Choice was once a privilege. Now it’s a trap. What psychologists in the 1970s called “overchoice” has become the baseline of modern life: an endless scroll of products, partners, playlists, posts. Children and young adults in particular aren’t lazy or indifferent – they’re paralysed. Faced with too much of everything, the brain short-circuits. Exhaustion replaces intention. We’re calling it passive attack.

In the 1970 book Future Shock, American futurist Alvin Toffler and his wife Adelaide Farrell argued that the rapid shift into a “super-industrial society” happened so quickly we’ve been unable to adapt. The breakneck pace of technological change leaves people overwhelmed with “shattering stress and disorientation”. Popularising the term “information overload”, they explained how, just as the body cracks under strain, the mind behaves erratically when bombarded with too much information.

Half a century later, the diagnosis still holds – only now it’s intensified. Earlier this year, the Financial Times reported studies showing that reasoning, concentration and problem-solving peaked in the early 2010s and have been in decline ever since.

“This inflection point is noteworthy not only for being similar to performance on tests of intelligence and reasoning”, John Burn-Murdoch suggests in the article, “but because it coincides with another broader development: our changing relationship with information, available constantly online.”

The turning point coincided with a cultural shift: once, information was something we sought out deliberately – in libraries, encyclopaedias or on our early desktop computers. But with the arrival of the iPhone in 2007 and the infinite feeds that followed, information became something pushed at us whether we wanted it or not. According to Burn-Murdoch, we’ve shifted “from self-directed behaviour to passive consumption and constant context-switching.”

This drift into passivity doesn’t stem from laziness, but from exhaustion. The brain, overstimulated by choice, hunts for dopamine quick-fixes to soothe, rather than deep engagement. And in times of cultural turbulence, history shows we often respond by seeking clarity and control. In blitzed 1950s Britain, Brutalist architecture offered a clean, orderly response to the wreckage of war.

In 1980s Detroit, amid industrial decline, the cathartic 4/4 pulse of techno provided release — a sound later embraced by Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall, where underground raves became a force for reconnecting East and West. Each offered structure in chaotic times. Today, as turmoil seeps into every part of life, our coping mechanism seems to be curation — or at least the illusion of control through it.

“Infoxication” – a term coined in the 1990s by sociologist Alfons Cornellà – captures how addictive this glut of content can be. But it’s also sparked a counter-movement. Capsule wardrobes and uniform dressing, both increasingly popular, reduce cognitive load by cutting decision-making out altogether. Google Trends shows searches for “capsule wardrobe” up 60% in the past year, and “uniform” up 42%. Exhausted by the churn of new trends and “cores”, maybe we’re moving towards a more edited existence and rebelling by being basic.

“Normcore”, a term the artist collective K-HOLE came up with in 2013, captured a semi-ironic embrace of “ardently ordinary” clothes. A decade on, the cycle has returned. As SEED CLUB contributor, Gunseli Yalcinkaya wrote in Dazed earlier this year:

“Are people simply embracing their inner basic-ness, or is this an indication of a numbing of our sartorial senses, a symptom of choice paralysis, nostalgia and fashion NPC brain rot?”

For some, it’s radical understatement: The Row’s billion-dollar business proves the appetite for stripped-back luxury. For others, it’s intentional repetition. Steve Jobs wore the same black turtleneck and jeans every day to preserve mental space. Angela Hill, a photographer and co-founder of the cult London book shop IDEA, has her own slightly more liberal approach. As she told W Magazine,

“Every season, I buy a full outfit for every day of the week. I only ever have seven outfits. I like to open my wardrobe and just see everything laid out.”

