Rise of the Beer Makers

There is an old and wise Czech proverb that reads: ‘a fine beer may be judged with only one sip, but it is always better to be thoroughly sure.’

But the thoroughly established beer market as we’ve known it in the UK is changing. The honourable craft of brewing is coming to the fore in London with a group of new local breweries. And its swelling popularity can be aligned with a wider trend towards craftsmanship that has been spreading throughout a range of industries.

Like many a great idea, Ian Burgess’ eureka moment came to him in the middle of drinking a cold refreshing beer. He was on holiday from the UK in Australia, relaxing on a beach with a bottle of Coopers, one of the country’s finest hand-crafted ales. As he looked down at the bottle in his hand, he thought: “Why isn’t someone doing this in London? This would go down really well back in London Fields.”

And it did. Just last month, on a sunny Saturday afternoon, a crowd of East Londoners gathered at an old railway arch for the launch of London Fields Brewery, Burgess and his partner Jules Whiteway’s new microbrewery. Burgess is no stranger to the drinks industry. He made his name as the founder of London’s Climpson and Sons coffee, one of the pioneers behind the surge in local independent coffee shops. But with his latest venture, Burgess and Whiteway join a number of London-based entrepreneurs that have recently set up small-scale breweries.

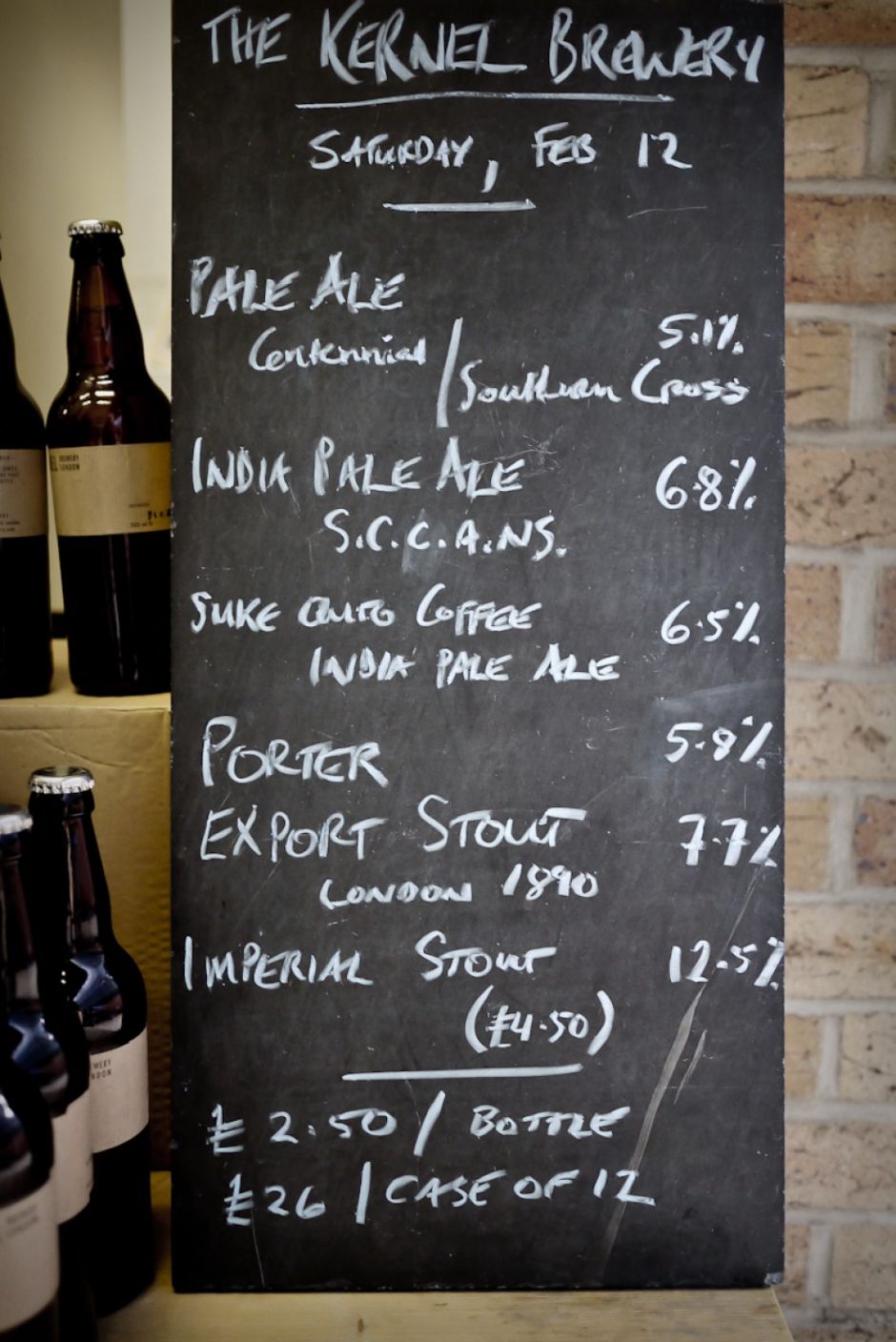

There’s The Kernel, standing in a railway arch on the increasingly popular Maltby Street Market near Tower Bridge. East London Brewing Company opened this summer in Bethnal Green. Redchurch Brewery is about to launch in Shoreditch. And there's rumours of a Hackney-based brewery opening in the next six months.

London is playing catch up to a wider small-scale real ale trend. Over in the US, particularly in areas like Portland, the craft beer trend is notably entrenched. With annual growth peaking in the mid-1990s, according to the Brewers Association, microbreweries now represent over 97% of America’s 1700-plus breweries, of which the ‘regional craft’ sub-sector is a growing element. And it’s grown beyond America, too. “In Denmark,” says Mikkel Borg Bjergsø, founder of the Danish Mikkeller Beer, “we had a 'beer revolution' 10 years ago. I think we’re seeing this same trend in UK at the moment: going from traditional towards experimental.”

There are a number of young drinkers - the hipsters - that are drinking these craft beers. These younger people are looking for something different, with full flavour and nice packaging.

