Centreless Culture

With no fixed point of reference, meaning spreads fast and splinters even faster, creating a network of micro-scenes.

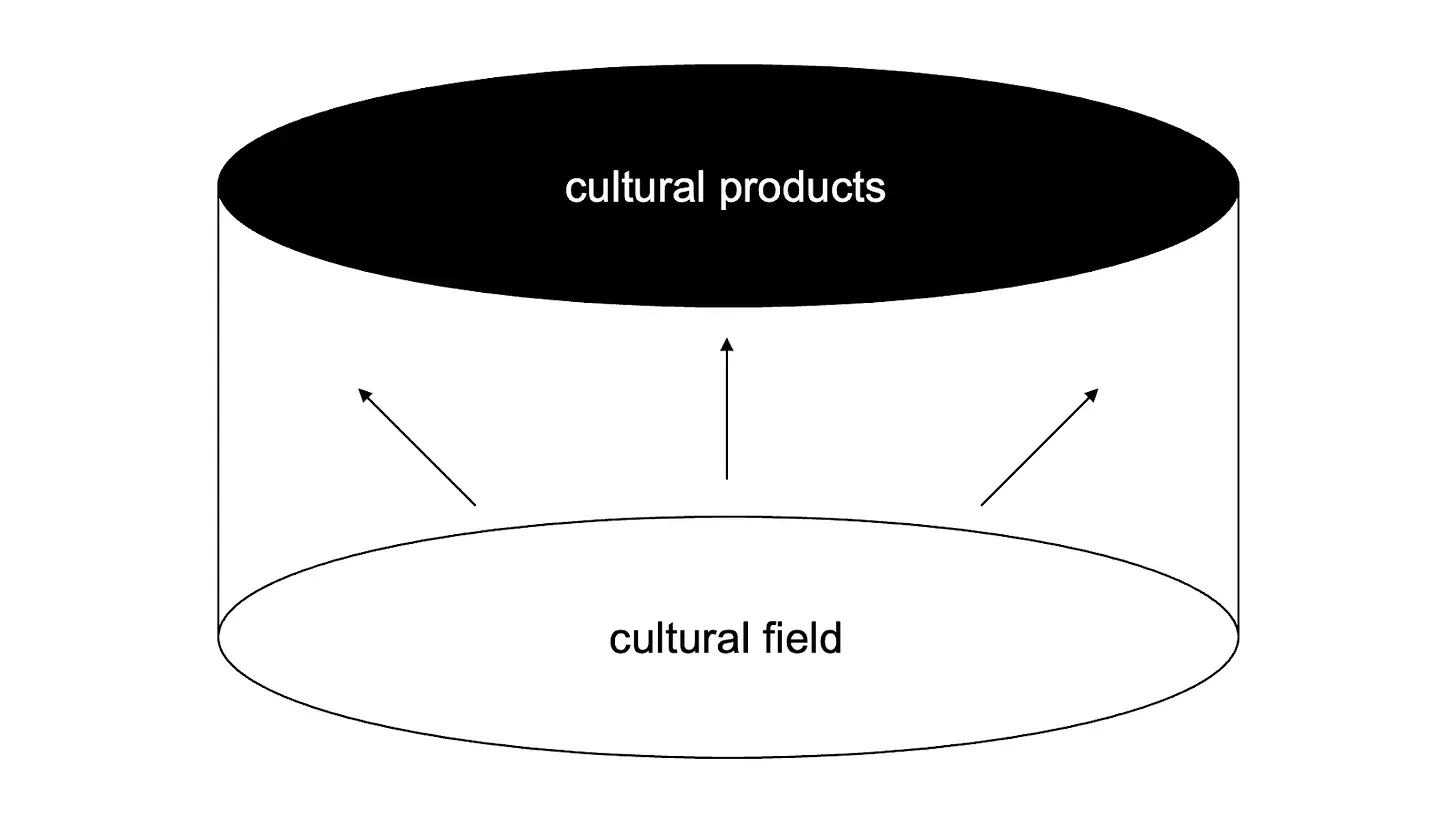

Culture is the set of shared assumptions that organise collective life for a group of people. It’s the background upon which meaning, value and behaviour become coherent.

