Working the Numbers

If self-tracking can transform us as consumers, then why not also transform us as workers? We explore how data is making light work of our productivity

Big data has made its way into the modern vernacular. This is no surprise, as 2.5 quintillion bytes of new data are now generated every day. With all that information available, and with a growing number of ways to collect even more of it, employers are starting to imagine how it could be used to better understand their workplaces and improve worker productivity.

One way this is happening is through personal data – an idea pioneered by the Quantified Self movement, a group of tech-savvy consumers who track their sleep patterns, work out routines and even toilet habits. Employers have been inspired by this to learn more about their staff.

The sports world has been one of the first to benefit. Early this year it was announced that basketball players for two NBA Development League teams would be kitted out with tiny sensor discs weighing under an ounce each. These measure a player’s vital signs, recording cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health in order to build in-depth data sets and eventually improve tasks such as acceleration, deceleration and jumping.

In American football’s NFL league, players have worn sensors in their helmets and mouth guards that measure the strength of physical contact with other players, with the aim of developing better absorption material. It’s already had an impact on the game: according to Kevin Guskiewicz, co-chair of the NFL’s Subcommittee on Safety Equipment and Playing Rules, sensors played a role in the NFL’s decision to change kick-off distances in order to reduce player collisions.

Besides highly-prized sports professionals, people in regular desk-bound jobs will soon be tracked closely through wearable kit like the Nike+ FuelBand and Jawbone’s UP. Portland innovation firm Citizen has decided to track the health and happiness of its members of staff using self-monitoring devices such as Fitbit, RunKeeper and Happiily to understand how health and happiness might relate to their productivity. For instance, how the type of music genre being played in the office might affect the staff’s quality of work. Tracking can offer understanding of staff productivity in retrospect, but how do you improve it while they are on the job?

Other devices can deliver real-time data to staff who need instant information, such as to those in medical professions. A hospital in Boston recently equipped doctors with Google Glass headsets so they could instantly receive patients’ notes. Before they entered a patient’s room, they could quickly scan a QR code on the wall using the device, and patient information appeared in their field of vision. In mid-2013 surgeon Dr Christopher Kaeding performed knee surgery wearing Google Glass and the operation was live-streamed to his students. First responders in emergencies could also be equipped with Google Glass. Tech firm Mutualink has created software that enables crucial data to be seen in the field of vision, freeing the hands and allowing quick collaboration and data sharing in critical environments where seconds can make all the difference.

Google Glass could offer better customer service too. Imagine walking into a clothes store and immediately being shown items exactly to your taste by the Google Glass-wearing sales assistant, who is receiving real-time information based on your previous purchases. Airline Virgin Atlantic has already experimented with this idea. In February this year, it launched a pilot scheme where attendants in its Upper Class Wing at Heathrow airport in London used the devices to receive information about individual customers, including their ravel details and dietary requirements. Members of staff could give customers updates relating to their end destination, such as weather forecasts and information about local events, and have it translated into the customer’s language.

You’ll see employees also use this data to really understand what they should be doing and how they stack up against high performers, getting personalised feedback and tools to help them improve much more rapidly than we can today. Ben Waber, CEO of SocioMetrics

