Sex And The Internet

In her new performance and book, Mindy Seu uncovers the overlooked histories shaping our digital lives.

Mindy Seu’s latest project, A Sexual History of the Internet, explores how sexuality, desire, identity and power have long been woven into the fabric of technologies. The project maps out an alternative history of engaging with tech – one shaped by sex workers, underground networks and the intimate infrastructures that influence how we connect, perform and express ourselves both online and offline.

Based between New York and Los Angeles, Seu is an artist and technologist whose work spans tech-driven performance, publishing and in-depth research into internet history and digital art. She also teaches as an Associate Professor in the Department of Design Media Arts at UCLA.

This conversation feels like a full-circle moment – I last spoke with Seu in 2023 around the release of the Cyberfeminism Index. Speaking to her again underscored how her work opens up overlooked histories, which can be especially helpful when thinking about the futures we hope to create within and beyond the internet.

Why did you choose a sexual history to explore?

After Cyberfeminism Index, which had so many themes – wetware, hacktivism, art, pedagogy – I wanted a clear through line that could stand alone. Sexuality felt right because it’s always been embedded in our technological devices. The adjective could be anything: a military history of the internet would still involve sex. It’s such a foundational part of how we think about embodiment, power and the messiness of our devices within physical environments. It became an entry point to talk about that sliminess, and also about power and its redistribution.

How is the internet slimy, and what does wetware mean?

Wetware plays off hardware and software – hardware being physical tools, software being code. Wetware originally referred to biotech and how computation or modification rewires our bodies. I’m using it more expansively, to talk about embodiment within digital environments, metaphors of nature, and how devices have become body appendages. It’s less strictly biotech and more about biology, physicality and inter-species effects.

Your work moves between digital and physical spaces – why are those bridges important?

