Piracy’s Back

How streaming’s failures reawakened digital rebellion – turning piracy from a crime into an act of self-defence.

Back in 2020, when we were all stuck indoors and slowly losing our minds, Teleparty (then Netflix Party) brought us digital relief. It enabled us to sync up shows with our friends, chat along live and pretend that staring at a laptop screen together was the same as hanging out. Netflix was booming, everyone was still sharing passwords freely, and movies – with cinemas shut – were suddenly cheap and everywhere. Streaming was thoughtless and easy.

Fast-forward a few years, and that dream’s gone sour. Streaming feels less like a golden age and more like a long, expensive hangover. Prices are up, quality’s down and content’s scattered across so many platforms that even trying to remember where your favourite show lives can be a struggle. The result is that piracy – the old-school kind – is making a comeback.

Visits to pirate sites have jumped from 130 billion in 2020 to 216 billion in 2024.

At least some of the reasoning is simple: streaming giants have been following the mantra of what internet critics call “enshittification” – the slow, inevitable process where platforms start out good, then become bad, then become unbearable. Yet that’s the plan: to become so locked into our lives that we can’t escape them. Private equity takeovers have loaded studios with debt, forcing them to crank out quick profits. Streaming services are throttling video quality, slapping on more ads and tripling subscription costs. Some UK households are now paying close to £700 a year just to stay legally entertained. It’s no wonder some are drifting back to the open seas for free content and a hit of piracy nostalgia.

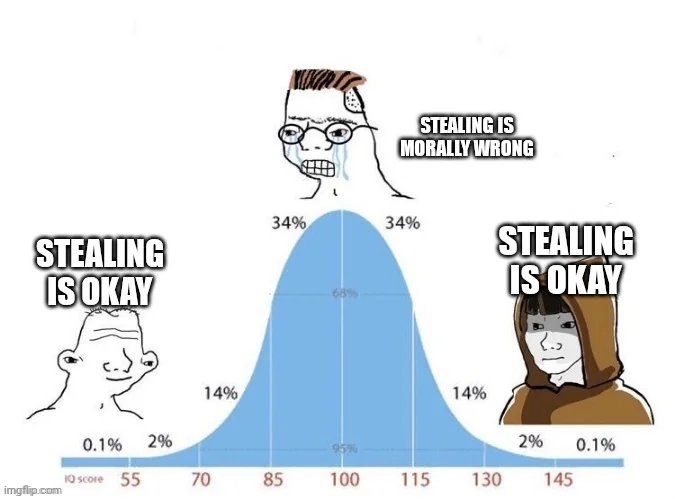

If you’re under 30, chances are you’ve already pirated something. 76% of Gen Z say they have, compared to 67% of millennials – which basically means Gen Z learned from the best. Piracy is a way to say “no thanks” to bloated, over-monetised systems. It’s not even that hard anymore.

In a YouTube video, culture channel GEN compared piracy to the housing crisis. When buying a home is impossible, most people are stuck renting. But with entertainment, if the system’s rigged, you can simply opt out. With piracy, you can always return to illegal content: there’s agency in this.

Gabe Newell, the founder of both Valve, a major video game developer and publisher, and Steam, a platform that turned gaming from a piracy free-for-all into a digital storefront empire, once said that the best way to stop piracy isn’t punishment, but through giving “people a service that’s better than what they’re receiving from the pirates.”

That logic still holds – and audiences are pushing back. Over half of Gen Z have cancelled at least one streaming subscription this year. Across the US, 39% of people have done the same.

The consumer has unusual power to actually move value in these industries, which is exciting. There’s been a surge in searches for Jellyfin, an open-source media server that lets you host and stream your own film and TV library. Think of it like building your own private Netflix, minus the corporate sanitisation and monthly fees. Some users are ditching the clean, Netflixified alternative media server, Plex, for the more DIY, grassroots Jellyfin instead.