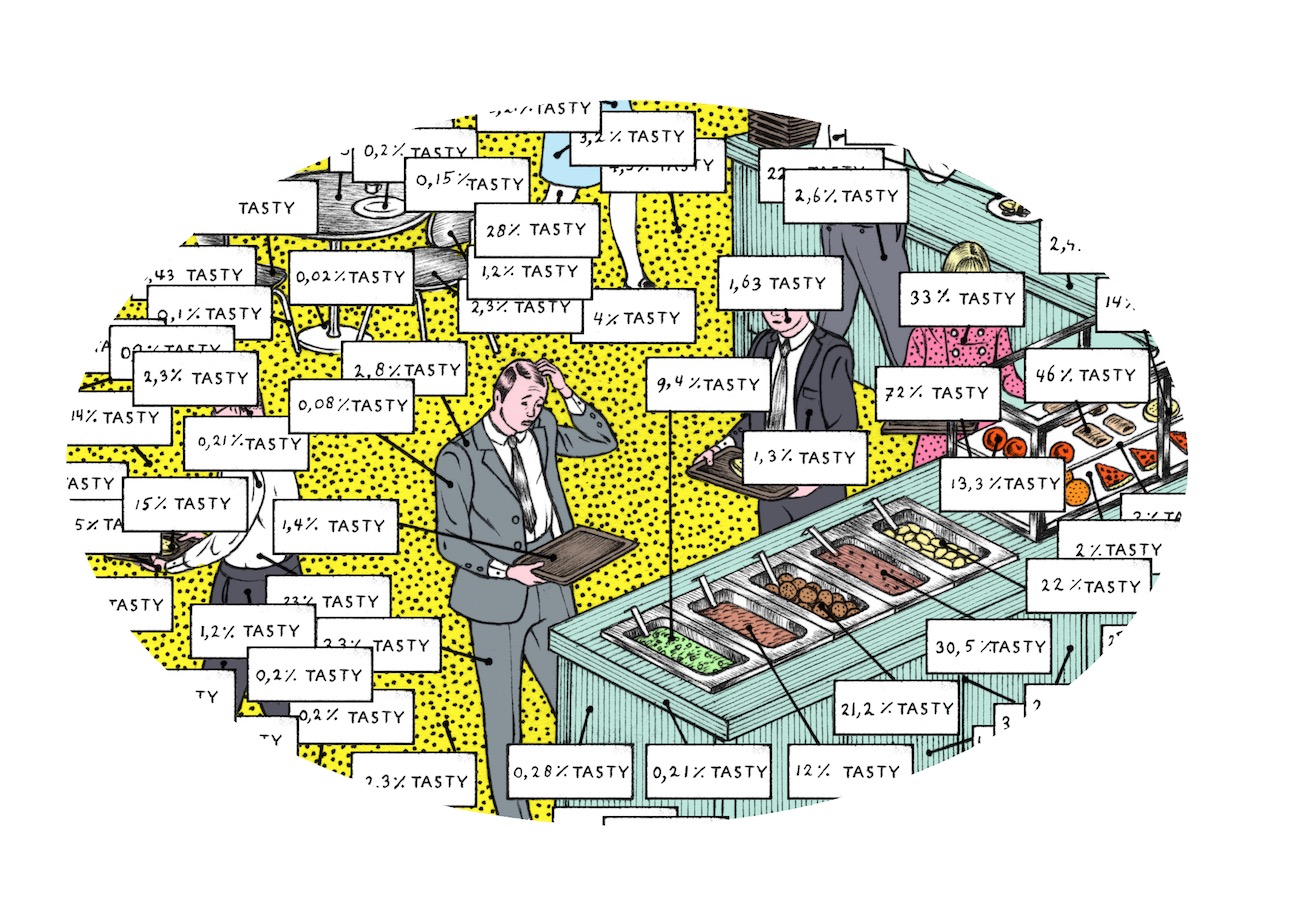

Data also offers an opportunity to motivate staff. One way is through gamification – the much-lauded marketing term where

video game mechanics are used to manipulate behaviour and where repetitive work tasks are turned into something altogether more rewarding. Imagine your daily task list is a sort of game that you actually wanted to complete. Foursquare proved a resounding success as it gamified people just being somewhere, and there’s no reason why such a model can’t catch on in the office.

IDC Energy Insights offers sensor-packed ID badges that allow companies to gather information about social patterns in the workplace. The data gathered enable employees to gamify their work, allowing them to compare how they stack up against colleagues. The company says that the gamification market is going to be worth billions.

“Early adopters will use that data the same way companies like Amazon are using digital data today,” says Ben Waber, CEO of SocioMetrics, a company that makes devices for workplace metrics. According to Waber, there will be a wider adoption of this kind of gamified data over the next five years, with workers increasingly able to view stats which are relevant to their role in an organisation. Just as Amazon has different home pages tailored to a customer’s needs, companies can apply this concept to the office and adjust according to what works.

“Companies will use sensor data to experiment with different ways of organising,” says Waber. “You’ll see employees also use this data to really understand what they should be doing and how they stack up against high performers, getting personalised feedback and tools to help them improve much more rapidly than we can today.”

Beyond performance, gamification can also encourage mindfulness in the office, such as being conscious about environmental issues. One example is Ecoinomy, which motivates staff to save money through eco-awareness. While software such as Hitachi Data Systems’ Jive network rewards user behaviour, Ecoinomy wants to encourage, for example, asking and answering questions.

It’s not just members of staff who are being equipped with data – so too are the places in which they work. Many new buildings today already feature built-in sensors that offer data on energy usage and other ways to keep costs down.

Design company Herman Miller uses a system called Space Utilization Services, where discreet sensors are placed in locations and record social-spatial interaction, offering the company a precise picture of the way these spaces are used by staff. It has led to the reorganisation of work spaces in favour of less individual and more collaborative environments – the sort of subtle adjustments that make a workplace function better.

Spatial analytics could become even more detailed with the introduction of Apple’s iBeacon, which uses small, discreet nodes that run on ultra-low-energy Bluetooth. The technology has the potential to provide data on how people move indoors, where they linger and why. By noting when people engage with an object, at which location and for how long, it could pave the way for providing unprecedented insights into social-spatial interactions. Robert Haslam of Mubaloo, a company which has already created a division dedicated to iBeacon, says the technology could offer greater insights when used alongside other sources of data. “What people are searching for, the apps they’ve got, and other data that’s available, could potentially predict what’s going to happen, predict trends or even deliver messages to people at the right time,” says Haslam.

