Digital Craft

With the 3D printing revolution just around the corner, the recent consumer interest in craft and hands-on making is going digital.

Centuries ago, if you wanted a chair you had to enlist the help of your local craftsman, who would design and construct the piece of furniture by hand. It was a painstaking but personal process, resulting in a one-of-a-kind object. Then the Industrial Revolution came along with its machines that could do the same job as your local carpenter – only faster, cheaper and with greater precision. As technology evolved, the divide between traditional making and digital manufacturing widened. Individuality was replaced with reproducibility. And a lot craftsmanship became a luxury, not a necessity.

Today, that school of thought is changing, thanks to a growing number of designers who are creating innovative tools and techniques that combine hands-on craft and digital fabrication. "When you think about the word 'craftsmanship', it has this nostalgic meaning," says designer Joong Han Lee. "But to me, the word actually means moving forward with evolving technology and finding a new way of creating." Lee, a recent graduate of the Masters program at Design Academy Eindhoven, has done just that with his Haptic Intelligentsia project.

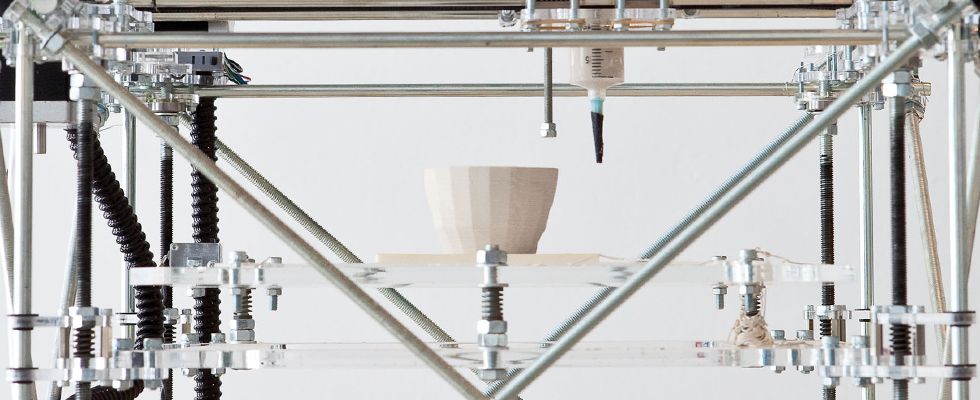

The industrial designer constructed a modified 3D printing machine that uses a glue gun and haptic interface to tactually control the making process. When the tip of the gun nears the invisible computer-generated 3D shape, users feel resistance which in turn provides them with a non-visual guide for creating their object. Using only tactile stimulation, makers are able to construct an item by building layer upon layer of material. The result, as Lee had hoped, is a purposefully imperfect object that shows traces of both the digital tool and the human hand.

When you think about the word craftsmanship, it has this nostalgic meaning. But to me, the word actually means moving forward with evolving technology and finding a new way of creating. "I feel like nowadays when you see digitally made objects, you don’t feel a sense of caring. There’s no personality because everything is made by machines," he says. "I wanted to make a point to show that it’s possible to have this sort of mutual relationship between humans and the machine itself."

Lee isn’t alone in his thinking. The desire to bring a human touch to digital tools has been around in the design world for years.

Front’s 2006 Sketch Furniture project was an early example of the trend. The Swedish design studio found a way to materialise free-hand furniture sketches by capturing the motion data of pen strokes. The digital files were then printed using rapid prototyping, resulting in unique, tactile furniture. Marcelo Coelho, a designer at Zigelbaum + Coelho, believes the movement stemmed from people being tired of living in a perfectly-designed, flawlessly constructed world. "Craftsmen can get to a degree of material expressivity that is unparalleled to any digital fabrication tool," Coelho says. "The motor and sensory resolution of our hands is still far superior to that of any tool, so a well trained hand is hard to replace."

That’s why Amit Zoran and Joe Paradiso, both researchers at the MIT Media Lab, created the FreeD, a handheld milling device. The FreeD works like a traditional milling machine, with a bit that carves an object out of a block of material (in this case, polyethylene foam). But instead of relying solely on computer software to guide the design, the FreeD allows the craftsperson to sculpt and shape an object, much like they would with their hands."The motor and sensory resolution of our hands is still far superior to that of any tool, so a well trained hand is hard to replace." "I started to look for a digital fabrication technique that preserves the maker's control while borrowing some technical abilities from the machine or the computer," says Zoran.

With the FreeD, makers get the best of both worlds – quality control from the computer and creativity from the human mind. It’s an attractive balance. The medical world has already harnessed similar technology for certain procedures, and Zoran believes hybrid devices like the FreeD are a natural fit for designers and craftspeople too. But, he concedes, embracing new methods doesn’t come without its compromises. "By creating something new we might, sometimes, lose old values and abilities. It isn't always something to worry about. But sometimes, by being so exited about progress and change, we give away cultural pieces that took us time to develop and master."

So what do these developments mean for the future of both digital and handmade craft? If you ask Dries Verbruggen, he’ll tell you that eventually that question won’t even matter. Verbruggen, one-half of the Belgium-based design studio Unfold, believes we’re on the cusp of the post-digital era – a time when distinguishing between the digital and analogue ways of thinking will no longer be relevant. Instead, he says, the two will be so irreversibly intertwined that we won’t even notice a divide. "The digital, as a very dedicated thing, will just dissolve into the real world," Verbruggen predicts.

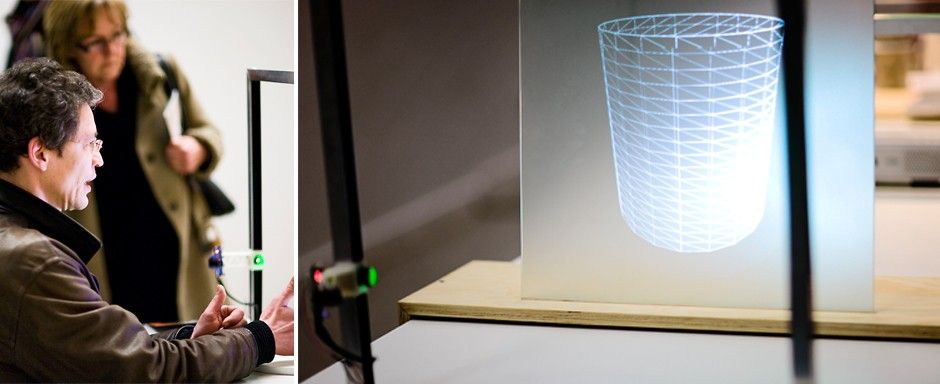

He and his partner Claire Warnier first illustrated this idea in 2010 with L’Artisan Electronique, a virtual pottery wheel that prints out clay objects based on digitally-captured motion data. Most recently, though, the duo has been working on Kiosk, a project that explores a near-future scenario where 3D printing is so commonplace that digital fabrication shops are fixtures in our neighborhoods. He and Warnier envision it as a place where you could fix a broken shoe, materialise an illegal download of an Eames chair or print out a birthday present for a friend. "Sort of like a mobile corner copy shop," Verbruggen explains.

Marcelo Coelho echos this same idea. He says it’s crucial that we find a way to seamlessly blend the digital with the tactile if we don’t want to see the richness of the physical world "replaced by shiny, glass-covered LED screens." He admits it will take some time to get to that point. But does he foresee any roadblocks in making it happen? "No," he says. "Only new opportunities. But only as long as we make digital fabrication tools affordable, open-source, and accessible."