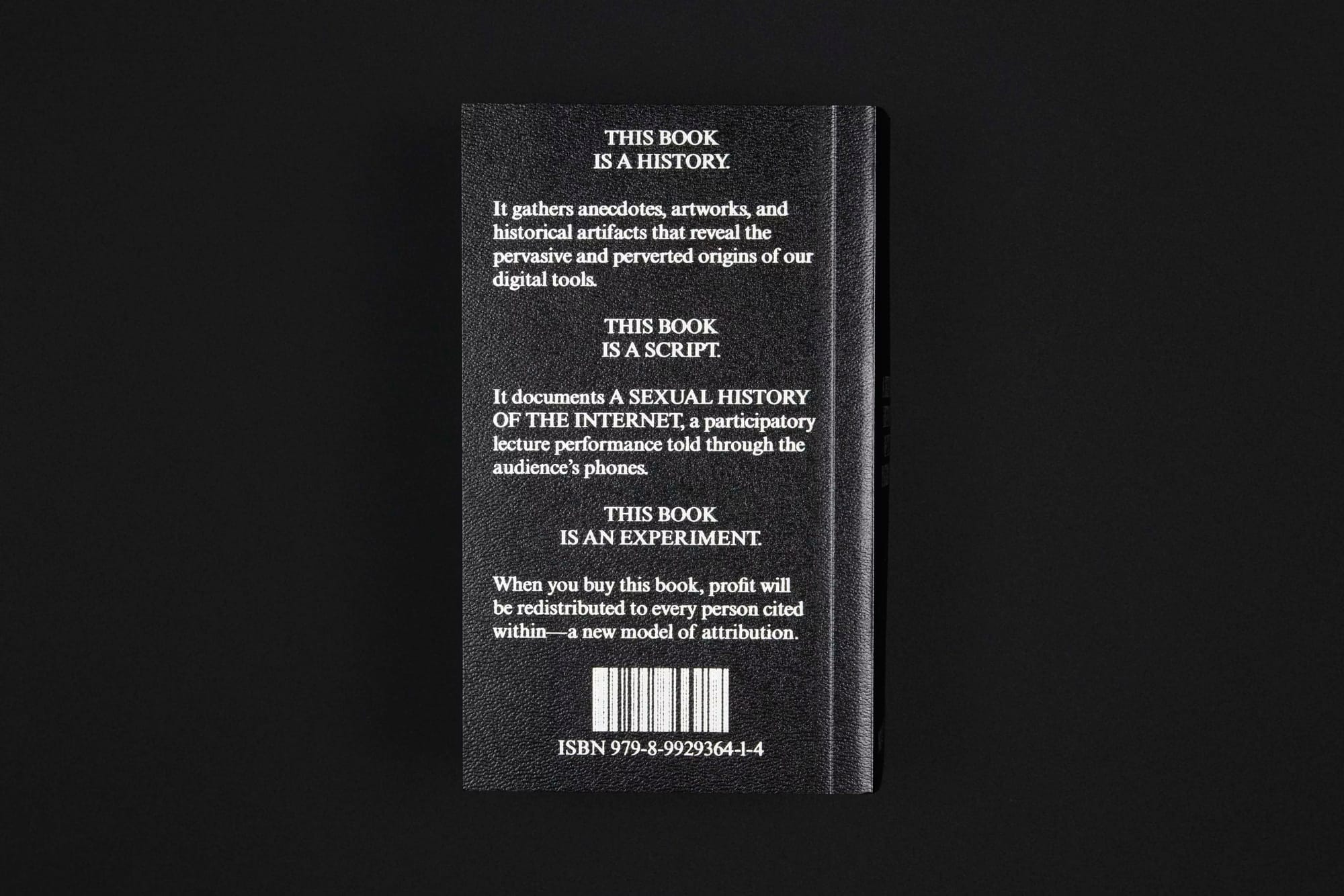

The translations show how entangled everything is. None of these media are siloed. Even in wetware or genetic modification, the body becomes something like a computer; and socially, we all undergo conditioning and can deprogram or relearn. That thinking extends to the work itself – Cyberfeminism Index existed as a spreadsheet, website, book and performance. A Sexual History of the Internet is a lecture, a performance, a book and also a redistribution experiment. They blur together.

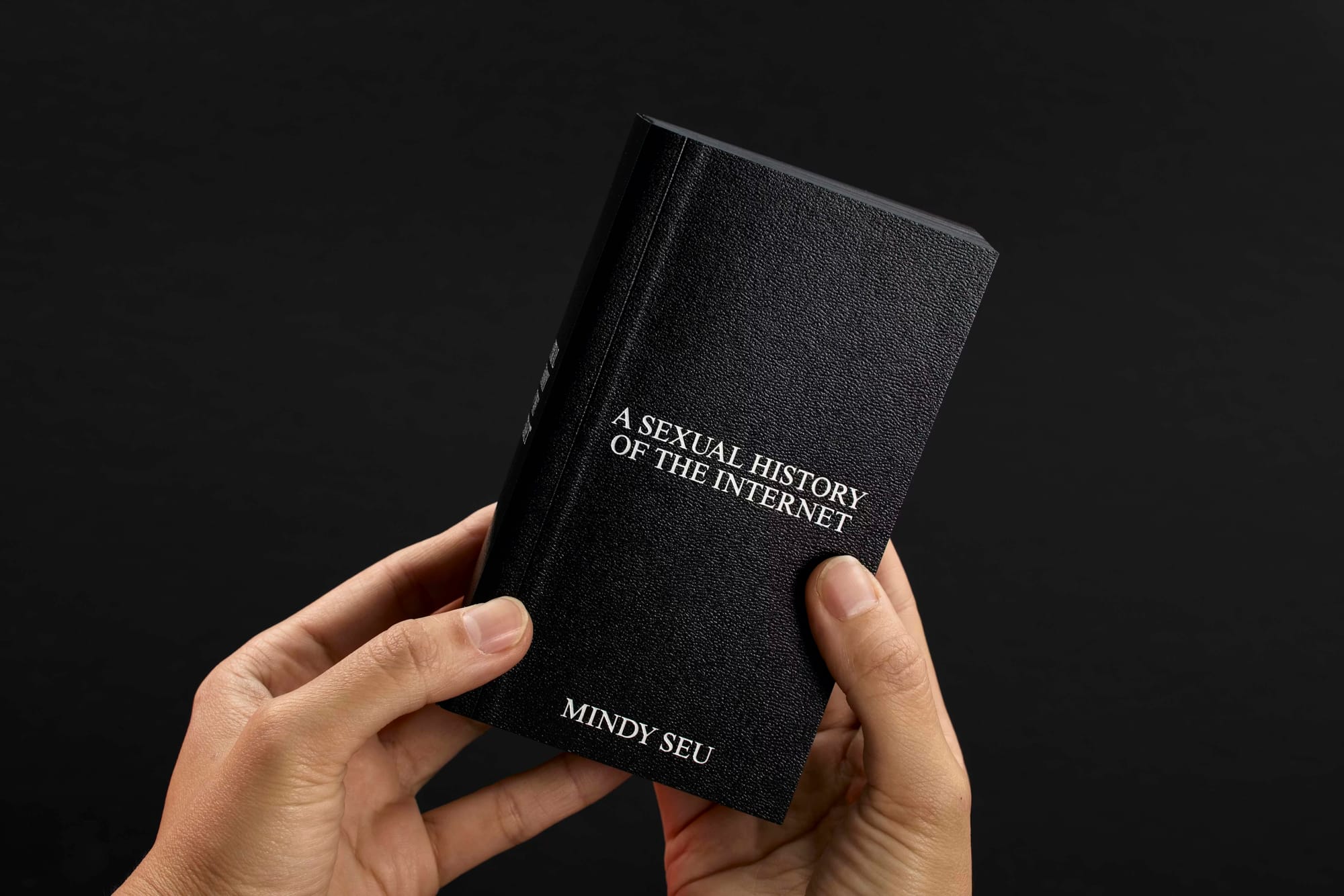

I love the tactility of the book – almost like the sultry sister to Cyberfeminism Index.

