Despite being a born-and-bred Londoner and an avid cyclist, my sense of direction, even here in my home city, is notoriously dire. That gag about not being able to find your way out of a brown paper bag? If behind every joke there really is a kernel of truth then, where exiting paper bags is concerned, I’m that kernel. Or at least that was the case until 2008, when the iPhone came into my world. Within days my hardwired sense of direction was upgraded. And since then, all those old excuses for getting lost or being late have been rendered null and void (save the odd drop in network or an unforeseen loss of power).

Yet I find myself burdened by a nagging concern: has this upgrade actually been such a positive transformation? Did I not maybe, just maybe, lose something precious – a strange form of innocence perhaps – in the process?

Amidst the furore of last month’s Apple/Google Maps debacle, it became apparent just how reliant the technophilic world has become on mobile mapping. Every iPhone user I met became outraged recently when they found themselves burdened with iOS6’s new (flawed) native mapping system – many of them the kind of folk who, in the pre-iPhone days, could have been counted on to always know which way was North, that this was the right road to take. Such is the power of the demure, all-knowing, ever-present digital map.

Centuries ago, when Medieval cartographers where drawing up maps of the cities that were blossoming around them, they were seeing the world from a perspective that was essentially untenable save for God-on-high himself. Yet at the close of the 1970s, from the vast windows of New York’s World Trade Center, this was precisely where the French philosopher and social scientist Michel de Certeau stood for his seminal The Practice of Everyday Life (1980), holding just that perspective: deific, all seeing, profoundly elevated. As he looked down upon Manhattan, he perceived the totality of the urban sprawl spread out beneath his feet. And that totality spoke to him. The passage of the many ant-like people that scurried around the squiggled streets below became a text for him to translate; the city’s living signature scribbled by the men and women at ground level, blind to the wider pattern and structure seen from above. A self-styled Icarus, de Certeau’s new-found height had made, in his words, “the complexity of the city readable.”

It is this synoptic stance, de Certeau argued, which is the viewpoint of urban organization. It is the perspective of governments and city planners: everything in its place, tidy, connected, colour-coded. And for today’s consumers, it has become the ever-accessible view offered unto us by Google Maps. (And Apple Maps. When it works.) We now see the city around us in terms of lines and grids. We have become, as far as the urban sprawl is concerned, as gods.I think it’s all too easy to get from one destination to another in such a way that you can remove yourself from actively being on that journey. But back when de Certeau was looking down on Manhattan, he saw too that there was a beauty in the blindness of street level interaction. He saw that we navigate the planned and structured city every single day in a manner inherently different to that of the all-seeing eye above. Where the city from on high is a thing of organization and permanence and ‘strategy’, for us down below it is a place of individual personalization and ‘tactics’ – we make of the strategized city what we will. We take shortcuts in the face of institutionalized planning. We discover. We revisit. We reshape. We get lost. Or at least we used to...

With the help of ever-accessible mobile mapping services, our cities have become hyper-organized landscapes built up on a foundation of efficiency. It could be argued that the ubiquity of live mobile mapping with its ‘locate me’ and ‘find destination’ and ‘plan route’ has cured our wonderful street-level blindness; it has nullified so many of those tactical shortcuts and serendipitous discoveries that otherwise allow us to softly subvert the strategies of the urban structure. And when you put it like that, it’s hard not to yearn for a little serendipity.

Projects like Dazed & Confused’s Secret History have sought to address exactly this. By reintroducing the human element into the rigorous landscape of East London, Secret History is one part of the publication’s recent mission to “take stock of how much the area’s creative scene has changed in the last 15 years.”

Spurred into action by the Olympic village that began rising over London’s horizon last year, Secret History is an interactive online map, populated by a selection of “artists, musicians, designers, publishers, movers, shakers, and assorted dreamers” where users plot their personal memories onto the East London map. The aim, according to the site, is to create “a permanent archive that highlights the key moments in the grassroots, underground creative scene(s) that have made the area so exciting.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, the memory map that results is inhabited largely by squat parties, gigs, student halls, lost loves and gallery openings. But then that’s part of the wonder of subverting the objective landscape and injecting a little humanity back into the machine: things become unpredictable, meandering, impermanent, and above all personal.