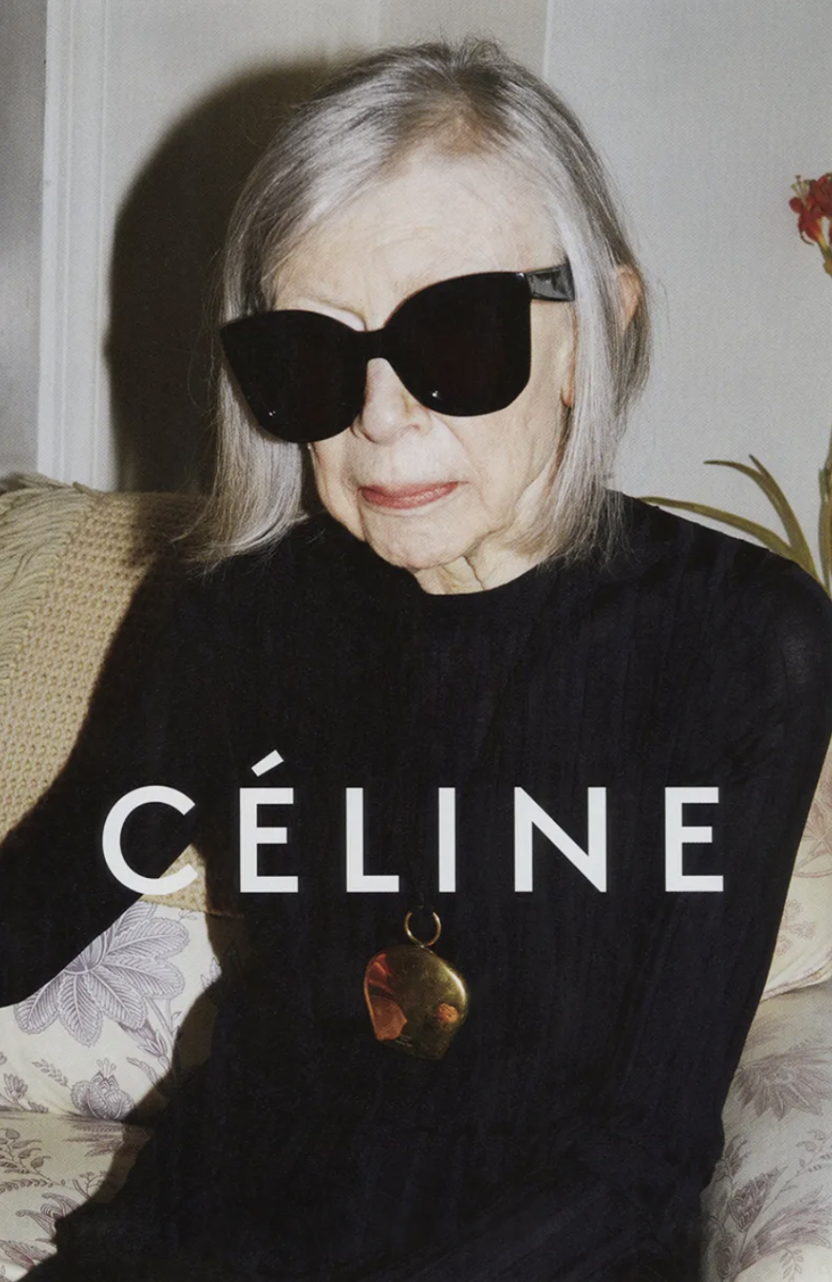

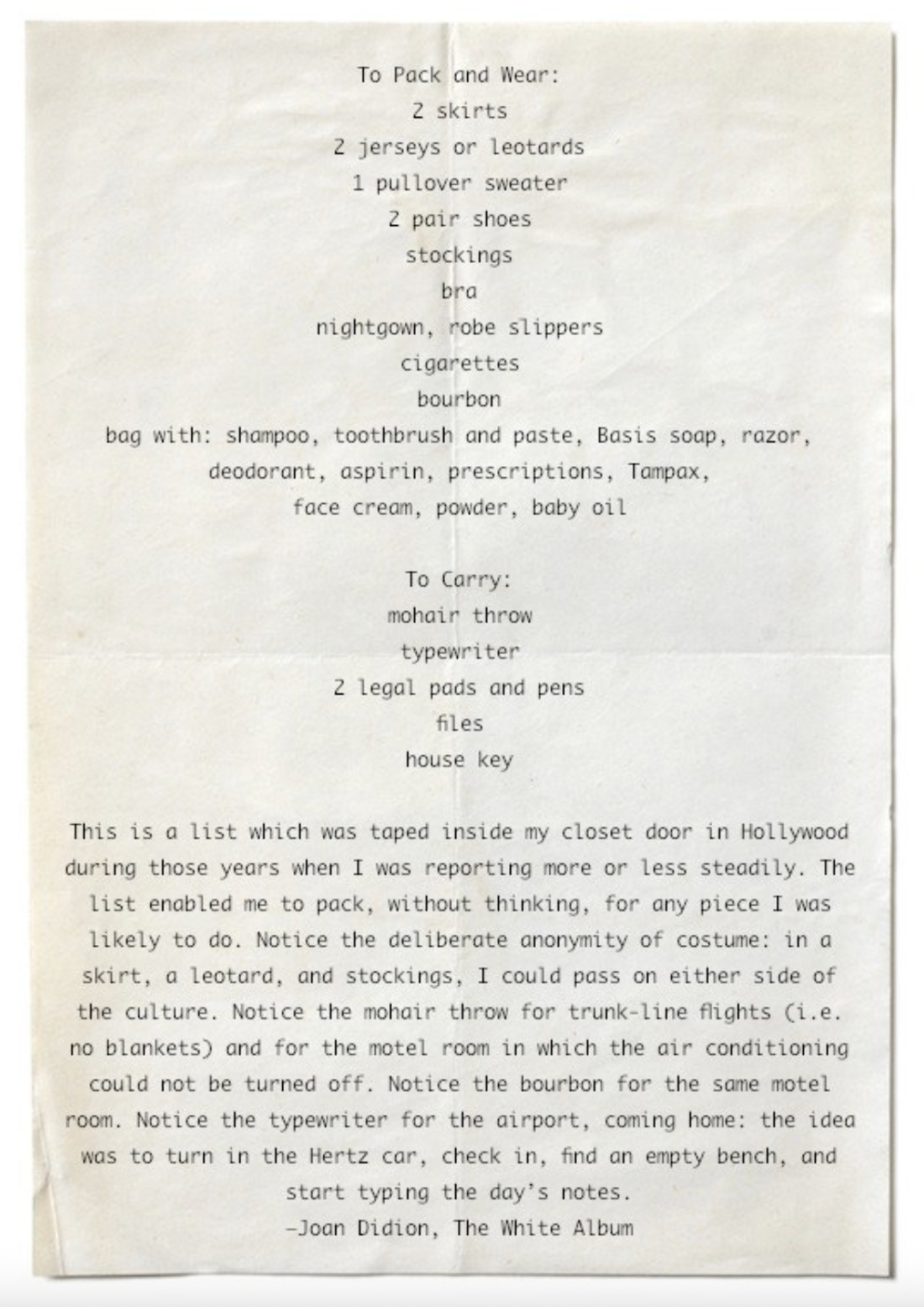

Joan Didion for Céline, Spring 2015; Joan Didion’s packing list – The White Album, 1979

In both cases, simplicity isn’t about being boring – it’s about reclaiming energy and focus. But minimalism is only part of the picture. In parallel, the rise of community influencers shows another way people are coping with decision paralysis. Overwhelmed online, many turn instead to trusted voices IRL: run clubs, book clubs, chess nights.

Groups like Flock Together, a birdwatching collective for people of colour, create belonging through focus and guidance. This year marks the group’s fifth anniversary, and in July, they relaunched Flock Together Academy in partnership with Lego and the Serpentine – a walk and workshop celebrating active engagement through close-knit, physical experiences.

As Sarah Knox observed recently in SEED CLUB, the growing popularity of “community influencer” videos – from street cleaners to public gardeners – suggests a cultural shift away from celebrity worship toward local, purposeful leadership. These figures collapse infinite options into a single, clear invitation: come here and we’ll sort the rest.

We’re tired of casual, meaningless interactions. We want to move with purpose. So what’s the remedy for the influx of information? Clarity, curation and community matter more than endless product drops or opportunistic collaborations. Influence now comes from reducing friction and providing guidance, not from maximising choice. Doing less – but doing it with intention – is perhaps the most powerful move of all.

| SEED | #8346 |

|---|---|

| DATE | 28.08.25 |

| PLANTED BY | PROTEIN |