Teenagers’ used to stay up late talking on the phone, pass notes to each other in class and gossip in the loos. But now every bit of new, rumour or event is talked about online via social media.

Nearly all (92%) teenagers aged 13-17 go on the Internet every day, according to the Pew Research Center, and 24% say they are online “almost constantly”. Much of this time is spent on social media, with 71% of teens reporting Facebook as their top social media platform, followed by Instagram and Snapchat.

What these services have in common is their ability to turn real-life experiences into easily sharable content. What’s less clear is how this is will shape young people’s perception of their youth. These precocious social media users are growing up with an ongoing archive of their lives – a comprehensive daily diary of tweets, Facebook posts and Instagrammed photos. But unlike printed photographs and handwritten notes, these records won’t fade. Even seemingly ephemeral exchanges, like a Snapchat photo, can be captured and stored with illicit apps like Snapsave or a simple screenshot.

While there are advantages to keeping the equivalent of a diary online, some worry that an over-reliance on social media could mean that an essential innocence of childhood is being lost. Kids are forced to constantly reckon with their social lives on the internet, worrying about how they present themselves – something that, previously, was only an issue inside the school gates. “When we think of social networking, we have to get over the illusion that we’re actually using it for social connection,” says Niobe Way, professor of applied psychology atNew York University, who has studied children’s relationship with technology for decades. “The way we use it, it’s just for the enhancement of the self.”

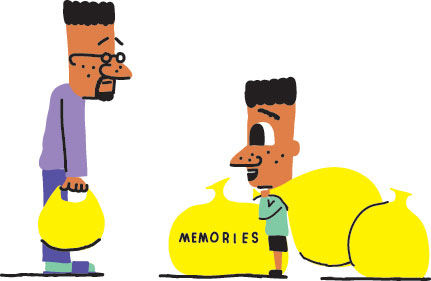

Children and young people look to Facebook comments and Instagram likes for self-validation, and Way worries that technology is forcing children to focus more on themselves than on the friends and experiences around them. “My memory from when I was 10 is climbing a tree with my friend Michelle, and I almost fell down from the tree. I fear my daughter’s memories will be about when she posted this or that online.” Way recounts a moment when her daughter “came down to me screaming with delight” when a favourite band followed her on Instagram.

There's a shift from social memory to self-memory. You're not going to remember who you were with when you posted something online

It seems that, as younger users spend ever-more time online with the help of omnipresent mobile devices, childhood will be made from virtual moments like these rather than of recollections of physical events, such as riding a bike or sneaking off with friends for an illicit adventure. “There’s a shift from social memory to self-memory,” says Way. “You’re not going to remember who you were with when you posted something online.”

However, other experts disagree. Nathan Jurgenson, a social media theorist and researcher for Snapchat, has identified the “digital dualism” attitude. According to Jurgenson, this is the misguided perception that experiences on the internet are less important or more disconnected than activities in the physical world. Jurgenson’s view is that memories of social media are just as legitimate as more traditional recollections about climbing trees.

It’s easy to critique a culture of apparent narcissism, but social media will also help rekindle pleasant memories that might shape our adult lives. Molly Knefel is a writer and an after-school teacher in Brooklyn who has observed the effect of social media on her students. “It’s so much easier for kids to document their lives on social media, in a blog, on Facebook, or in a video,” she says. Looking back at records left on social media could give us glimpses into our earlier selves as we mature. “There’s something good about the idea of having to be reminded that, when you were 13, you were really idealistic, really funny,” Knefel argues. “There will be a record of some of the things people cared about and were passionate about, so it’s not so easy to forget.”

Knefel hopes that an early interest in saving the environment, for example, or an obsession with reading or writing, could be rekindled by looking back through social media archives. “I think adulthood would be better off if it were forced to reckon with youth more sincerely and more honestly,” she says.

Studies show that humans don’t, in general, recall much from childhood. “From the ages of three to seven years, adults have fewer memories than would be expected, based on forgetting alone,” a report from the American Psychological Association found. Usually, our brains selectively erase, emphasising happier memories over day-to-day activities. Social media records might bring these lost details to light.

While kids might cling to their phones rather than chat in person, that doesn’t mean they’re not developing lasting connections with each other. It’s just happening in a different way. The early internet, according to some theories, helped people to develop close relationships, through chat rooms, for example. “We got along better in these deep textual relationships than we tended to in real life,” recalls Douglas Rushkoff, the author of Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now. Today’s teenagers are using Snapchat exchanges and Instagram comment threads to build the same digital intimacy.

The fear that social media is destroying childhood also overlooks the fact that childhood has always been edited and augmented by an outside source – parents. “When parents take photos they’re going to post them on their Facebook and they want their family to look cute. They’re not going to keep the awkward pictures; those get deleted,” Way points out. “Such actions change representations of ourselves in childhood.”

Parents control our experiences of childhood, including our social media lives, until we become mature enough to take responsibility for deciding who we’re going to be, both online and offline. Today’s children, who are growing up with social media and who are competent users of a wide range of platforms, will pioneer new forms of communication that are as valid as any that have come before.

Illustrations by Thomas Slater