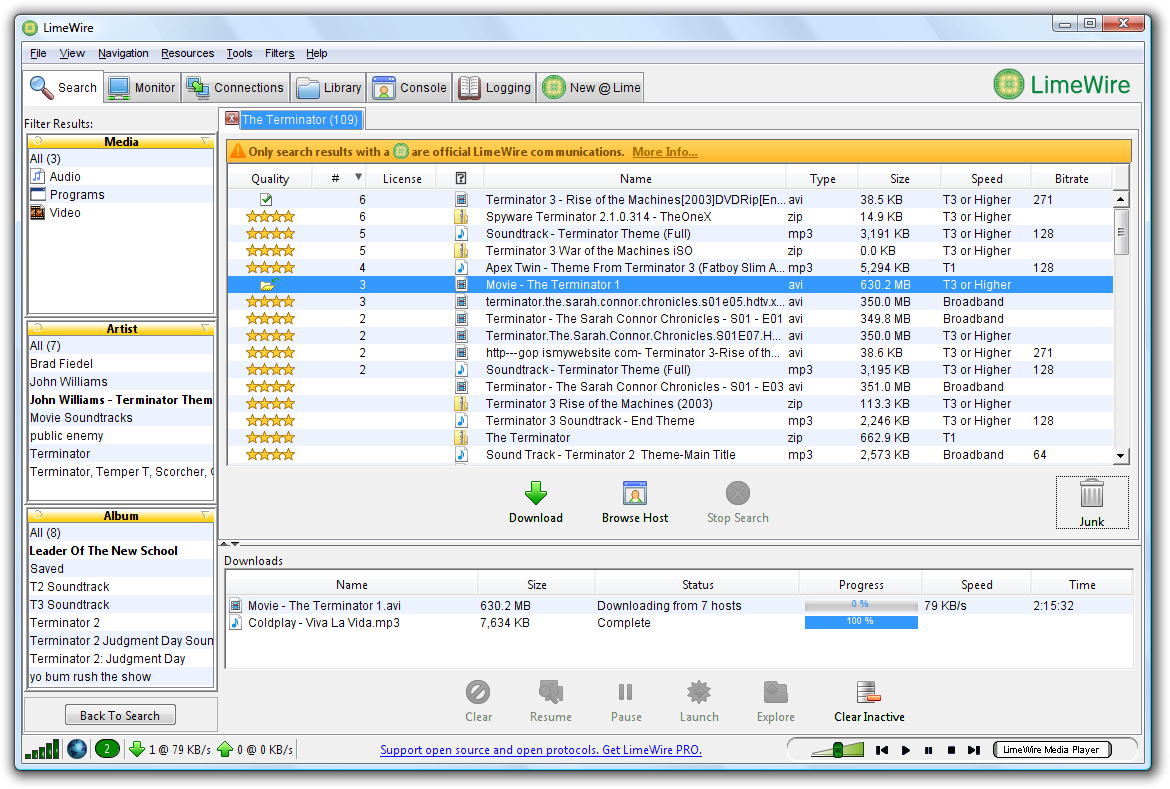

Even the way people access media illegally is shifting. In 2023, almost everyone who pirated was streaming rather than downloading files. But by 2024, it was almost 50/50 again. That’s not just nostalgia – it’s a quiet rebellion. A return to actually owning media, to archiving things before they vanish behind paywalls or disappear from the catalogue. It’s digital tactility: you don’t just watch the file, you keep it.

No wonder we’re seeing weird reboots of LimeWire and Napster, banking on millennial nostalgia for the early internet’s wild west. Today, piracy is less about theft, and more about preservation and control. The fleeting motion of a stream can’t match the grounded media file in a hard drive or a newsletter that will live in your email forever.

This attitude ties into a broader mood online, what some critics have dubbed the “scam or be scammed” era of the internet. It’s the feeling that the internet has turned into a freemium trap: everything’s behind a paywall, everything’s on auto-renew and every platform is trying to quietly charge you for something you didn’t ask for. Being online has become expensive, and the internet knows it.

Yancey Strickler, cofounder of Metalabel, described it perfectly in The Guardian: “I needed to schedule a 90-minute Zoom session but didn’t have a paid account… I signed up for a monthly Pro account, scheduled the meeting, then set a reminder to cancel after. If I didn’t, Zoom would auto-renew me for something I didn’t want.” That simple hack – the “sign up, use, cancel immediately” dance – is basically the middle-class version of pirating.

We’ve all been trained to scheme our way through software dark patterns, fake free trials, and platform subscriptions we don’t need. Piracy, in that context, feels less criminal and more like self-defence.

Between Piracy and Platforms

There’s a reason platforms like Substack, Discord and Patreon are having their (long overdue) moment. They flip the model: small, niche creators, paid directly by fans. According to Components News, 71% of revenue on Substack now goes to writers with under 100,000 subscribers. That’s the opposite of how streaming works, where only the top shows or stars make any money.

People are done chasing algorithms. They want curation, community and a sense that their money is actually going somewhere meaningful.

Paying £5 a month to a writer whose newsletter you love feels totally different than handing it over to Netflix for another season of something you’ll forget next week. There’s cultural weight to it – an identity. Like how subscribing to The Economist used to be a personality trait.

Still, piracy isn’t perfect. It can be lonely. Unless you’re deep in online subcultures or swapping files in Discord servers, it’s often just you and a dodgy torrent file. It’s hard to have a shared experience without systems that help curate or give meaning to the content – it becomes just a hunt.

But maybe that’s the point. Between the corporate sprawl of big streaming and the wild independence of piracy, there’s a middle ground emerging: communities built around shared libraries, curation, and real ownership. Think home servers, Discord film clubs or tight-knit Substack ecosystems – spaces where culture feels communal again, not just consumed.

We probably won’t go back to DVDs on shelves, but the spirit’s the same: taking care of the media you love, trading files, building collections, sharing culture hand-to-hand (or URL-to-URL). The internet started as a place for that.

So, yes, piracy’s back. But it’s not just about stealing movies anymore – it’s about reclaiming agency in an online world that’s made it harder and harder to simply watch what you want. For brands, this shift is both a challenge and a reality check. Audiences aren’t just leaving subscriptions – they’re taking control of their entertainment and choosing where and how they spend their money.

Traditional approaches – pushing content into feeds, relying on algorithms or counting purely on audience attention – aren’t enough anymore. Success now goes to the companies that respect the audience’s agency, offering quality, control and a sense of community; those that don’t risk being ignored or bypassed. Until the platforms figure that out, pirates will continue to sail back out to sea.

| SEED | #8364 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 06.11.25 |

| PLANTED BY | WILLEM DEISINGER |