Why Typos Are Chic

Brands, take note – in a ChatGPT world, the occasional mistake is a refreshing reminder that real writing can be perfectly imperfect.

In her 2024 song Slim Pickins, Sabrina Carpenter sighs over her lover’s literary shortcomings: “This boy doesn’t even know the difference between there, their, and they are.” Her dry delivery says it all – she’s tired of dating guys who don’t know basic grammar.

It looks like she was on to something. According to a new study from MIT’s Media Lab, we should all be worried about losing our linguistic edge – thanks to AI.

Researchers split participants into three groups and asked each to write SAT-style essays. One group used ChatGPT. Another used Google. The third relied on nothing but their own brains. The ChatGPT users “consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic and behavioural levels.” Meanwhile, the “brain-only” group demonstrated the highest neural connectivity. They were also more engaged, more curious and felt more satisfied with what they’d written.

The dream AI companies like to sell us is that tools like ChatGPT make us faster, smarter and more productive. But this study suggests the opposite: leaning too hard on AI might actually be blunting our brains.

So, as more individuals and brands turn to ChatGPT to compose, correct and smooth over their words, are human-made errors – the typos and the clunky phrasing; all the things we used to dread – becoming more desirable? Maybe they’re not embarrassing anymore. Maybe they’re just … human.

During a panel discussion hosted by Dazed Studio earlier this year, one participant expressed concern that AI is making people question their ability to perform even basic tasks. “I feel like AI is fostering a culture of insecurity,” they said. “I do know how to formulate sentences, I’ve been at school for 15 years, I can write coherently, but I’m starting to lack trust in my own ability.”

In an age hyper-fixated on productivity and optimisation, products like ChatGPT neatly meet the growing demand for fast and convenient outputs. In exchange, we begin to surrender our inherent ability to think for ourselves, turning to the artificial to express our human thoughts – raw feelings, sanitised but grammatically correct.

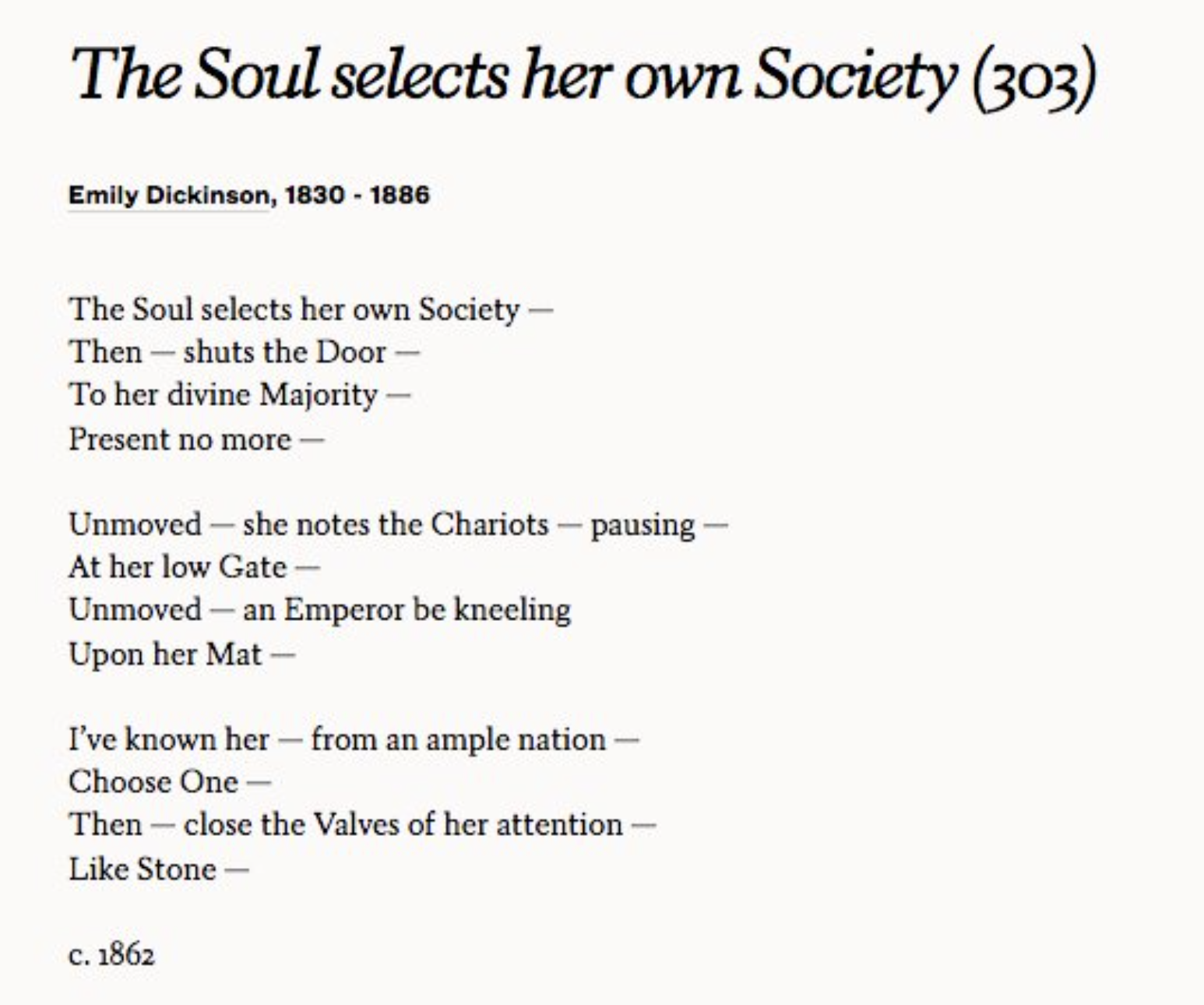

There are telltale signs something has been written by AI. ChatGPT’s prose has a specific tone, rhythm and punctuation style (unless given strong direction). Its voice is confident, sometimes overly so, and while trying hard to sound original, it can veer into the pretentious. It often toys with contrast in an attempt to convey a sense of nuance. It exploits the poor em dash relentlessly.

