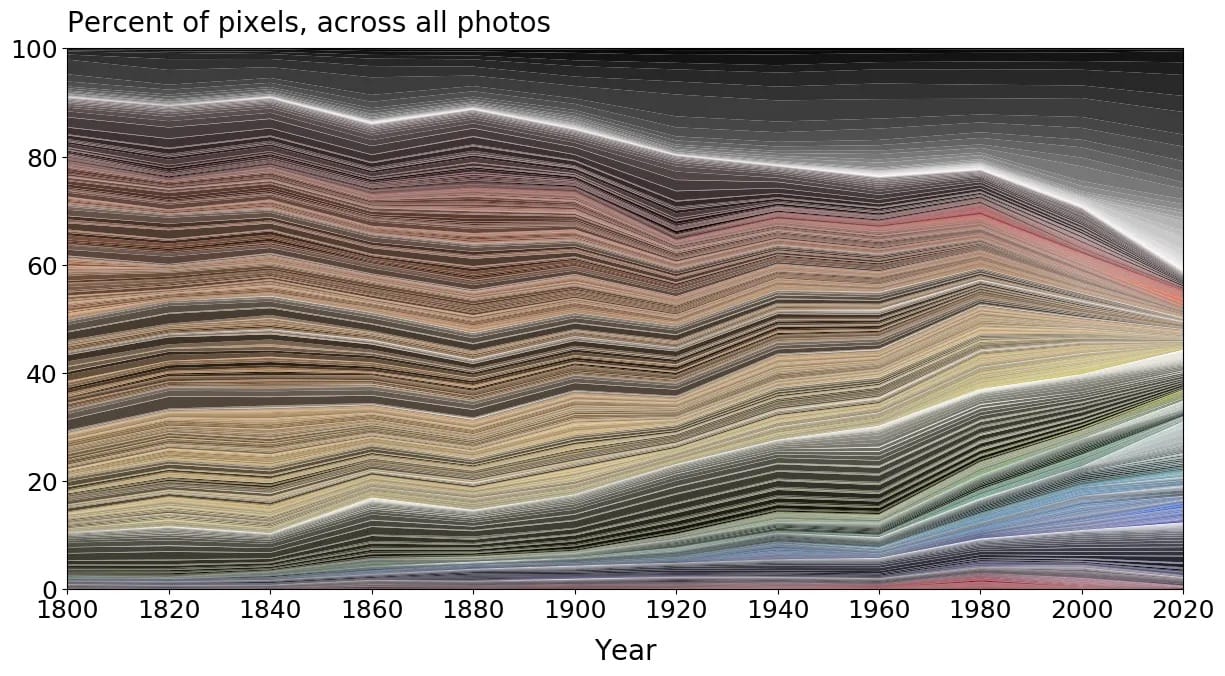

This isn’t just speculation. In 2020, the Science Museum conducted a survey of household objects over the past few centuries, finding that their colour and shape have become much less diverse over time. Everything is now monochrome and square, according to the survey, because everything is made from plastic.

As I sit across from my laptop, my supposed portal to a million worlds, I’m struck by how similarly flat the experience feels, the colours, faces and words all looping through the same few pixels. The objects around us are becoming increasingly utilitarian, with technology rendering our bodies more passive, and I’m noticing a significant erosion of detail: the aesthetic and sensory variety that gives objects and experiences their vitality, and the taste and agency that reflect our identities back to us.

Much like the “loss of aura” that Walter Benjamin described in Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935), this lack of true detail explains why even the most colourfully patterned dress that Shein can print onto polyester has no aura compared to the design it was ripped off from. It works in reverse too: the office block designed by minimalist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe holds far more significance than many thoughtless skyscrapers going up today.

Being surrounded by a world stripped of detail – objects with no aura, experiences with no friction – says a lot about the ideas shaping us.

