Forgoing Conclusions

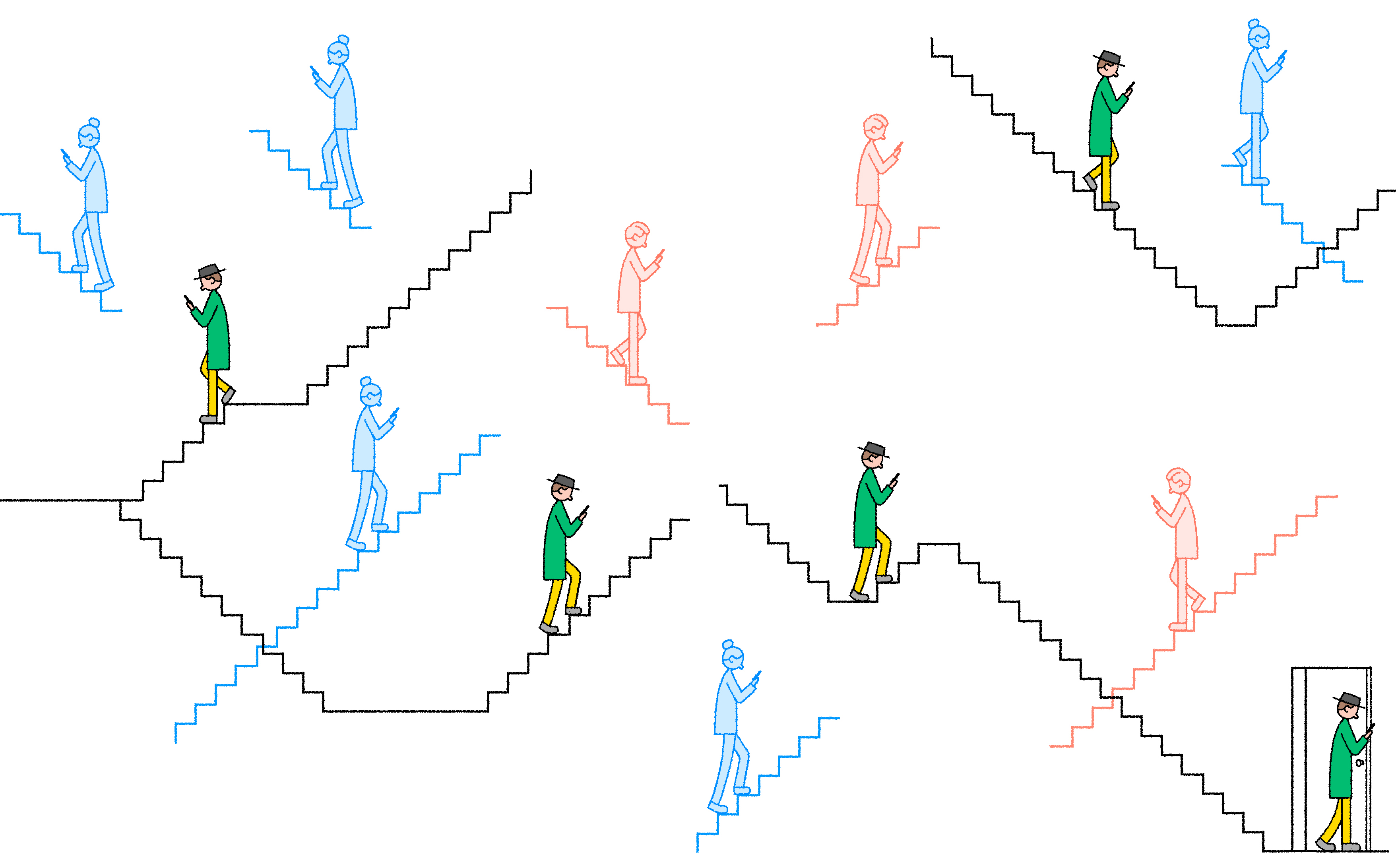

The unfinishable nature of the internet can sometimes be overwhelming, but is the age of never ending content coming to an end?

When you read an article in Time Magazine, the final full stop is embossed with the magazine’s logo. It’s called an end sign, a little nod that you’ve completed the piece you’re reading. Well done, you. When you read an article on the Time website, there’s no end sign. Instead, as you scroll to the last few lines, a second article readies itself at the bottom of the page. You seamlessly scroll from one article to the next, unaware the URL has changed.

Different brands do this in different ways – SoundCloud and YouTube have automatic playlists that never stop, algorithmically side-stepping from song or video until you end up listening to a two-hour mash up of the year’s Pitbull songs without understanding how you got there.

Music and fashion websites like Dazed Digital and Boiler Room tend to employ an endless scroll homepage, so the content doesn’t stop. This bottomless refill means you can stay on the site for hours without ever feeling as though you’ve completed it. It is overwhelming, but it’s not about fighting it, it’s about finding what’s interesting – and giving that credence over stuff that isn’t productive.

“One of the reasons it feels like there’s so much is that smart content creators have realised that certain topics will perform well on SEO or on socials, which they need for traffic and revenue,” explains Stephen Abbott, former producer at the Guardian and now head of the UK Parliament’s digital department.

