Fun About Town

City planners are turning up the fun with audaciously imaginative attempts to improve urban environments and promote civic engagement

City planners are turning up the fun with audaciously imaginative attempts to improve urban environments and promote civic engagement.

Earlier this year thousands of people congregated on Park Street, one of the main thoroughfares in the city of Bristol in the UK. The event wasn’t the typical British flag-waving-and-bunting affair: they gathered to witness people hurtle face-first down a 95-metre waterslide. The Park and Slide project, which appeared overnight and remained for one day only, totally changed the character of this public space and imprinted an unforgettable image onto the collective memory.

Park and Slide was the brainchild of multidisciplinary artist Luke Jerram, who raised funds via Spacehive, a crowdfunding website for urban-based projects, to see his idea become a reality. Bristolians could enter a raffle to win tickets to ride the slide, and those lucky few became part of a larger artistic statement: by participating, these aquatic tobogganers were turned into performers, and a living centrepiece of the city.

Jerram is far from alone in his thinking. Many other projects in cities around the world are injecting moments of play into their built-up environments. The Rotten Apple project in New York, for instance, sees street furniture re-appropriated to make functional new items, such as a public chess game made from a piece of wood and chess pieces attached to a fire hydrant. At this year’s Milan Design Week, designers Claudia Dolbniak and Silvia Saure presented Beatspot, a whimsical project that allows passers-by to “play” a musical bench simply by sitting on it.

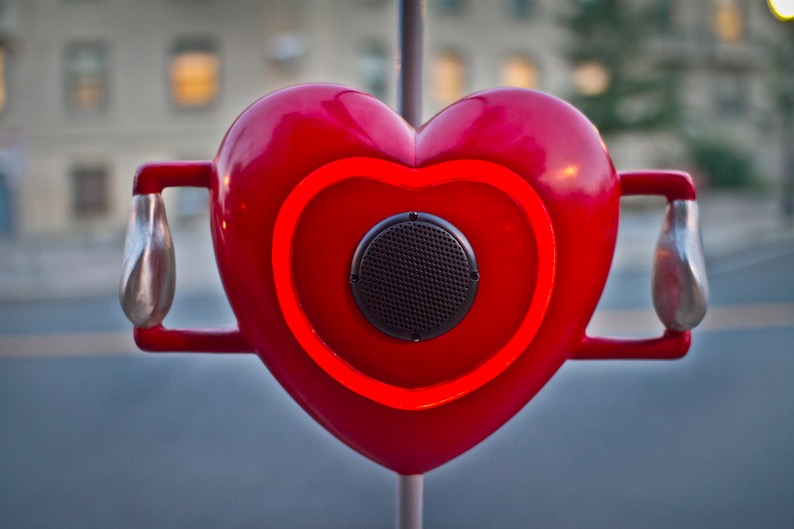

In Boston, Pulse of the City by George Zisiadis invites people to hold heart-shaped devices which convert their heartbeats into a grand symphony of public music. “In cities there’s so much happening around us, that it’s easy to lose track of what’s happening within us,” explains Zisiadis. “Amidst the chaotic rhythms of the city, I wanted to help pedestrians playfully reconnect with the rhythm of their bodies.”

While these projects may seem like the basic ingredients of a fun experience – and charging down your high street on a water slide certainly does sound exciting, especially on a warm afternoon – there is, however, a serious side to these playful designs. Play is a crucial, often overlooked, component of city life. It can combat some of the day-to-day social problems that our urban environment causes. “City life is well-known for being anxiety-inducing and at times overwhelming,” says Francesca Perry, who runs Thinking City, a platform that encourages positive social impact through urban change.“Even a century ago, German philosopher Georg Simmel expressed his belief that the metropolis, with its excess of work and people, caused citizens to shut down and become cold and rational beings.”