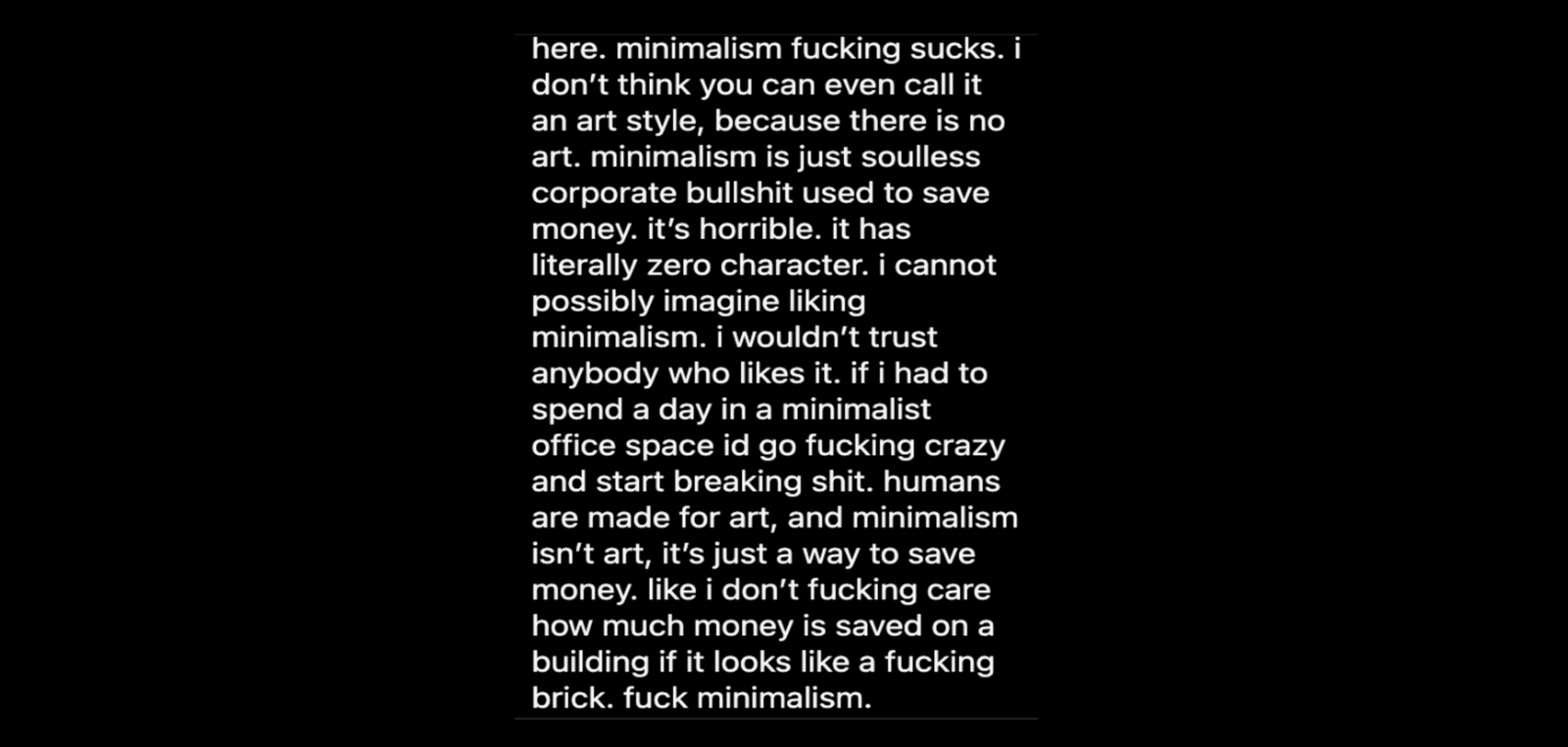

There’s a link between neoliberalism and the loss of detail throughout mass culture, because design has increasingly been simplified under capitalist incentives to cut production costs, broaden appeal and boost profit.