Culture is also movies, memes, fashion trends, ways of speaking, books, operas, plays and paintings. Cultural products are material expressions of this deeper field that coordinates what’s valued and what’s allowed. Culture is both at once.

It’s like an organism. The field is its DNA, and cultural products are its outward expression. Like an organism, culture also has certain behavioural patterns:

- It always moves from areas of high constraint to areas of low constraint. Over time, culture gets crowded with too many people doing the same thing and it becomes harder to express something new or to gain attention (to get status). People start moving into different ways of expression where norms feel looser and novelty is easier. These new spaces inevitably attract attention and eventually stabilise into new constraints (just as, to any scene, first come the nerds, then come the psychopaths to mine it for profit). This is what drives culture’s eternal cycle.

- Because culture feeds off human attention, what culture is made of will be what captures a lot of it. Because it takes more time and energy to transmit complex ideas, simple ideas spread more easily. So do those that are emotionally resonant or already recognisable (archetypes, for instance, are already path-dependent).

- Certain narratives, visual styles and behaviours recur because they successfully encapsulate a shared feeling or identity that they can also successfully transmit across time. There were goths in the 80s and there are goths today, because the aesthetic still remains a clear way to signal a specific mood and worldview. On a larger timescale, these stable patterns are known as archetypes, with the goth being just one manifestation of the eternal “rebel”.

- Culture is always reconstituting its own boundaries. It redraws distinctions between the sacred and the profane, insider and outsider, elite and common, authentic and inauthentic. Culture mutates as conditions change. It’s a living system constantly reorganising itself.

