We sat down with Jamie Brett from the Museum of Youth Culture, which opens soon in London, to talk about the highs, lows and messy brilliance of youth culture. Brett dives into how the museum captures iconic moments alongside overlooked stories – the awkward first gigs, the DIY scenes, the online movements – and how young people themselves get to shape what’s on display.

‘Youth culture’ is a broad and contested term regarding age, mindset and identity. How would you define it in relation to the museum’s mission?

Youth culture has always been there – think back to Plato’s day, when he famously had a little grumble about the local teenagers. Even Professor Mary Beard has reminded us that there was plenty of youth culture in ancient Greece and Rome. The problem is that society hasn’t recognised the impact of young people; they’ve been omitted from the museum taxonomy, and we’re still stuck in a 19th-century view of childhood leading neatly into adulthood.

But something incredible happens in between. We’re not redefining anything – we’re finally acknowledging how young people have shaped society.

Subcultures like punk or rave are an entry point, but we’re also telling more universal stories – of first loves, first gigs, family life – because everyone has a youth culture.

Which past youth cultures or subcultures have been most underrepresented or misunderstood?

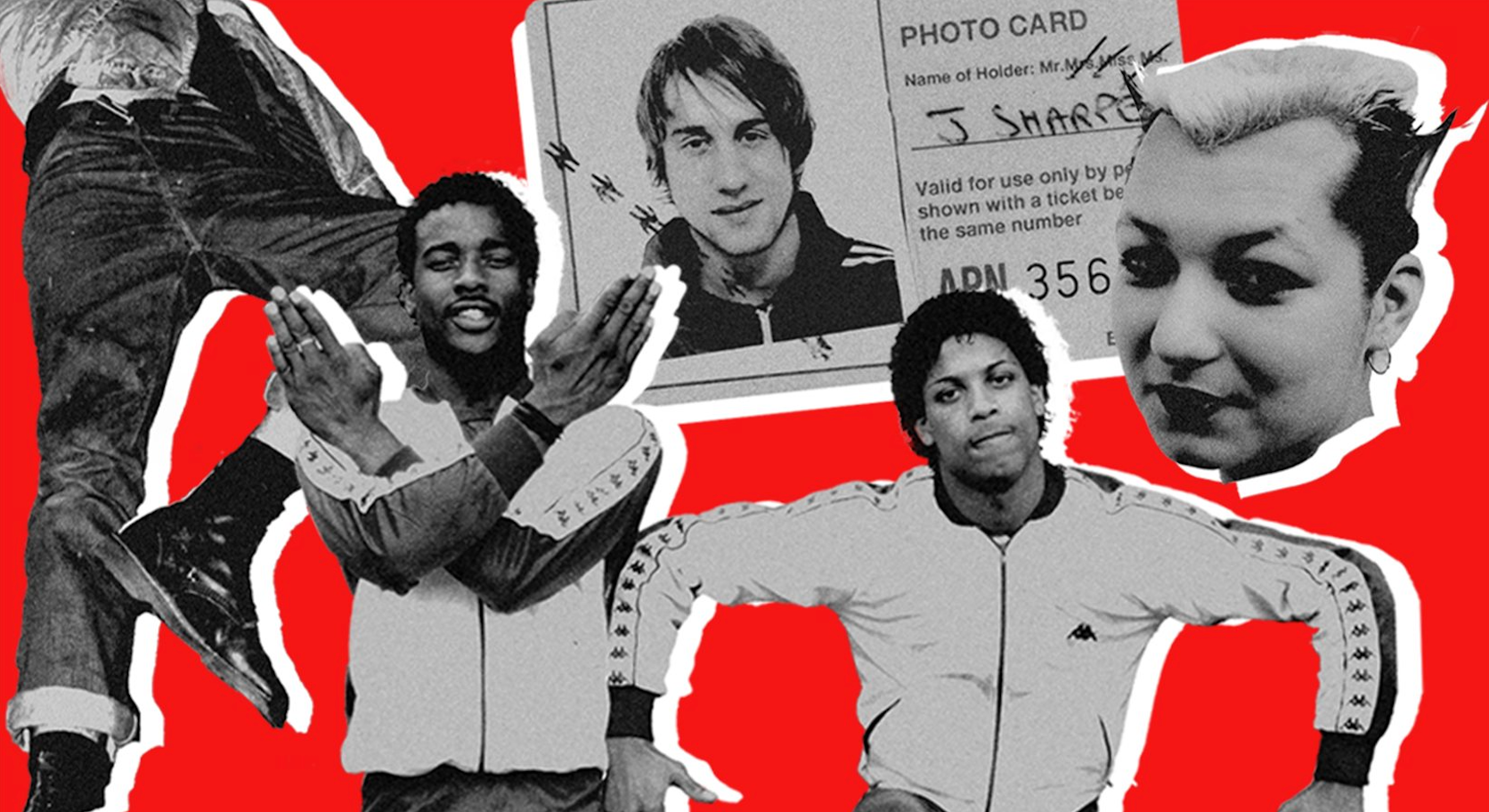

So many scenes have been flattened by unhelpful stereotypes. Especially when there was rarely a camera around to document them, we often end up with just one person’s viewpoint. What we’re trying to do is give ownership back to those scenes and shine a light on quieter or overlooked cultures.

We employ what we call “outreach champions” – people who were actively part of a scene – to help us represent those communities properly and digitise their histories. For example: the South Asian Bhangra scene, LGBTQ+ activism and sound system culture. Working-class life, regional scenes and women’s perspectives are all massively underrepresented in the national youth culture picture.

The Museum of Youth Culture has noted that ‘young people are under attack like never before’. How can the museum help empower young people to reclaim their own stories?

Young people are facing some of the harshest conditions in decades: financial uncertainty, a housing crisis, unstable work and the social challenges of being “forever online” in often hostile spaces. Under this burden, it’s so much harder to live and be independent – no wonder there’s a mental health epidemic.