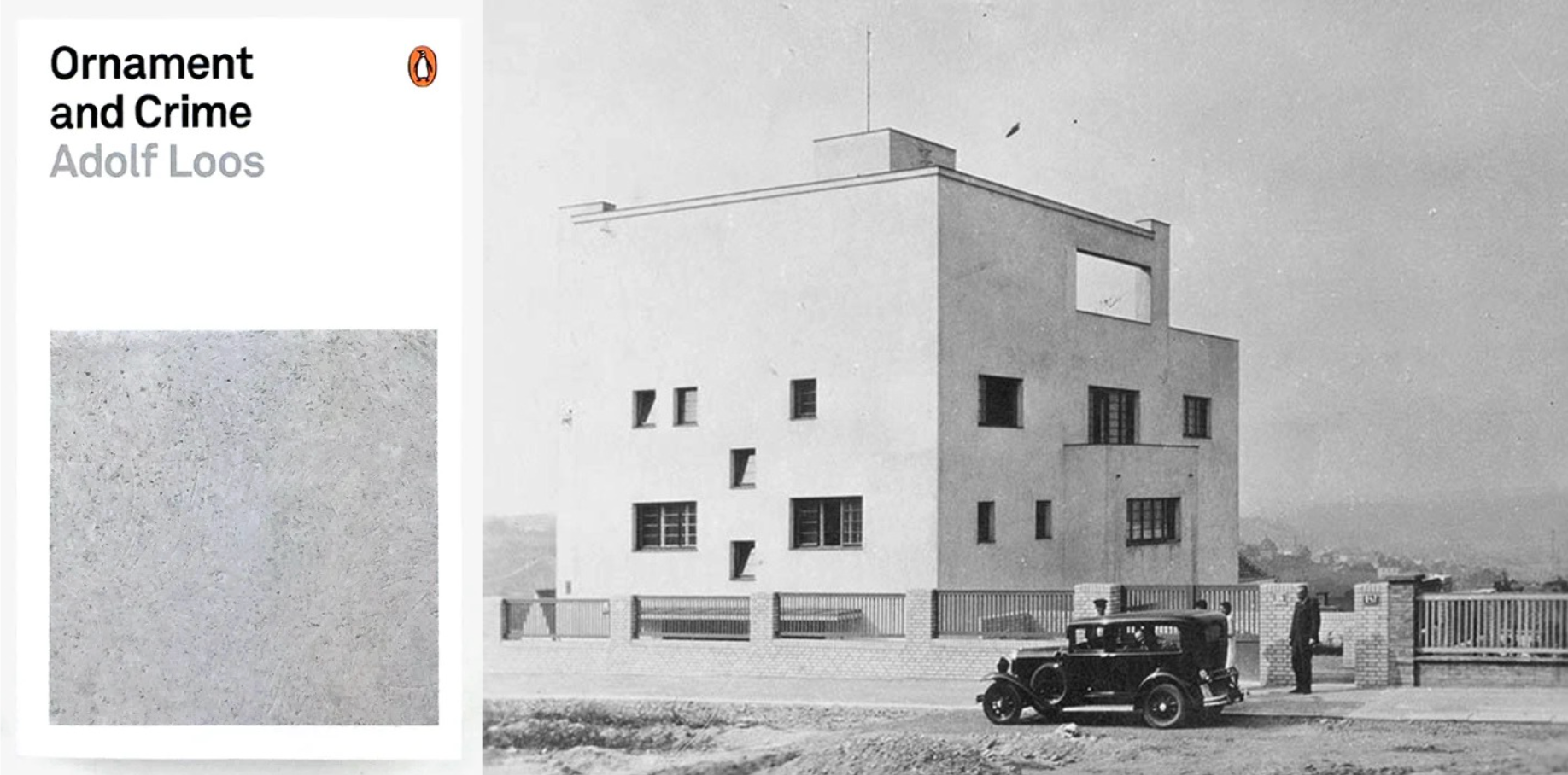

The drive toward efficiency extends beyond practicality. In 1908, Adolf Loos’ essay “Ornament and Crime” declared that “the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects.” Through its innate efficiency, a lack of detail became synonymous with progress and aspiration – sold to us as a marker for innovation, wealth and desire. We see it today in Apple products, white-box galleries, “quiet luxury”, the “clean girl” aesthetic – the list goes on.

But sceptics of capitalism have always found issues with these ideas. As Adorno and Horkheimer said in their 1944 essay, “Dialectic of Enlightenment”, “All mass culture under monopoly is identical”. Modernity’s pursuit of rational clarity – the will to strip away ambiguity, excess and ornament – has resulted in a world stripped of any meaning beyond its own capitalist goal. The result is a lack of detail now synonymous with homogenisation and optimisation. Where will this trajectory ultimately lead?

In his 2009 book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Mark Fisher wrote, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” He was describing a pervasive nihilism shaping a generation. Today his words feel even more resonant: in a world where so much is automated, packaged and simplified, the small human details can feel almost absent. We need more humanity – more craft, texture, friction. More detail.