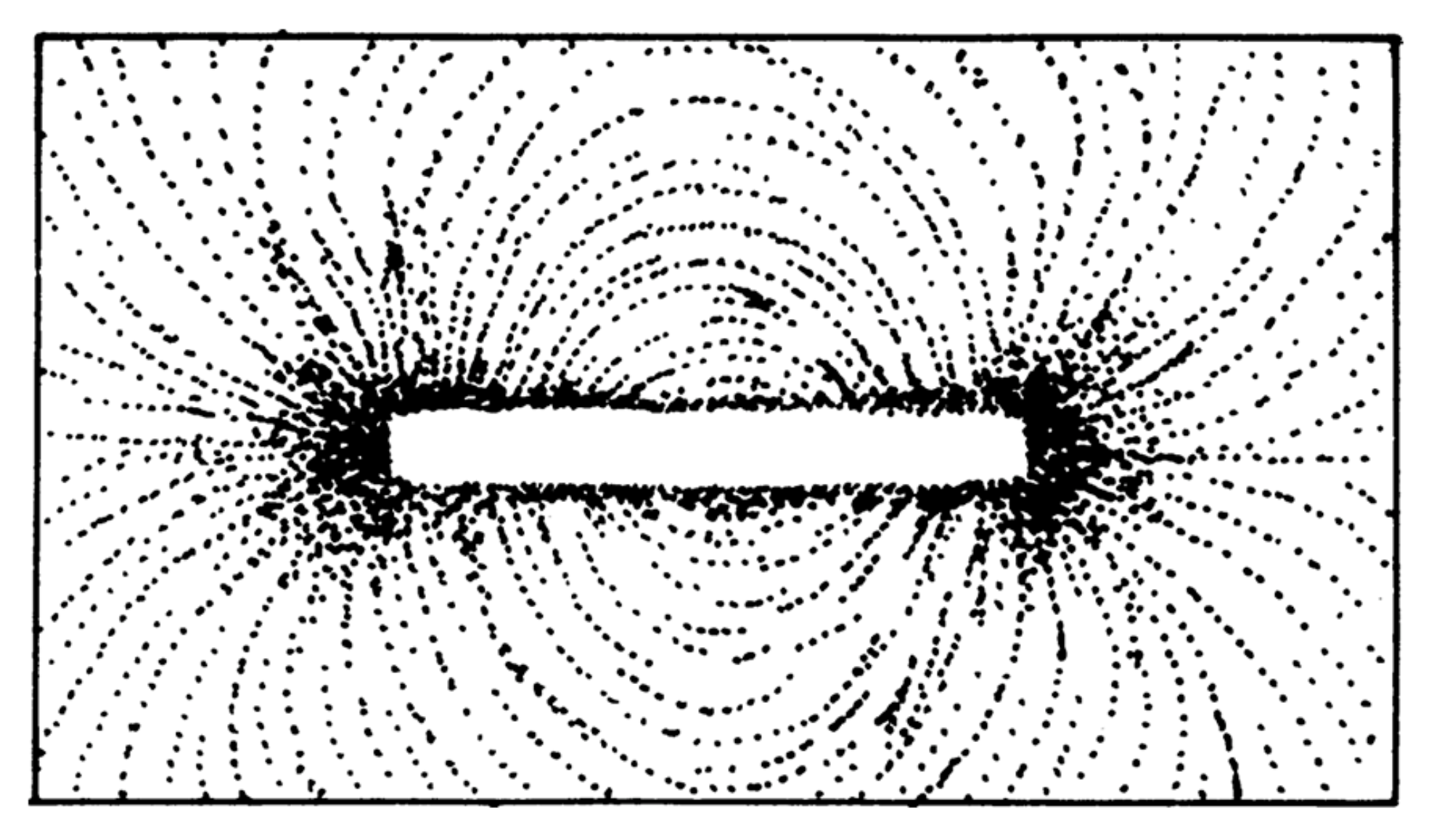

An organism’s environment influences how its natural tendencies are expressed. Culture’s environment is information. This means that whenever the dominant medium of communication changes, so does the way culture manifests.