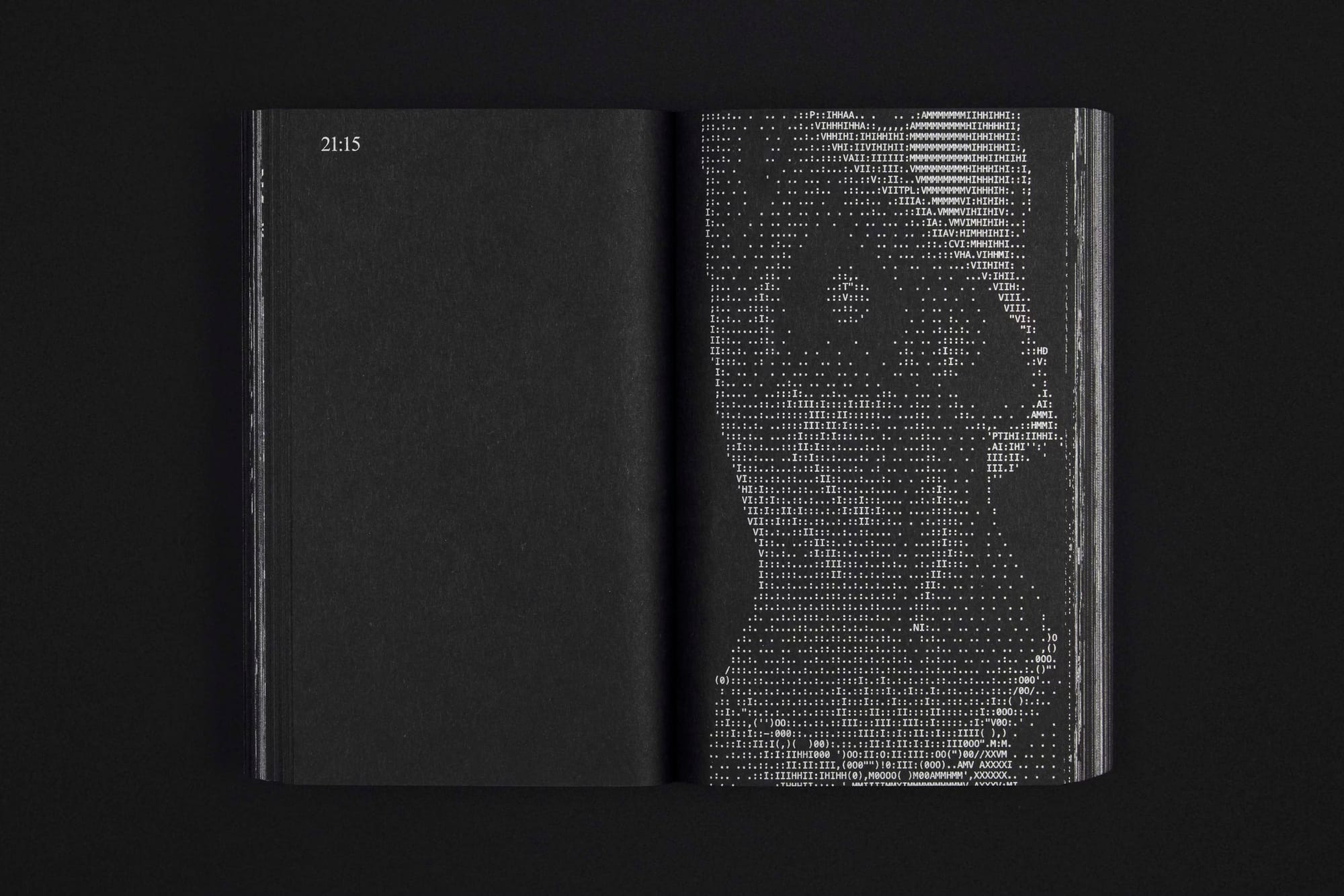

With Laura Coombs, who also designed Cyberfeminism Index, our references were: it had to be the size of an iPhone (since the performance takes place on one), it had to reference a little black book (which is why we picked the faux leather for the cover), and then it just started looking like a Bible – which added a sacrilegious but intimate element for your bedside table. At this point maybe every book I publish has to be three inches thick.