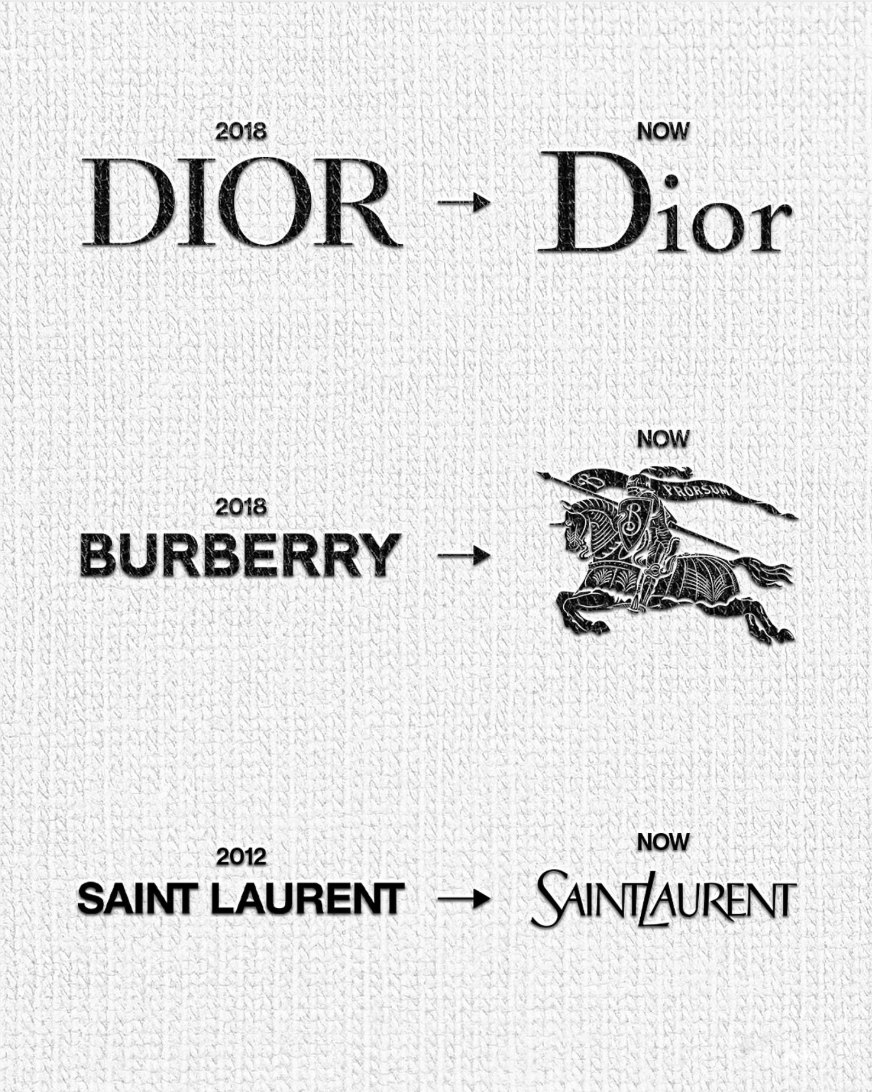

Lately, it feels as though more of us are searching for ways to break out of the flatness of modern life. Recent trends reflect a renewed fascination with analogue and tactile media – zines, vinyl, film photography, vintage tech. Multi-sensory subcultures like “cozy culture” or the perfume boom. The rise of “fourth spaces” – chess clubs, nature collectives, literary scenes, sauna raves, speed dating. Even design itself is shifting: brands moving from stark sans-serifs to heritage serif logos, like Burberry or Dior, that reinstate the rich origins of each fashion house.

But, as with any form of market desire, it is still shaped by the system itself. It’s perhaps unsurprising that detail, especially in products, has become a kind of luxury – the premium we pay for a house with “character” or for handmade goods. Similarly, the polished minimalism of quiet luxury aesthetics often overlaps with mainstream tastes and conservative ideals. By contrast, more maximalist, often thrifted or countercultural styles – though not untouched by commercialisation – tend to convey a sense of diversity, ethical awareness and a form of cultural or intellectual distinction, and often lean left.

So maybe this isn’t to suggest that we need more of anything, but that we need to experience what we do have more fully.

Susan Sontag’s reaction to the over-theorised art world of her day can now be applied to the total meta-abstraction of ours.

“We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more… In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.”

Perhaps it’s in more conceptual trends like “touching grass” or even “whimsical” culture – each defined by a joy in attention to detail and embodied experience – that we should look first. It’s here that we can begin to see a re-enchantment of the world: one that may not have all the answers, but at least re-empowers us with our own humanity while we find them.

| SEED | #8369 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 25.11.25 |

| PLANTED BY | LETTY COLE |