“So instead of one person writing the definitive article on a topic, everyone will write about the same thing.” Instead of a newspaper, which is designed to give an appropriate amount of depth on each issue it covers, you have 29 different versions of the same old nonsense.

The lack of an end sign is most apparent on social media. Twitter and Facebook have become impossibly busy, but offer little advice on how to read the best content and ignore the dross. Not only do both sites allow you to scroll endlessly, but each time you refresh the page you’re greeted with an entirely different site to the one you just saw. Not only does social media have no end, it also has no start. It’s just a pipe for the flow of content.

All of this was all supposed to make us feel more aware, a breaking news ticker writ large throughout our lives, but for many this endless feed has become a burden. The dream of an internet where content is predominantly streamed has been abandoned: people have given up on RSS feeds, and Google has given up on Google Reader. The old way of using the net to swim upstream in a river of content is disappearing. Instead we’re looking for that feeling of satisfaction that comes with finishing a book or a long article – a digital end sign, a happy ending.

“Each day I wake up and look through so many stories. I probably pick up on about 200 a day, all from Twitter, RSS feeds, lots of bookmarks,” remarks Sophie Wilkinson, news editor of The Debrief, a website published by Bauer and targeted at young women. “It is overwhelming, but it’s not about fighting it, it’s about finding what’s interesting – and giving that credence over stuff that isn’t productive.”

Increasingly, we’re seeing online brands moving back to print or other formats, to create timely, readable content that isn’t delivered in pieces or endless updates. When Abbott was at the Guardian, he was involved a new project, the Long Good Read, which reverted back to a traditional beginning-middle-end story structure. “The idea was to use all the metrics the Guardian had access to – about how long people were reading something, how engaged they were with it – to create a platform where people could see our best journalism. We’d have a story for the commute to work and a story for the commute home. It was limited and effective – at one point we even ran a physical paper based on our algorithms.”

The Long Good Read was a promising but relatively short lived beta project that has now ended. But the tech giants are already working on similar, more ambitious endeavours. Facebook has launched Paper, an app that streamlines your news and social media into an old fashioned format. Another site, Medium, home to long-form journalism, is proving popular. The site is still in its early stages, unclear whether it’s an editorially commissioned site or a platform for user generated content; at the moment it’s a combination of the two. Certainly, it’s the opposite of its creators’ biggest venture, Twitter. Instead of endless short updates, Medium has well designed, curated long-form content. Only a few articles are up-loaded each day, so it’s easy to keep on top of.

Increasingly, we’re seeing online brands moving back to print or other formats, to create timely, readable content that isn’t delivered in pieces or endless updates. The Pitchfork music site has launched a quarterly journal, with more in depth event journalism than it offers online. At $20 an issue, it’s not cheap – but for many that’s a price they’re willing to pay to be assured of top quality content they know they can finish. Pause, a new online music quarterly, is only available as an iPad magazine. It takes the best music writing from across the biggest music sites and repacks it in a magazine format. Its name was chosen because its founders felt that there was such an endless stream of music content that few people ever stopped to read it.

Mobile magazine Offline aims to cut through this noise. It publishes just five easy-to-read articles every month on culture, comedy and design. Each is accompanied by a time which states how long it should take to read. Even traditional news websites such as Slate have started putting the time it takes to read an article in the head-line: surely the most obvious sign that the web is responding to users desire to know when something is going to finish.

Offline’s co-founder Thomas Smith says that our inherent desire to remain informed online will mean it is unlikely we’ll completely disconnect from social content.

“People want to stay informed and feel connected to the world and the people in their lives,” he says, but he does concede that the growing amounts of information will require a better system of delivery if we aren’t to become overwhelmed. “There is social media fatigue, with an increasing hunger for quality, long form content,” he says. “Similar to nutrition in food, people will work to develop a healthy, well-balanced media diet. Given the increasing volume of social and news content, there will be a need for more curation, but in many cases the delivery of bite-size pieces is an efficient vehicle for consumption.”

Like social media, television too has seen a shift towards digestibility. Ten years ago, digital television felt as though it had reached a point of no return. Yes, there were American gems hidden away in the farther reaches of networks and channels, but they were so difficult to find that it was impossible to follow a series. Even with the advent of DVRs such as TiVo and Sky+, people constantly moaned about having hundreds of channels and nothing to watch. The live format had broken.

In a few years that has changed entirely.

On demand services now mean it’s unimaginable to think of a time when high quality, easily accessible and, most importantly, finite television content wasn’t available in a few clicks. Netflix allows its huge subscriber base to complete series in their own time. Shows like Orange Is The New Black and House Of Cards are uploaded in one fell swoop. Many predicted this would mean such shows would struggle to get attention in the press and online, but in fact the opposite is true: a slow swelling of interest means they have stayed in the public consciousness for much longer than a few previews for a debut episode.

And when you ask someone whether they’ve watched True Detective or Breaking Bad, they can say something they never would about a website: “I’ve finished it.”

Illustrations by Laurie Rollitt.