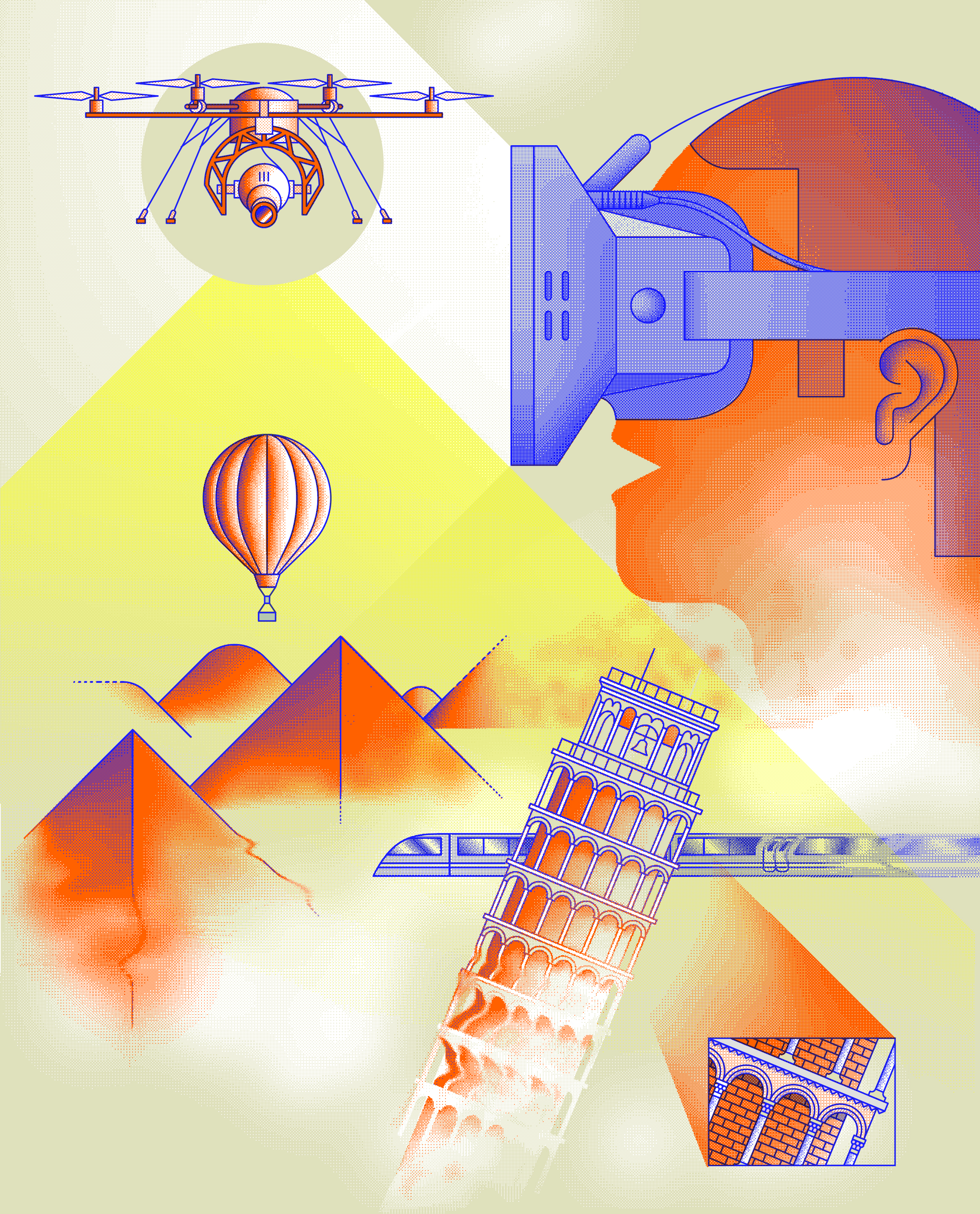

Mind Trip

With home VR headsets just round the corner, we ask: can you explore the world without leaving your house?

Long before we set off for a destination, we arrive there digitally. Walking through the avenues of a new city isn’t so much a new discovery as it is a physical confirmation of Google Street View. Restaurants merely instantiate the menus we’ve already perused on the web. The view from the window of the Trans Siberian Excess is an unedited, uninteractive version of the Google Maps tool. You’ve already heard the noise before, too, by selecting ‘rumble of wheels’ from the drop-down menu.

