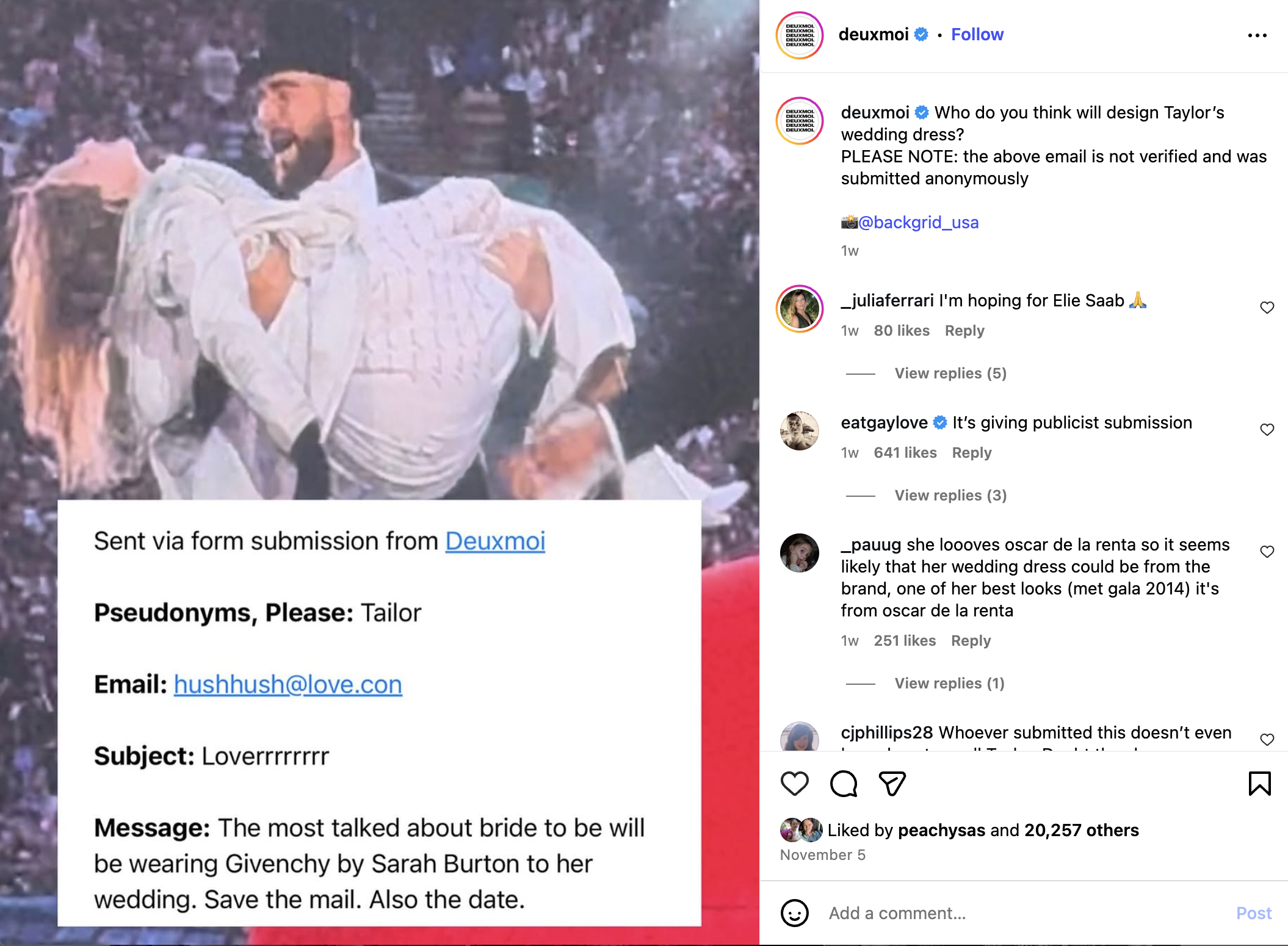

Ambiguity Maxxing

In a world obsessed with likes and followers, people are increasingly choosing mystery – keeping secrets and making you work to get them.

Humans love a bit of mystery – an air of inscrutability. But it’s hard to keep anything a secret in a world that documents everything.

We know things that we shouldn’t: celebrities’ inside jokes and Robert DeNiro’s martini order. Social media once encouraged this kind of intentional overexposure. We shared everything in exchange for attention. But a growing number of people are starting to move in the opposite direction.

In the Financial Times, journalist and editor Jo Ellison asked, “Have you switched to private yet?”. The New Yorker recently declared, “It’s Cool to Have No Followers Now,” in an essay by Kyle Chayka. That piece pointed to a recent Blackbird Spyplane essay titled “Now that’s how you post”, which praised Miu Miu stylist Lotta Volkova’s truly inspirational approach to the grid:

“Namely, she posts a barrage of grid pics throughout any given day. Rarely ‘dumps’ – she likes to stand on business and share 1 pic per post. Here’s the thing: Volkova has half a million IG followers, and a small-minded engagementcuck might note that while some of her posts get ~4,000 faves and others get ~3,000 faves, plenty get ~200 faves, and lots of them get ~100 faves. But does Volkova care? It doesn’t seem like it. The upshot is a highly chadded, gridflationary approach to posting. We could all take a page from her and go ‘G.P.S.’ Mode – just let the Grid Pics Spray.”

