Channelling The Slow

Slow TV is offering a respite from the high-octane television we’re used to, showcasing marathon coverage of ordinary events.

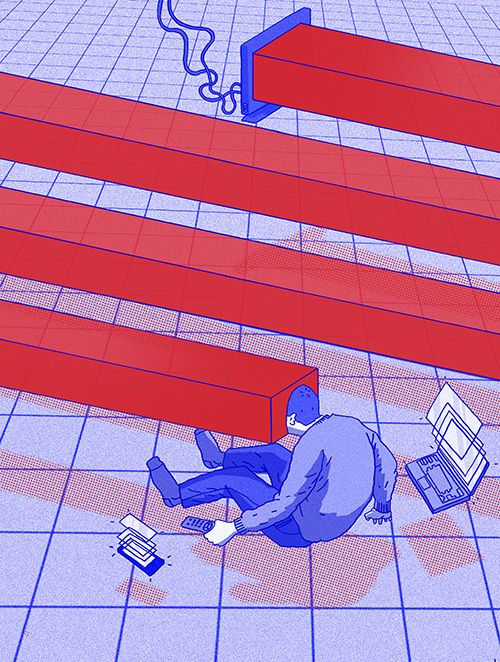

The rate at which we consume media is getting out of hand. Content is put on a plate for us in such a way that we gorge on it. From Buzzfeed listicles to Netflix bingeing, it’s difficult to see where any fulfilment comes from when we’re constantly moving on to the next item. However, there is an alternative: Slow TV is respite from the high-octane television we’re used to, offering marathon coverage of ordinary events. Slow TV storyboards are organic and progressive, as opposed to the scene-hopping television we’re accustomed to. Very little happens, but that’s kind of the point. Slow TV offers a more subdued, introspective and personal type of experience; it’s the quiet antithesis of how content has been evolving.

Those who’ve missed Slow TV’s very steady emergence have been appropriately slow on the uptake. Since 2009, Norway has been producing prime-time television that typically lasts anywhere between five hours and five days. Norway’s inaugural Slow TV offering, Bergensbanen, was a seven-hour, minute-by- minute train journey, and it was uncharted television territory. Norway’s public broadcaster NRK considered not what would be risked by doing this, but what would be risked by not doing this. It aired the programme at prime time on a Friday night and 1.2 million Norwegians tuned in, gaining the broadcaster a market share of 15%.

“An uninterrupted timeline is just a basic way of telling a story,” explains Thomas Hellum, the award-winning television producer behind NRK’s Slow TV movement. “Sometimes content doesn’t have to be more difficult than making an engaging story. The viewer can think: what’s around the next curve? Where do we come out of this tunnel? What could possibly happen? Probably nothing will happen, but you never know.”

Half of Norway’s population tuned in to a 134 hour programme tracking a cruise ship

Two years later 2.54 million of Norway’s five million population tuned in for Hurtigruten, a 134-hour live stream of one of Norway’s most famous cruises. The broadcast set the world record for the longest live television documentary. “We choose to make Slow TV about things that are somehow rooted in Norwegian culture; stories that are worth telling,” says Hellum. “That way we engage a broad audience.” The stories, he adds, need to have facts and content that make good visual television.

Despite being decidedly Norwegian, these shows have found an almost cult following around the world. British Airways has adopted Slow TV as an option for its inflight entertainment (a condensed six-hour version of Hurtigruten to be precise). “We’re always on the lookout for new and interesting content

that gives British Airways passengers the sense of discovery or enrichment during their journey,” says Jason Haney, British Airways brand manager at Spafax, an inflight entertainment curation agency. “There’s also an incredibly relaxing, mesmerising effect to watching this content, which fits in with British Airways’ existing well-being programme.”

Viewing the perspective of a train journey or boat cruise while, on a plane has an irony that is not lost on BA. “It’s engaging, but in a completely different way,” says Haney. “It encourages one to disconnect, become less active, and allows you to be transported from wherever your seat is ‒ the couch in your home or the comfort of your seat on an aircraft.”

Perhaps regular TV doesn’t offer this disconnection. To counter the pace and stress of our modern lives, people have been turning to meditation and mindfulness; Slow TV provides an accessible tool to help get into that headspace. With this in mind, artists and photographers have been turning their hands to the medium, rising to the challenge of making Slow TV that is both engaging and hypnotic, best viewed in high definition, streamed or downloaded from the internet.

London-based photographer Toby Smith recently filmed a six-hour train journey from Dewanganj to Dhaka in Bangladesh in stunning 4K resolution. Presented without a single dropped frame or interruption to either image or sound, it pushes the technical bounds of the medium.

“As the films are not constructed, edited or constrained to specific chapters, storyboards or scheduling, they make for a genuinely relaxing and intriguing experience,” explains Smith. “They can be used as on-screen wallpaper, an escapist journey or just a way of teasing the digital knots out of a stressful day.”

The idea of repurposing a television or computer screen into decorative, ambient furnishing or perhaps relegating it to the second most important screen in the room is becoming more commonplace. Where families would make an event of gathering round the wireless, the radio has for many become background noise. Is the same thing happening to the television? Is it just a comfort to have something on the screen while we work or scroll through social media? BBC Four thinks not, having recently brought Slow TV to British television with a series of programmes under the banner BBC Four Goes Slow.

It encourages one to disconnect, become less active, and allows you to be transported from wherever your seat Jason Haney, British Airways brand manager at Spafax

The most popular offerings in its Slow TV season to date, Dawn Chorus: the Sounds of Spring and a documentary about the making of a glass jug; both attracted nearly half a million viewers. “BBC Four is always looking to surprise its audience with new and innovative programming,” says Owen Courtney, BBC Four’s head of planning and scheduling. “In an ever more frantic world, BBC Four wanted to give viewers the chance to breathe out and take time to enjoy the journey, experience and process in a different way.”

The BBC may have pipped US television to the post, but only because in the US the Slow TV debut has been saved for the most frantic day of the year. The Travel Channel will air Slow Road Live, a serene 12-hour road trip (in real time), on Black Friday (27 November) as a way to unwind and escape from the no-holds-barred street fight that the day of discount shopping has become.

Aside from the educational or relaxing aspects of this timely practice, there may be a more cynical motivation to producing presenter-less, dialogue free, unedited television. Is Slow TV a response to austerity? Slow TV could prove to be an effective, economical way to fill schedules. Yet it’s TV that speaks to the masses at the end of a long day. It’s TV for thinkers and TV for the thoughtless, or perhaps just TV that requires as much thought as you’re willing to give it.