The museum exists to show them that they belong to a long lineage of young people who have come through difficult times and changed the world through self-expression. Our new space includes a permanent youth gallery – a free space for young people to exhibit – alongside podcast and music production studios and photographic workshop areas. The new museum will also act as a pathway for local youth services to refer young people to, giving them direct access to the museum’s collections.

If you could bottle the energy of one youth movement or subculture and release it back into the world, which would it be?

I think I’d have to bottle the energy of early 1950s rockabilly and the emergence of rock ’n’ roll. It embraced new technologies like television, exporting the idea of the teenager to a global audience and straight to the source. Rock ’n’ roll offered young people a new and exciting life to aspire to after the unimaginable hardships of the Second World War. That energy was revolutionary – it shook society to its core.

John Savage has written fascinating work on the birth of the teenager during this time, and on how the post-war world created a completely new milestone in the human lifespan. Our official museum statement is “young people shape history, shape culture, shape society,” and if it wasn’t for rock ’n’ roll, we wouldn’t be here today!

If today’s teenagers were curating their own exhibit about 2025 youth culture, what do you think they’d include – and what would totally confuse future generations?

The beauty of youth culture today is the infinite resource of the internet, giving people access to photography, art and music. Those days of having to walk to the record shop or trek to a specific store for a scene-specific outfit are over – we simply don’t need them anymore. Young people now have access to a vast array of subcultures and sounds, and they can choose for themselves what they want.

I think young people today are incredibly curatorial in the way they select what they like. It might seem confusing or messy to older generations when you see teenagers with online avatars influenced by anime and manga, while also listening to hyperpop remixes of The Smiths and a drill collective. There’s this remarkable ability to mix and match. Now we’re even seeing a swing toward Gen Z embracing the aesthetics of the Y2K era.