And it seems that this rationalisation could be causing us to be lonelier, anti-social and no longer neighbourly. A report by the Grattan Institute think tank in Melbourne claims that one in 10 Australians feel they can’t call on their neighbours for help, while a BBC survey found that a quarter of Londoners say they feel lonely either often or all of the time, with a third stating they don’t know their neighbours – up to 33% of respondents reported little or no sense of community at all. Other studies show loneliness is not just a misery-maker, it can affect life expectancy, with the elderly or vulnerable being especially at risk.

A city’s greatest asset is its people, and play presents the opportunity for us to come together and engage in positive experiences that can build relationships >

The act of playing, says Perry, however micro-sized or localised,can offer a solution to all this. By experiencing play as a group, urban dwellers can create important social bonds with each other. “Togetherness is key,” she explains. “A city’s greatest asset is its people, and play presents the opportunity for us to come together and engage in positive experiences that can build relationships – or, at the very least, provide some much-needed fun.”

Clare Reddington, director of iShed and the Pervasive MediaStudio, part of the Watershed cultural platform in Bristol, agrees. “The one thing that comes up time and time again is this concern about being isolated in a city, and this desire to feel a sense of community,” she says. Reddington is involved in Watershed’s Playable City Award, another Bristol-based initiative, which tasks itself with promoting playful urban initiatives. Its inaugural event last year saw artists and creative types from around the world build technological projects to help people interact with their urban environment.

The Hello LampPost entry, for example, saw special codes being placed on street furniture around Bristol, including lamp posts, post boxes, telegraph poles and bus stops. The idea was to turn the surroundings into a one-size-fits-all chat platform anyone could join, encouraging community debate and togetherness – all that was required was an SMS-capable phone. A message sent to any of these objects was communicated across the entire network, leading to thousands of participants using their city to talk about their city.

While conversations about technology and the city often lead to musings about “smart cities”, a futuristic grand vision where data is used to make the running of a city much more efficient, the PlayableCity Award, with fun interaction at the core of its agenda, does much more. It’s all about getting people together and encouraging them to interact and care about certain aspects of their city, explains Reddington. “The sense of community that play enables can help you make connections with people you don’t know,” she explains.“And it gives you permission to act differently in the city, to break the patterns of the city, and inspires a stronger sense of ownership.”

Ben Barker of PAN Studio, who collaborated on the Hello Lamp Post project, believes it’s essential that informal, unstructured play is democratic and open to all. “We should be seeking to create public spaces that are flexible and acknowledge that different groups and generations play in different ways,” he says. “Having the courage not to formalise or define where certain activities have to happen helps create a playful mentality, and that is powerful.”

There may be good reason for these civic projects to happen now. While there is clearly a will among designers – and even some councils – to experiment with playful urban interaction, play in the city is actually under threat in some locations. The Southbank skate park in London, a place of civic leisure that emerged naturally and is now under threat of closure, is a well-known case. More worrying still, people seeking to reappropriate spaces for enjoyment are being actively discouraged. This sometimes involves “defensive architecture” – features found on publicly accessible structures which prevent them being used for purposes for which they were not intended, such as skateboarding.

So what can be done about this? “We’re at a stage of relying on public/private partnerships to keep the city moving,” Francesca Perry explains. “There’s always a big debate about regeneration of spaces.It’s difficult and it’s about prioritising – my belief is that what needs to lead the creation of these projects is the social impact. Bringing people together is critical to keeping our cities alive and connected.”

There are already examples of play being incorporated into civic spaces on a larger scale, says Perry – you just need to look out for them. “The new Queen Elizabeth Park at the Olympic site [in London] has created a very playful landscape, and I think that reflects this increased attention given to play in the city and playable spaces.” Celebrated planner and urban theorist William H Whyte suggested over half a century ago that what attracts people the most is other people. That is perhaps what’s most appealing about the artistic interventions which interrupt the regular rhythm of our cities. They act as gentle, playful reminders that we inhabit these places together, and allow us to reconnect with one another. We can only hope that future city officials will use a little imagination and consider public space in this light.