The Art of Travel

A mid-Century travel magazine that championed long form writing gets revived for a generation jaded by user reviews and bite-size guides

At the turn of the 20th century, travel literature almost exclusively consisted of patriotic tales of brave, often heavily moustached men who craved adventure. Popular activities included wrestling lions, falling out of planes and climbing Everest. Often written first hand, such pieces portrayed the world beyond Her Majesty’s borders as being wildly dangerous, somewhere that should only be entered with a trusty Winchester rifle firmly in hand.

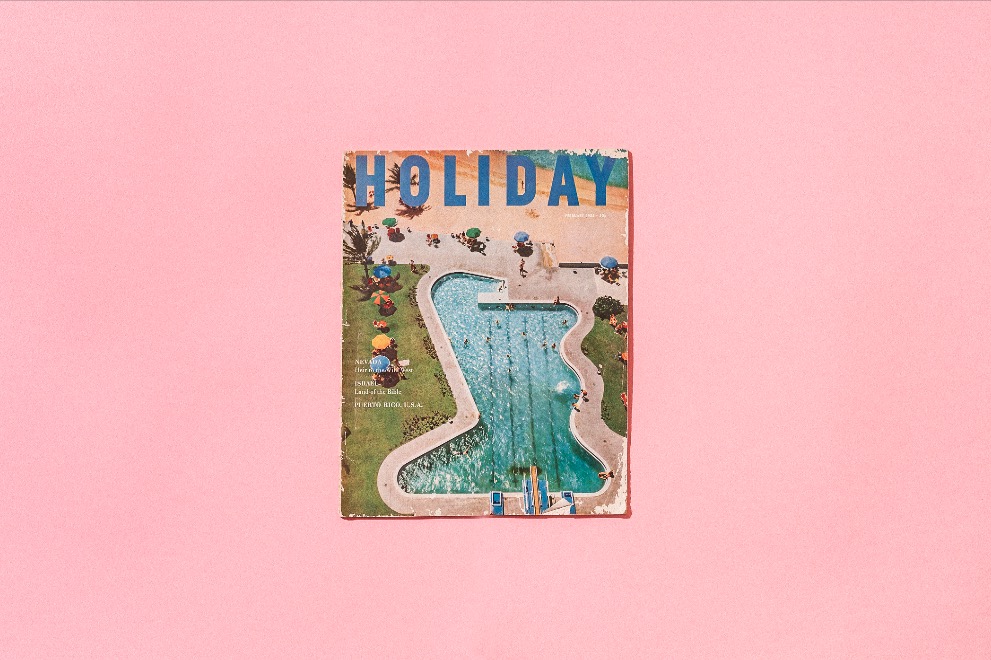

However after the Second World War, masculinity and bravado became less vital to the traveller’s identity; adventurous travel developed a new, more re ned demeanour and it spoke to men and women. This new lifestyle-influenced globetrotting needed branding and it needed spokespeople. Launched in 1946, Holiday magazine embodied the informed traveller, with top-draw colour photography and an unparalleled roster of contributing writers including Jack Kerouac and Ernest Hemingway. The magazine was composed almost entirely of long form travel essays, written from the point of view of the writer without constraints on style, objectiveness or length. The magazine was more than just a guide to where to go and what to eat – it was a reference for politics, culture and ideas.

At the top of its game Holiday had more than one million subscribers. In his book Ten Years of Holiday, which was published in 1956, Clifton Fadiman described the magazine as follows: “Holiday is not an organ of the intellectuals. Holiday is a magazine of civilised entertainment. It aims at satisfying and spurring the leisure-time interests of a sizeable number of moderately well- heeled Americans. It is wedded to no doctrine except that of making propaganda for the politer pleasures of our time.”

In 1977 after a dip in sales and a refusal to compromise on costly contributors, a decision was made to cease publication. Since then, countless travel magazines have been and gone, none managing to fully replicate Holiday’s model. But, after a 37-year hiatus, Holiday has been resurrected as a bi-annual by French creative design studio Atelier Franck Durand. “Our fascination for the magazine and the frustration we felt from not being able to find a contemporary equivalent drove us to revive it,” says Franck Durand. “If we’d launched a new magazine, maybe we wouldn’t have gone for print, but Holiday is first and foremost an object with a specific format, and with the quality of its contributors it can be seen as a luxury good.”

Holiday is not an organ of the intellectuals. Holiday is a magazine of civilised entertainment

Marc Beaugé, who was keen to start his own travel magazine but reluctant given the print landscape, was drafted in as editor-in-chief. He’s con dent of Holiday’s solid foundations:

“I think when you do printed magazines nowadays you need to aim for excellence, you can’t just make average magazines that would have worked maybe 10 or 20 years ago when there wasn’t the internet. Now only the best magazines survive.” Despite the drastic changes in travel and printed media since the magazine’s heyday, Beaugé promises to stay true to Holiday’s values, sticking with novelists rather than journalists and complementing the editorial with the cream of the photography world. For the relaunch, Arthur Dreyfus explored Ibiza while the latest edition focuses on Scotland, with Irvine Welsh representing his native land and Karim Sadli and Josh Olins on photography duty.

These days, travel media has shifted towards online reviews and crowdsourced recommendations, and while these resources may on occasion include informed opinion, Durand and Beaugé believe many people would rather read the long-form travel writings of contemporary literary heroes. Where a large portion of the travel editorial and imagery we consume today can be found on eeting, disposable websites and blogs, a carefully curated body of literature and photography is a welcome blast from the past. The format is timeless and it belongs to Holiday.