Digital tools have removed much of the unknown from travelling, for good – you can now look up a hotel’s ‘enviable location’ and wonder who on earth would envy it – and for bad: there are fewer nice surprises. But as we scan and rasterise more of the real world, and develop new, powerful technology for representing it, the gap between the digital and physical is getting smaller. When it becomes so small that we no longer notice the difference, will we become virtual travellers? What happens when online isn’t just a brochure we browse before leaving? What if the destination itself is digital?

On 31 August 1962, Morton Heilig, a New York-based lm director, unveiled the Sensorama. Users would sit in front of the arcade booth-style cabinet, placing their heads inside an upper unit to experience widescreen, 3D images and stereo sound – they would even be tilted in the seat. Its killer app was a virtual travel demo: the viewer rode a motorcycle through Brooklyn, with the wind blowing on their face, the seat vibrating with the revving of the engine, and the smells of New York wafting through. “Its purpose is to enable the user to experience all the sensations of sight, hearing, smell and touch in an unfamiliar environment without actually going there,” said the New York Times, while Heilig called it “the Experience Theatre”.

The Sensorama was an entirely mechanical construction and it pioneered a pre-digital notion of immersive virtual travel. Virtual reality endured various cumbersome iterations in the decades after Heilig’s device, especially in video games, but it never convinced.

Instead, the at, glassy screen came to offer a new type of internet-enabled travel. In the mid-2000s, people started holidaying in Second Life, dealing in Linden dollars at the bureau de change instead of Euros. Companies dedicated to virtual travel sprung up: Synthravels called itself “the rst travel agency for tours in virtual worlds”. Twinity offered “3D mirror worlds based on real people and real cities” – you could go shopping or queue for a bus in a low-res Berlin, say.

The problem was that these virtual worlds were trapped behind glass. And even if you could have slipped, Tron-style, between the physical and digital realms, you certainly wouldn’t actually want to spend any time in the latter: they were like real life, just as imagined by a computer programmer and rendered in bigger pixels. Digital bars and clubs were a particular nightmare. Virtual travel had its rst concierge, but no one called, let alone made a booking. Today, Twinity and Synthravel’s websites are quiet and left alone.

Another route quietly opened up, though. The explosion of cheap, digital cameras – SLRs, smartphones and GoPros – meant that instead of creating shabby virtual worlds from scratch, we started documenting the much more interesting real world in high resolution. Google single handedly mapped it, then started planning on sending its own satellites into space for even more detail (a constellation of 24 by 2018). People geotagged their holiday snaps on Flickr, for everyone to browse – 2.7m user-submitted photos, and counting. The more adventurous/ bigger show-offs strapped a GoPro to their head and climbed the Matterhorn, K2 and Everest, then went canyoning and spelunking. Cameras mounted on drones, used for news programmes, documentaries and sports, have taken us even further, giving us a new aspect on the world.

That’s where we are right now. You can ascend Everest, thanks to an interactive map from GlacierWorks. You can explore TateBritain after it’s shut, thanks to four robots broadcasting as they roam the galleries. A plug-in by ad rm Teehan+Lax for GoogleStreet View turns A-to-B routes into appealing hyperlapses. Sphere, an app, lets people capture “the world in 360 degrees”, then share it with their friends. The Digital Museum, completed last year in Pecica, Romania, lets locals visit any other museum in the world with 3D projections and touchscreens.

The future of all of this lies back with the Sensorama, and in a hack that turns a at screen into truly immersive virtual reality. In 2013, Palmer Luckey realised he could take a 12-cm screen, divide it into two and trick the brain into seeing in 3D. He called it the Rift. “I based it on the idea that the HMD [head-mounted display] creates a rift between the real world and the virtual world,” Luckey posted on a virtual reality forum. “Though I have to admit that it is pretty silly. :)” Luckey took Oculus Rift to Kickstarter, where it raised $2.4m, wowing video games fans with the promise of virtual reality gaming. But games were just one application, as Mark Zuckerberg was quick to realise. In March this year, Facebook bought Oculus Rift – which is still yet to release a consumer product – for $2bn. Zuckerberg wrote in a post to his Facebook page: “Imagine enjoying a courtside seat at a game, studying in a classroom of students and teachers all over the world, or consulting with a doctor face-to-face – just by putting on goggles in your home... By feeling truly present, you can share unbounded spaces and experiences with the people in your life.”