The em dash has become such a noticeable quirk of ChatGPT-produced writing that its appearance alone can raise suspicion. In the Rolling Stone article “Are Em Dashes Really a Sign of AI Writing?”, Miles Klee notes how “polished” prose is increasingly assumed to be artificially generated.

Questioning the authenticity of someone’s words isn’t new. Rumours of ghostwriters, pseudonyms and miscredited work have long circulated in literary circles. But for the first time, we can’t even be certain the author is human. As a kind of aftershock to this destabilising shift, we now find ourselves knee-deep in a growing mound of self-published newsletters and Substacks.

First, everyone was a DJ; now, everyone’s a writer.

Substack boasts tens of millions of subscribers, including over four million paid subscriptions to publications, 30 of which earn at least $1 million per year, according to its 2024 investor summary. But the sharp rise of bedroom writers hasn’t come without criticism.

The pithiest articulation of this critique naturally comes from satirist and writer Ziwe – best known for her interviews with the likes of George Santos, Anna Delvy and Reneé Rap – who has over 12,000 Substack subscribers. In a post on the platform she shared, “substack is cool but writers do need editors lol”.

Her timely opinion gained significant attention, with replies offering a healthy mix of agreement and pushback. A few weeks later, fashion writer Emma Lou Cogan, who has almost 6,000 Substack subscribers, posted:

“‘don’t start a substack if you don’t have an editor’ kindly <3 STOP <3 i did not come onto substack to start my own personal new york times or write a senior thesis. i came on to be a screaming girl with great taste”.

So what’s the problem with having more writers and more opportunities to share their work? Elijah – a DJ, writer and founder of the record label Butterz – once said, “More people casually DJing is good for music.” If we apply that same logic to writing, then surely a rise in casual writers should lead to a richer, healthier literary landscape.

But Ziwe’s critique carries some weight. Every day across hundreds of Substack feeds, there are floods of reposted pieces accompanied by comments like, “The best thing you’ll read all year”, or “If you’re lost in your 20s, you MUST read this!!!!” Then when you actually read them, they are aggressively mid.

Founded in 2017, Substack began as a platform for individuals, with the goal of enabling writers to publish directly to readers. But, as ever, the corporations have started to creep in, believing that having a presence on the platform will make their brand feel “authentic” and "relevant" (all soon to be DIRTY WORDS).

In many cases, though, Substack has proven to be a compelling way for brands to cultivate a more candid, intimate connection with audiences. This is certainly true of Rare Beauty Secrets, the Substack from Selena Gomez’s beauty line, which describes itself as the “semi-authorised” look behind the scenes of the brand. Posts range from beauty deep dives and product creation explainers to interviews with the Rare Beauty team and curated city guides – the casual nature of the platform cutting through the gloss of social media and enabling a more expansive way to connect with readers.

Hinge also joined Substack recently, launching No Ordinary Love, described as an “anthology of imperfect love stories” from “fresh literary voices,” reflecting an understanding that in an era where AI can generate infinite volumes of content, speaking with intention and a distinct voice is essential to stand out.

Whether she saw it coming or not, Emma Lou Cogan’s irony-laden comment about Substack becoming the next New York Times is edging closer to reality. While The New York Times might not be on Substack just yet, New York Magazine is – though presumably, its readers could just get their fix directly from the printed magazine and website.

Increasingly, brands are cutting editors and content writers from their teams, instead relying on AI – or a single person using AI – to produce large volumes of copy across online platforms and social media. As such, brands with recognisable voices that sound like the result of considered, human thoughts, are dazzling gems within piles of content slop.

Artisan perfume brand Ffern is one of these rarities. The product descriptions read like fairytales, the words clearly coming from someone who knows how it feels to have the sun kiss their skin, watch sunlight dance on the waves and taste freshly plucked fruit.

“It’s early July, and the time for peach harvesting is upon us. In the sun-soaked orchards of Andalusia, southern Spain, our peaches ripen under golden skies, nurtured by well-drained, sandy-clay soils that produce a perfect fruit – rich in colour, with juicy flesh and velvet-soft skin.”

We each speak with one-of-a-kind accents, our speech peppered with little peculiarities that make us uniquely ourselves. Often, the way we speak and write shifts every few months, shaped by what we absorb from others – borrowing words and phrases from all over, piecing together a constantly evolving palette.

The opportunity for instant, flawless writing is now just a few clicks away, making it all the more important to find a voice of our own. Our edge against AI is that no one can express our internal worlds quite like we do – drawn from our personal experiences, references, tastes and intentions. Turning to AI might provide a wad of text in a heartbeat, but its meaning is contrived, and its tone can never match what comes from a living, breathing, messy human being.

| SEED | #8333 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 08.07.25 |

| PLANTED BY | PROTEIN |