Secret History is a leading example of how real memories can be used to reshape our environment. Once accessibly documented, they become ethereal way-markers, reminding us of the emotional power of our surroundings. So how do we reawaken this in our everyday travel, rather than just the landscape of past memory (which is what Dazed addresses)? Is it even possible to reinsert such humanity into the living present without recourse to ditching our mobile maps entirely?

A smattering of new mobile services which are taking an alternative look at ‘efficient’ travel might hold one solution. Justin Langlois, artist and Research Director at Broken Labs, is one of the brains behind Drift, a “new app which encourages urban exploration.” Drift guides users through their urban environment using randomly assembled instructions, urging them to engage with objects that would normally remain hidden or unnoticed. For Justin, the project was born of a desire “to explore the possibilities of using smart phones for similar psychogeographic or algorithmic walks; to create a way for users to engage in actively being somewhere rather than just passing through it. ” Drift is a tool, in other words, that gives the pleasure of ‘being lost’ back to its users, allowing them to reclaim their journey as an experience rather than merely something to be endured.Drift is a tool, in other words, that gives the pleasure of ‘being lost’ back to its users, allowing them to reclaim their journey as an experience rather than merely something to be endured.

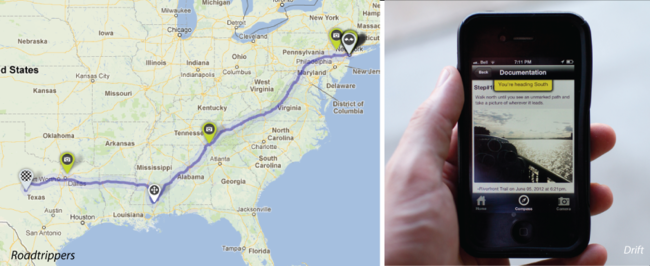

Another approach to disrupting the efficiency of ‘Google Map Syndrome’ lies in two other iPhone apps: Serendipitor and Roadtrippers. Serendipitor offers a service “that helps you find something by looking for something else,” while Roadtrippers has created what its founder, James Fisher, endearingly dubs a “serendipity engine.” For both, users plot their start and end points, then the respective apps algorithmically generate journeys (the former for pedestrians, the latter for US-based drivers) which include a variety of otherwise overlooked interests ranging from abandoned buildings to natural wonders, via the more usual (useful?) array of restaurants, bars and hotels. For Roadtrippers, the emphasis is on a nationwide escape from the beaten track, while for Serendipitor it is more about introducing “small slippages and minor displacements within an otherwise optimized and efficient route.” “I think it’s all too easy to get from one destination to another,” says Drift’s Justin Langlois, “in such a way that you can remove yourself from actively being on that journey. But the more time we spend trying to efficiently get from one place to another in our everyday lives, the more I think we’ll wish for those serendipitous moments when we’re away.”

Perhaps this gentle yearning for serendipity, for accident and chance, is a natural response to the rigours of organisation. And if that’s so, then with the growth on growth of Google Maps and its ubiquitous kith, perhaps it is of ever greater importance that we allow ourselves to remember the benefits of getting a little lost – if only once in a while – rather than always yielding to the siren song of efficiency. With the slight shift afforded by this generation of an urban navigation apps, that’s now somewhat more attainable. If only to a point. But the inherent irony of using technology to interact more with the world around us is hardly a unique one.

“Technology can both help and hinder serendipity,” warns Roadtrippers’ James Fisher. “To help, it can point you in the general direction of what you would find serendipitous, to increase your odds. But there needs to be a moment where you switch off too – an information blackout at the right moment to allow for that serendipity to occur. ” There is an obvious limit , in other words , to how much an app can actual enable us to put our iPhone down and look around us. It can point the way. But it’s up to us to stop and smell the proverbial roses. Or at least notice that they’re there in the first place.