The flipping motion reminded me of scrolling. Was that intentional?

Yes. Most people who get the book won’t see the performance, so it requires its own physical footprint or proximity. The performance happens on an Instagram finsta: everyone’s instructed to click on the first highlight at the same time and then it autoplays for 40 minutes. Each text slide is five seconds; videos can be up to a minute. I feel like we’ve been trained to use apps like Instagram in very specific ways – to scroll and click as quickly as possible – but if you just click and watch, it almost starts to feel like an endurance test. So there’s a temptation to click forward in the performance, but the rules create a kind of power play. The book mirrors that pacing – you could read it in 40 minutes – and the snippets of text follow that five-second pacing. Even the “flip book” feel comes from using five-second increments of the videos. I’m glad it reads, because it’s essentially one long script, not an anthology.

People are overwhelmed with scattered digital memories. How do you archive your own histories?

I love print. I think print and web pair beautifully together. But I don’t have a perfect system. I mix hard drives, cloud and printed ephemera – but nothing is stable; AWS went down last week and all my sites were inaccessible. I don’t think we should save everything, but we can be more deliberate about what feels precious. Relying on institutions or curators to decide what matters means our histories are vulnerable. That’s why the book is “a sexual history” – foregrounding subjectivity. Anyone could write their own version. Mapping what shaped your political consciousness and pairing it with personal anecdotes shows how big historical moments impact individuals.

What were the most surprising or weird things you found while researching?

All the references in the performance and book link to our Are.na channel. Julio Correa was a grad student in my class at Yale, and he originally tested the Instagram Stories-as-lecture format. In 2024 we did constant beta tests for pacing, sound and what historical or anecdotal elements we should include. Early versions were an hour, which was too painful for phone viewing, so we cut it down to 40 minutes. Then Instagram kept deleting our finstas, so we learned to censor through algospeak and even discovered audio alone could trigger moderation. I wish it could be five times longer – there’s so much good media content related to this – but we focused on key historical moments and contemporary ones without a textual footprint, especially to write sex work more into the history.

How might the internet influence our sexual futures, especially with deepfake porn?

Deepfakes, VR porn and age verification show where things are heading. Even with AI-generated and problematic categories, there’s still a consistent desire for intimacy – people want to talk with performers, even if it’s a human chat assistant cosplaying as them. Search terms show how traditional desires remain; missionary is still the most common search on mainstream sites. Instead of blaming individuals, we should look at how systems shape desire and how individuals push back against mainstream platforms.

Any thoughts on legislation around deepfakes?

Artists point toward alternatives. Hanna Bear used a revenge-porn generator and found their false nudity locked behind a paywall. Sarah Friend trained an LLM on herself and lets buyers submit prompts she can approve or reject – so any generated “nudity” is consensual. Whether this could become mainstream is unclear, but it models different frameworks. Right now legislation mostly focuses on age verification and payment processors.

What about a sexual history of Web3?

Crypto appears throughout A Sexual History of the Internet. Some of the first people who pushed forward crypto currencies as a shippable product, not as a speculative product, were sex workers (for example, Spankchain). Of course, it’s because their work is highly policed on mainstream platforms, but I also think that many sex workers are natural innovators, regardless of the policing. Anytime you have a white market, there will be a black market, and people use the black market in regulatory ways or in more subversive ways. I think that having the option to have privacy and autonomy over how your money is spent and distributed is a really important impulse, which is why for a long time people thought Web3 was here to stay. Crypto is now entering legislation, so it’s not going away, although the metaverse clearly won’t become mainstream.

People feel grief around what Web3 promised. What do you think about Web4?

Web3 didn’t even fully happen, so jumping to Web4 feels strange. Web1 and Web2 had clear infrastructural shifts; we haven’t had that. I don’t really predict futures – I ground things in precedent. The metaverse has roots in early 20th-century military research; AI’s history goes back decades; decentralisation was part of Web1. I’m sure there will be historical echoes, and also clear examples of what not to repeat.

What nostalgia is worth carrying forward?

I miss discursive environments. When I was growing up with the internet in high school, I remember having long conversations online – I certainly don't do that now. Instead, you just get these snippets that are either validating or polarising. I really miss that sense of communal networking, those discursive spaces and the ability to make mistakes in public.

What will future historians find most fascinating or embarrassing about our internet?

Echo chambers. The splintering has changed politics and our discursive environments, and made it hard to talk across differences. I think that will only intensify in the next few years.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

| SEED | #8368 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 20.11.25 |

| PLANTED BY | KESIA INKERSOLE |