Elsewhere, the internet multi-hyphenate Anu Atluru posted to X in September, “Being a legible person has diminishing returns. You need a little mystery, a dose of unpredictability … to keep your story perpetually unfolding.” Atluru models this herself, posting cryptic-yet-thoughtful observations that seem to apply to everyone – and no one – at the same time.

Jackson Dahl is building something similarly illegible. A year ago, the investor launched a podcast, Dialectic, which he describes as “conversational portraits of original people”. The guests aren’t all from the same industry or clique, and the questions don’t follow a particular pattern. In one episode he says, “there will be a time for legibility, but right now, I’m in the oven.”

There’s something compelling about this kind of intrigue. We’ve grown used to squeezing as much context as possible into 280 characters, labelling ourselves (and our brands) as clearly to attract the right audience. But this is something – or someone – you need to engage with continuously to even begin to understand. By extending that process and building in ambiguity, you stop the work from becoming obsolete.

As someone must have said: if all your cards are on the table, the game is probably over.

It’s no coincidence that this shift is happening at a time when multi-million-follower counts have lost their reverence, their sheen dulled by bots and an increasingly transactional follower-followee relationship. As Chayka notes in the New Yorker essay, it’s the accounts with “a conspicuously modest following” that now hold a “certain cachet”.

Chayka traces this to a post-lockdown phenomenon. The pandemic made users so reliant on algorithmic recommendations that it was easier for creators to game the system, go viral and cash in. Now, it’s hard to separate “cultivating an audience” from “trying to turn a profit”.

This disillusionment with followers could be why ambiguity-maxxers are choosing to share less of themselves. It could also be linked to the increasing presence of AI. Perhaps it’s an anti-slop instinct – a subconscious rebelling against the research paper that birthed this wave of AI (“Attention is All You Need”); perhaps it's a refusal to be ranked or defined by an ever-changing algorithm, or a desire not to become part of its training data.

Maybe they’re simply focused on something deeper, rather than trying to sell you something. Cultural soothsayers Matt Klein and Remi Carlioz call this Camouflage Culture:

“A social immune response to a panoptic gaze of social judgement, audience capture, thirsty ‘How do you do, fellow kids?’ brands, permanently-recorded life and attention-seeking algorithmic conditioning. This is desperation for distance again. Sincerity. Earnestness. Depth.”

Camouflage Culture is the dinner party you’re not invited to, Substack paywalls, algo-speak, double meaning emojis, linguistic drift and slang, Chatham House Rules, dumb tech, three hour podcasts, IYKYK, ephemerality, anonymity, vibes, group chats, off-off-broadway, Yondr phone-locking pouches, the One Piece flag, deep-fried memes, Skibidi, niche subreddits, members-only clubs and printed zines.

Beyond the Dark Forest theory – fearful retreat from the online public – Camo is strategic opacity, obfuscation and resistance: culture that refuses to be easily readable, trackable or sellable. They suggest that Camo Culture has become synonymous with good taste, not least because of the exclusivity that comes with it.

It also takes a certain amount of privilege to make yourself inaccessible.

Bottega Veneta, for example, left social media in 2021; younger, smaller brands wouldn’t be able to get away with such a move. But it is possible to build mystique without logging off entirely.

“Put friction in your communication,” writes Future Commerce co-founder Brian Lange. “Make people work to understand what you’re doing. Let them be wrong about your intended effect. Let there be many judgments about what you mean.”

Resist the urge to share everything. Create for a micro community, not the macro. Make people ask questions about you – questions AI can’t answer. Hide in the corners of the internet the algorithm has no shortcut to. Have inside jokes. Be illegible. “Keep secrets,” Lange writes. “Some things are only for you and a few others until the time is right and the time is agreed upon to reveal them (which may never be).”

This is what the enigmatic collective MSCHF has been doing for years. From the Big Red Boots to the Museum of Forgeries, MSCHF’s work never comes with a clear explanation of why it has done something. This is partly because it is lazy, co-founder and CEO Gabe Whaley explains on the Dialectic podcast (“it takes a lot of work to document and tell a story”), but mostly because it wants the audience to impose their own meaning on the spectacle in front of them.

Internally, MSCHF has called this ambiguity maxxing strategy “the black box”. “We’re not transparent,” says Whaley. “Because the mystery lends more to the imagination than reality ever could.”

| SEED | #8367 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 18.11.25 |

| PLANTED BY | SOPHIA EPSTEIN |