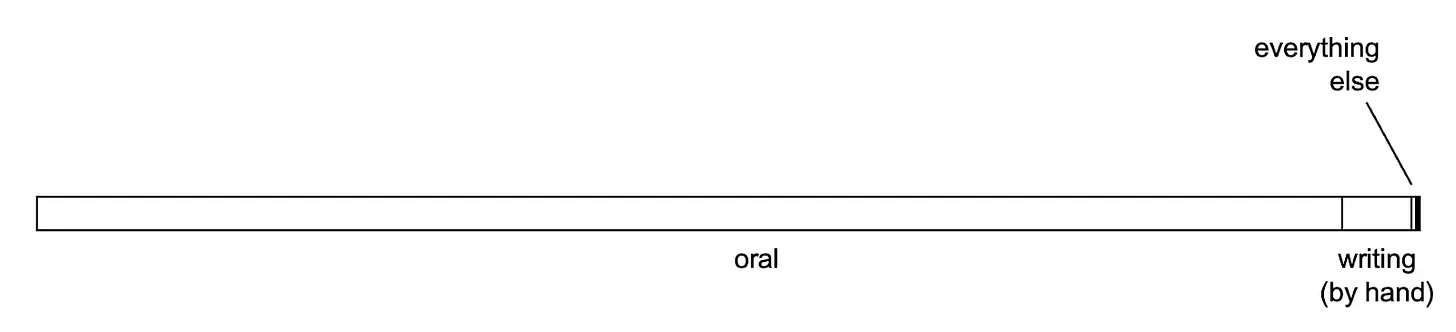

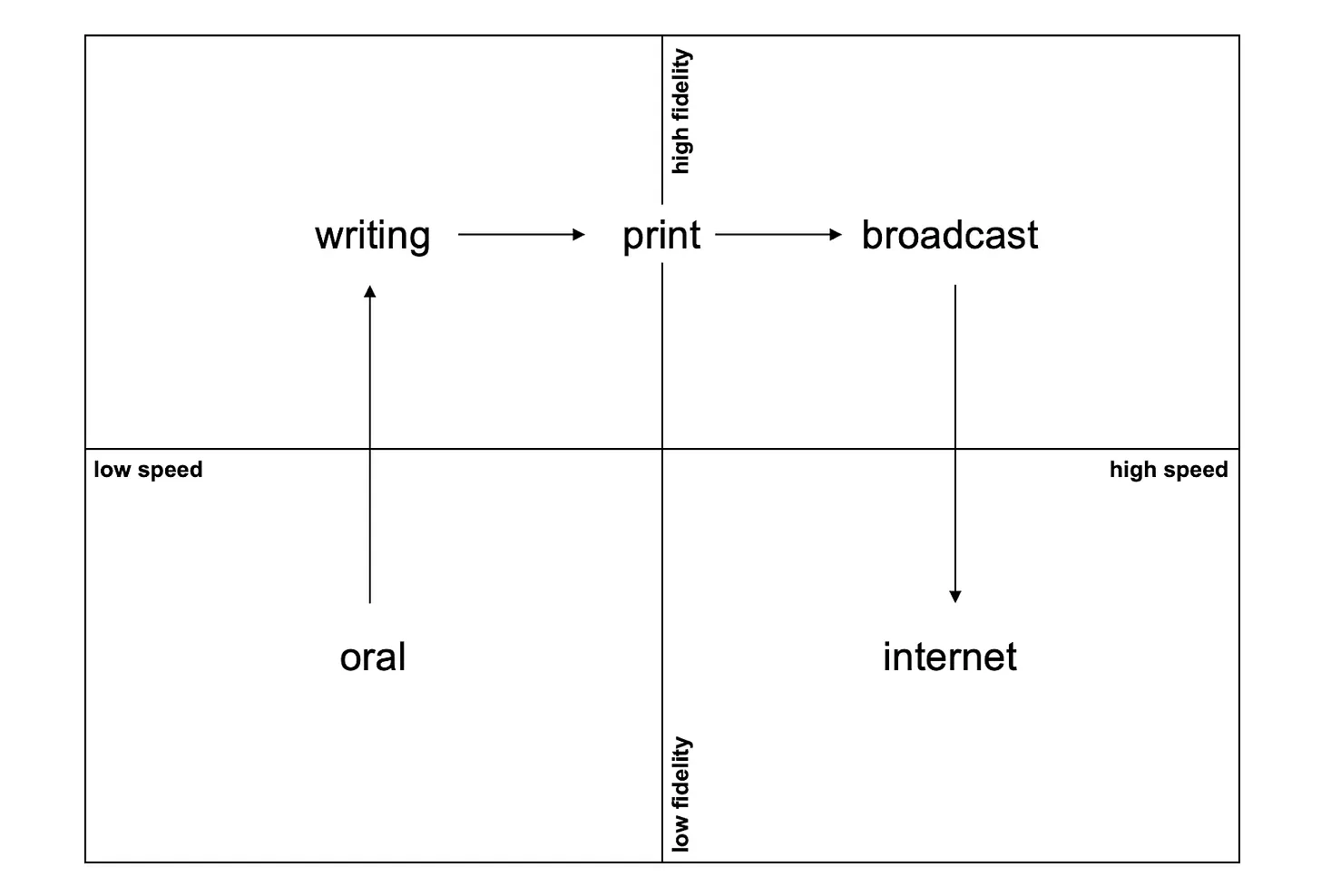

There have only been a few distinct media regimes over the course of human history: oral speech, handwritten script, print, broadcast media and digital networks. Each medium has different characteristics that determine how fast information can travel, how reliably it can be transmitted, how it’s stored, who gets to distribute it, etc.

Oral (dominant for 67,000 yrs)

In the pre-literate era, all of a society’s information lived in memory. Nothing could be recorded for later, so cultural transmission was slow and depended on repetition and collective recall. Because meaning couldn’t travel far across either space or time, culture was highly localised and remained coherent only within small groups. With no formal institutions, culture itself functioned as the system of memory, coordination, cosmology, law, and identity.