Back in the London things are starting to stir. And behind this resurgence in small-scale beers is a new type of beer enthusiast, wanting something authentic and locally-produced. “There are a number of young drinkers - the hipsters - that are drinking these craft beers,” says Burgess. “These younger people are looking for something different, with full flavour and nice packaging.” Kernel forgoes complicated emblems for a minimal ‘stamped’ identity on its bottle labels. London Fields ties a simple brown label around the neck of theirs. It’s this simple, pared back and clean design that stands out from the crowd and catches the eye of these aesthetically conscious consumers.

These drinkers also find the local provenance of the beer appealing, says Burgess - a key difference to older craft beer movements in London, which saw drinkers obsess over obscure imported US labels. “These new drinkers are really into buying local and supporting small businesses and community,” says London Field’s Burgess. This can also be understood by looking at the stockists for Tower Bridge’s Kernel beer brand.

It’s found in bars and pubs, but also the city’s growing number of local cafés such as Railroad in Hackney and Look Mum No Hands, a popular stop-off for cyclists in Clerkenwell. “People are getting more interested in good beer, and good beer is becoming more easily available”, says Evin O’Riordain, the man behind Kernel.As for the brewers, there is a kind of do-it-yourself attitude and aesthetic that’s central to their ethos. “I decided I didn’t want to do the same thing for my whole working life”, says Stu Lascelles owner of East London Brewing Company. “I wanted to work for myself”.

So many of these craft breweries in the UK and throughout the global fraternity seem to begin with a small group of friends and a desire to get hands-on and make great beer. It is this diversity that makes this new craft beer exciting; taking on board its tradition and past, but shedding the fetters and restrictive style-definitions of mainstream beer organisations. As Mikkel says, “It is all about the idea. If the idea is good, there are no limits.”

Hand-crafted charm with small-batch innovation are the new desired attributes – and this is something not limited to the food and drink sectors. With creativity and authenticity, marketers can successfully position themselves within this growing and frankly exciting trend. At its heart is the image evoked from small producers shaping traditional wares by hands – beers, cured meats, furniture, denim, wine – treating production as a craft.It is about quality over quantity, certainly. But more than that, it is a focus on products that are made with passion. It is an ethos brought to creation, branding and industry that consumers are becoming attracted to across the board.

So perhaps it’s time for everyone, and not just this new generation of brewers, to get a little more hands-on.