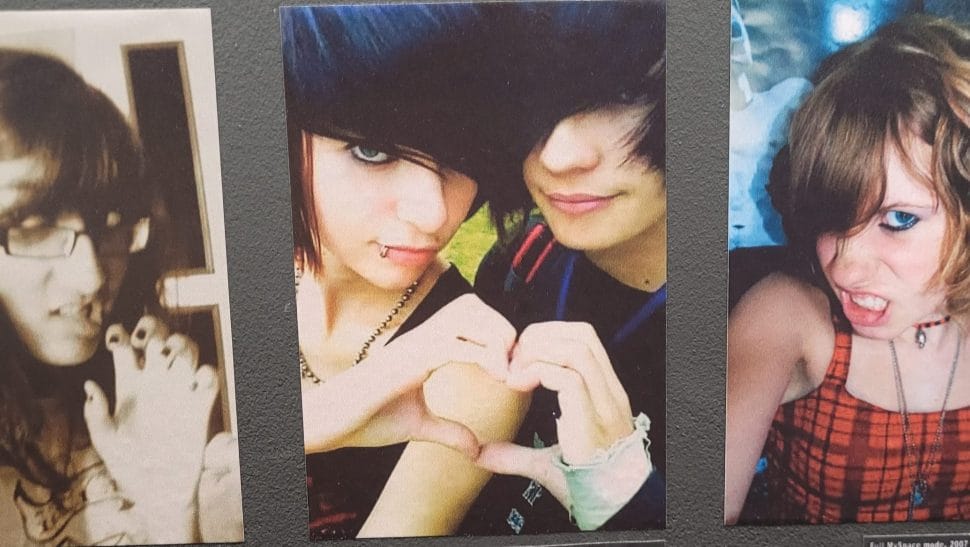

Anthropologist Ted Polhemus coined the term the “supermarket of style” around 2008, interestingly during the height of emo culture. At the time, he didn’t notice emo and argued that subcultures were essentially finished – yet now, young people look back at 2008 and think, “Oh, I wish I’d been part of that scene”. Time provides wisdom and clarity, but generally, older people are just left puzzled by this curated mishmash.

How do you balance the impulse to celebrate youth culture with the need to critically examine its darker or more complex sides – from rebellion and conflict to exclusion and commercialisation?

We always tackle the highs and lows of youth culture scenes head-on. We never shy away from the darker sides of youth culture, and we never delete content that reflects the more challenging aspects of a time period or subculture. Like many museums, we have a digital “red box” to preserve some of the most controversial content we hold. But it has to be there – it has to stay in the archive. We can’t delete history.

We’ve been thinking about this recently as we plan the first major emo retrospective. In that planning, we’ve involved youth mental health charities because we know there were many troubled young people – the world was deeply unsettled, and their futures uncertain post-9/11. We make sure not to foreground darker themes as a major focus of the exhibition itself, but we ensure those elements are discussed. I think people can be inspired by the positivity and creativity that emerged from those scenes, even in the face of struggle.

Your mission emphasises ‘preserving youth culture history and examining inter-generational perspectives on youth experiences’. Could you give some examples?

One of the most moving things we see at our exhibitions is when a parent and their teenager stop at the same photo and realise they’ve shared the same feeling – whether it’s the rush of their first gig or the awkwardness of school uniforms. Youth culture is universal; the aesthetics just change. We consciously design our exhibitions to encourage that dialogue.

In our Grown Up in Britain show, we had submissions from grandparents and grandchildren side by side, both reflecting on friendship, music and freedom. In our new Camden space, we’ll offer intergenerational programming where older photographers or DJs mentor young creatives, and vice versa. It’s about recognising that every generation thinks it invented rebellion, but actually they’re all speaking the same emotional language. When people see that, it softens something and builds empathy across generations – which feels vital right now.

| SEED | #8358 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 16.10.25 |

| PLANTED BY | PROTEIN |

Discussion