In 2010, Joseph Porcelli noticed that Cory Booker, the mayor of Newark, New Jersey, was personally taking requests via Twitter to shovel out driveways in his community following a winter storm. Porcelli thought he could do even better in applying the convenience of social media to real-world problems. “I wanted to see if I could build on Booker’s success but remove him as a bottleneck,” says Porcelli. As a result, he launched Snowcrew. This social network connects those in need of snow-removal help with local volunteers, who receive real-time requests via email.

“Snowcrew volunteers receive the satisfaction of being of service to their neighbours,” explains Porcelli. “The net result is a closer, healthier, and more resilient community.” To date the site has fielded 1,240 requests for assistance and gathered 4,017 volunteers, according to its creator. It’s an example of what might be called “civic social media”: online social platforms that help connect communities in geographic space rather than just virtual.

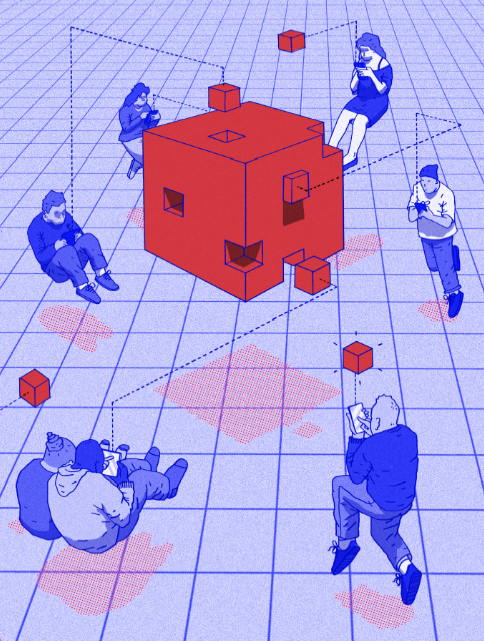

Sites, apps and platforms like these are emerging to fill in the gaps left behind by technologically inept local governments that might not even have a working Facebook page. Rather than trading likes or gaining followers, civic social media focuses on accomplishing real, tangible goals. Civic social media provides an infrastructure of security and accountability that’s often missing in urban life, helps people connect and also has the power to highlight specific issues that need solving.

Take MyCoop, a social network for people living in apartment buildings that aims to challenge the old cliché that neighbours avoid talking to each other. By hosting spaces for online discussion, on topics ranging from block parties and trading old furniture to helping take care of each other’s pets, MyCoop’s founder Alex Norman hopes to group residents together so they can vote on issues and find their own solutions to problems, instead of relying on landlords or building managers to make repairs or create a community atmosphere.

Rather than trading likes or gaining followers, civic social media focuses on accomplishing real, tangible goals Nextdoor, where Porcelli is now a senior city strategist, connects neighbourhoods in order to solve more pressing issues such as sharing news about break-ins or lost pets, as well as swapping contacts for trustworthy babysitters or handymen. Founded in San Francisco in 2010, it helps engage new communities through its network of users and through partners such as the police department in Sacramento, California, and the fire department in Phoenix, Arizona. Each area has its own Nextdoor site that residents can use to connect to each other, particularly in times of need.

Some problems can be dealt with quickly, but others may need much longer-term investment. “When you’re thinking about developing a city, raising $10,000-$15,000 doesn’t scratch the surface,” says Rodrigo Davies, head of product at Neighborly, a San Francisco-based online platform launching in summer 2015. “The problems are much bigger than that.”

Davies points to the example of local governments using municipal bonds to fund projects like highways. The public is rarely made aware of these opportunities to invest in projects like the building of a highway or public square. But there is potential for citizens to purchase these municipal bonds, which offer tax-efficient, low-risk returns, through traditional crowdfunding methods. Such bonds are usually snapped up by specialist broker middlemen; Neighborly will help citizens buy bonds as they are released, making the system more equitable for the state and community members alike. “I think there’s a lot to be gained just by exposing what’s already going on,” comments Davies. “With cities so much of what goes on is totally opaque. If you let people see more of the process than they feel a lot more connected to it.”

Traditionally this hasn’t been the case. The acronym NIMBY, which stands for Not In My Back Yard, describes the negative stereotype of residents who resist any new local proposals that come their way. Brooklyn-based social crowdfunding site IOBY – In Our Backyards – cheekily flips this notion on its head by promoting good vibes round local action. “It’s the idea and act of supporting something and building something together and making positive change that benefits more than just you,” explains Katie Lorah, director of communications and creative strategy for IOBY.

“What we do is reach people that don’t necessarily consider themselves leaders in their communities or would never run for office.” The company, founded in 2008, does this partly by acting like a Kickstarter for local communities across the United States. But, in contrast to the international scope of Kickstarter, IOBY emphasises projects that get up close and personal with communities. In order to become a stakeholder, users can volunteer their time, goods or advocacy, not just their cash.

So far the strategy has paid off. IOBY has run 450 successful campaigns in 100 cities, including protecting bike lanes in Denver, Colorado, installing bike racks in Jersey City, New Jersey, and adding flags to a pedestrian crossing in Memphis, Tennessee. The platform is small-scale by design but huge in ambition, and ultimately capable of activating local community members in a way that few local governments or social networks have achieved.

Your neighbours aren’t vanishing, so much as getting online The internet is closing a gap that exists in urban communities today. What needs repairing isn’t so much our desire for social connection, but the ways in which we reach each other. While our interpersonal relationships with friends and family have benefited tremendously from the internet, our local relationships have not seen the same positive impact. These start-ups are stepping in to bring online connectivity into a new arena.

They underline the idea that cities are already dynamic communities that would benefit from more interconnectivity. These online platforms provide space for residents to interact further with their city by reinforcing that pre-existing infrastructure and improving what we might call its user experience.

Some still have their doubts. “A whole series of changes in our everyday patterns has begun to eat away at the mooring that has long grounded American society,” observes public policy expert Marc Dunkelman in his 2014 book The Vanishing Neighbor. “Adults today tend to prize different kinds of connections than their grandparents,” he says, attributing the loss of society’s connective tissue, in part, to the rise of various social-media networks.

There is, however, potential for these nimble startups to trigger a wider discussion. Civic social media shouldn’t just be the preserve of the private sector. In the future, governments could use the internet to reach out to their citizens across boroughs and at key times in the week, rather than relying on community meetings held in a stuffy central town hall.

These social networks take governance and community building from macro level to micro level and empower us to form our own digital groups outside the purview of Facebook. Your neighbours aren’t vanishing, so much as getting online.