Script (dominant for 4,500 years)

Writing introduced the first external storage of cultural information, stabilizing it across time. But because literacy was limited and transmission remained controlled by elites, ideas only circulated narrowly. Culture became more stable and institutional, enabling large-scale identities such as religions and empires, but local variation persisted, since written meaning reached only a small portion of the population. Cultural change remained slow, but it became more deliberate and less prone to drift.

Print (dominant for 500 years)

The printing press enabled high-fidelity duplication and mass distribution of identical texts. For the first time, people across time and place could share the same reference points. Because printed meaning was consistent and widely accessible, culture became more uniform, and this coherence enabled it to function as a coordination layer for geographically vast societies. Cultural change accelerated compared to the script era, but remained stable enough to produce long-lasting forms.

Broadcast (dominant for 100 years)

Radio, film, television, magazines, and newspapers delivered the same high-fidelity content to massive audiences at once. Because only a handful of studios, networks, and publishers decided what reached the public, cultural power became centralised and a “mainstream” formed. People across a country watched the same shows and followed the same bands or movie stars. Cultural change sped up, but it was still shaped by what media institutions chose to produce and promote.

Internet (dominant for 20 years)

When the internet eliminated limits on the replication and distribution of information, it became basically infinite. And when anyone can create content, institutions can no longer have control what gets published (though platforms still influence what gains visibility). Media is delivered to users via personalised recommendation algorithms and audiences to fragment into highly differentiated cohorts. The internet is well on its way to dissolving the centralised mainstream of the broadcast-media era, and replacing it with a decentralised cultural field in which meaning recombines so quickly it cannot even stabilize or integrate into cultural memory.

Each media regime is characterised by differences in transmission speed – how fast information travels – and fidelity – how little of the signal is lost or distorted. The internet is a high speed, low fidelity environment. Memes can spread instantly but also die out quickly. Content is endlessly remixed and recontextualised. High speed, low fidelity environments are particularly turbulent – this is true across any domain, from culture to markets to ecosystems – and produce high variation and continual turnover. In culture’s case, this doesn’t allow for large-scale coherence.

The mainstream erodes as the internet obliterates the conditions required for its existence. Attention is pulled into infinite different directions, and the vast surplus of media production fails to cohere into a unified culture, partially because it’s moving so fast and partially because it’s no longer filtered or canonised by legacy gatekeepers. The entire system becomes overloaded with perspectives and contradictions. Culture enters its fragmentation phase.

But a fragmented cultural system cannot satisfy the human demand for meaning, identity, belonging and status. These drives require stable norms and group boundaries. Under turbulent conditions, meaning, values and behavioural codes can only stabilise in smaller pockets – subcultures – bound by shared interest or identity, where information moves more slowly and members share more common ground.

Even the mainstream separates into dozens of normie subcultures: Marvel culture, Disney Adult culture, NFL culture, wellness culture, suburban parent culture, productivity culture, etc. People craft their identities by mixing-and-matching membership across several of these. Recommendation algorithms only speed up and crystallise this inevitable process driven, more fundamentally, by over-abundant, low-fidelity and high-velocity information.

Under the informatic regime of the digital network, we return to low fidelity conditions, which means that even as information travels far, meaning and value stay close to home. This results in a cultural landscape that most closely resembles that of oral, pre-literate societies – a plurality of local niches that maintain coherence for their immediate communities – but this time, with more interconnection between them.

As Marshall McLuhan wrote in the 60s, electronic media push culture back into an oral mode of transmission, because they produce shared simultaneity, pull people into continuous sensory engagement and dissolve the individualistic boundaries that print culture imposed. In the regime of the digital network, the shape of culture itself is also morphing into something more similar to that of the oral era. In that sense, McLuhan’s “global village” may actually be shaping up to be a web of global villages. Culture takes on the shape of a network.

This essay first appeared on Icognita, Rina Nicolae’s Substack on internet culture.

| SEED | #8373 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 11.12.25 |

| PLANTED BY | RINA NICOLAE |