That’s what Oculus Rift and true virtual reality offer: not just a translated version of a real-life experience – another take on it, like sitting down and putting your head inside the Sensorama – but experience, presence, itself.

As Zuckerberg suggested, virtual travel is huge – and a number of start-ups are working to get there rst. Skyscanner, the Edinburgh start-up, has suggested that the Oculus Rift could give holidaymakers the option to try before they buy. Others want to go further than just an advanced technology holiday brochure. One Silicon Valley company is called Jaunt. Where Heilig described his Sensorama as the experience theatre, CEO Jens Christensen calls Jaunt “cinematic VR”. His company aims “to put realism back into the virtual reality experience” and it started when a co-founder, Tom Annau, visited Zion National Park in Utah. “As he went through the pictures on his phone, he became frustrated that there wasn’t a way to truly capture his experience on the at, rectangular screen,” Christensen says. Annau emailed Christensen saying: “Wouldn’t it be amazing if one could combine a high-powered camera with VR goggles to truly capture the beauty of the place and be immersed in it while viewing it? Then I could visit the grandeur of places like Zion any time I wanted.”

By feeling truly present, you can share unbounded spaces and experiences with the people in your life

Jaunt is working on creating the hardware and software to make real places virtual. “We’re in the early days right now, but expect virtual reality – which includes the vertical travel – to ultimately have widespread adoption over the next couple of years as the technology becomes more affordable and more readily available, Christensen says. “There’s been the PC, the web, and mobile and we think cinematic VR will be the next big platform to reach mass adoption.”

Does the advent of virtual travel mean the end of real travel? Almost certainly not. Instead, it’s a supplement. Even the most immersive VR version of Zion National Park won’t beat the real thing – at least not yet. But if you were never intending to visit Zion, travelling there virtually offers a taste. The world opens up to inspection. If a place exists, it will be scanned, and you can visit it.

here’s the argument however, that the real promise of virtual travel is visiting places that don’t exist. Or, rather, no longer exist. One USP for virtual travel is time travel. Take a project like the Venice Time Machine. Created by computer scientist Frederic Kaplan, it is “building a multidimensional model of Venice and its evolution covering a period of more than 1,000 years... kilometres of archives will be digitised, transcribed and indexed setting the base of the largest database ever created on Venetian documents.” Kaplan has said he wants to create a Google Maps and social network of the past. With virtual travel, you could visit the Venice of 1014 via your web browser. (The virtual Venetian rulers might also reclaim the internet doge meme for themselves).

Time travel may perhaps sound fanciful: you’d know it was a set up, not too far from a ‘living history’ medieval village. However, researchers from the University of Barcelona used virtual reality to fool 32 participants in a study into feeling as if they were travelling through the past, and that they were even capable of changing the past. The results were published in Frontiers of Philosophy and Doron Friedman, one of the researchers, told Motherboard that the technique could be applied to immersive virtual worlds like Second Life: “The technology is very complicated and raises a lot of questions; it’s on the border of philosophy.”

Travel itself becomes a rather philosophical question in virtual reality. We speak of movies, video games and books transporting us. When we travel virtually to Dickens’ London, or are shrunk down to the size of a blood cell and navigate the body, can we call that travel, or are those literary and scientific experiences? Does the distinction matter, or will Oculus also create rifts between them? Consider a game like No Man’s Sky. This is a much- anticipated exploration title where a whole universe – up to 18 quintillion planets – is randomly generated. Players explore these realms in a spacecraft; if you visited one planet every second, it would take ve billion years to cross off every one. Will we see the rise of virtual reality explorers, digital Marco Polos bringing back tall tales to entertain us with? Or to use an existing video game example – might virtual travellers tour the servers of Minecraft, visiting the giant blocky structures players have created? A virtual replica of the entirety of Denmark exists. Visiting that sounds like much more fun than the Twinity ideal, of a faithfully rendered real place. (Although small parts of Minecraft Denmark have been blown up by vandals using dynamite hidden in mining carts, and a United States flag erected.)

Both No Man’s Sky and Minecraft are sandbox titles, where players create their own goals, plans and even narratives. They’re about play and curiosity. In that respect, they’re closer to how we travel in the real world. The advent of virtual reality means we will travel to worlds of pure imagination, and experience them as real.