If we are to see such growth in data at work, then something – or more likely, someone – will ultimately need to analyse it all. Futurologist Peter Cochrane believes new roles will be created specifically for comprehending all this new work data – not just for collecting and processing information but for understanding it in a social sense. “I think the big opportunity for moving into data is how you interpret it,” he says. “Social understanding as opposed to pure analysis or logic is going to find quite a bit of employment. The analogous situation is in warfare, where you have analysts coming up with scenarios but it’s the guy with the stars on his shoulders who has to make a judgement call.”

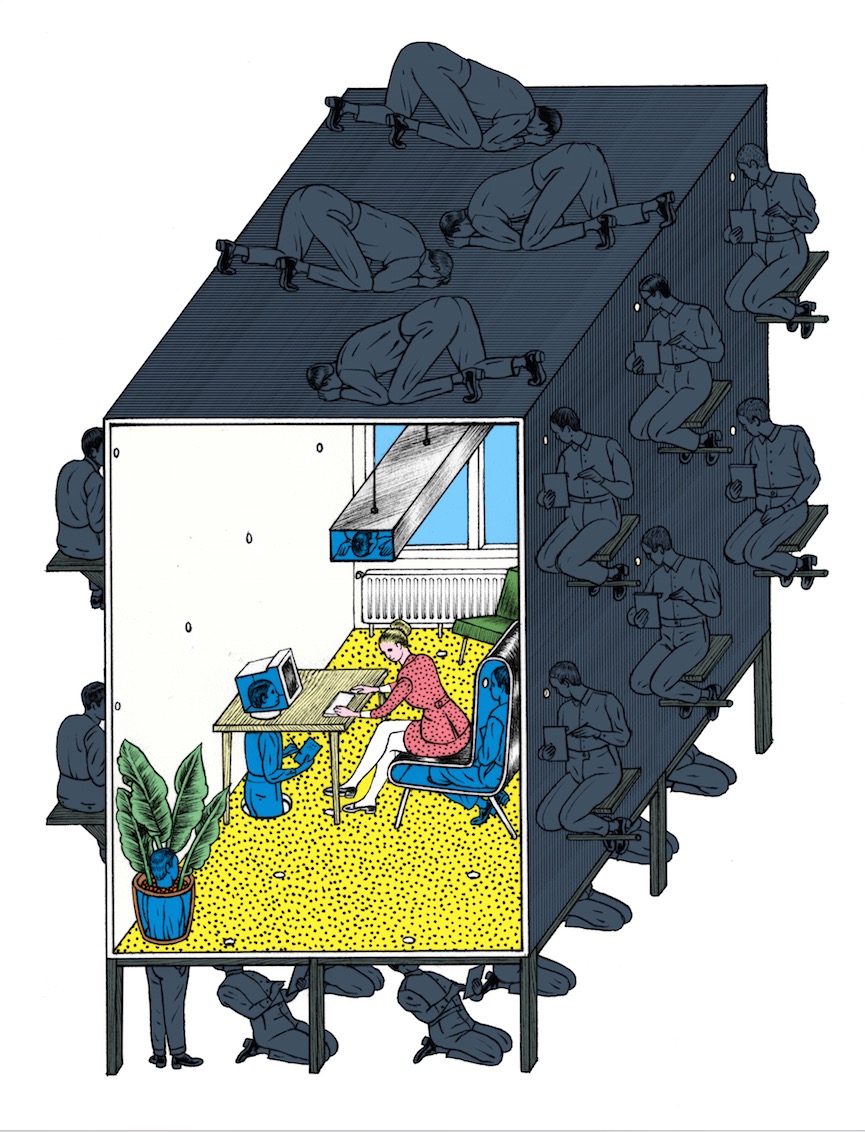

Then there is the inevitable issue of privacy: will we ever want to be closely tracked by our employers? Just because monitoring employees is possible doesn’t mean they’ll always be comfortable with it. Armbands that bark quotas at staff have already been introduced for blue-collar workers in warehouse picking. The press reacted with hostility to a Hitachi device that allows every aspect of a worker’s day to be monitored, from bathroom breaks to who they’re talking to and for how long.

Nick Pickles, director of privacy campaigner Big Brother Watch, says while there is value in the data it can certainly still be used to intrude on people’s privacy. “It’s essential that employees are part of the process and understand what is being done and how data can be used,” he says. “Monitoring doesn’t automatically mean problems go away – that takes good management, and surveillance should not be used as a solution to fix poor management.”

Companies such as SocioMetric promise that individual data is kept under lock and key. Other organisations, however, might not make much of these ethical considerations. Even if workers own the data generated, without strict company policy or even political legislation, the idea may not sit well with the workforce. If our workplaces are to be data-centric, it’s likely they’ll need to be so on the workers’ terms rather than on the employer’s.