Beyond Gender

There’s only two options, you’re either a boy or a girl right? No, not really. It seems our attitudes to gender are becoming more open and fluid by the day.

“Fishy, fishy in the brook, father caught it by the hook, mother fried it in the pan, baby ate it like a man”

In our not-too-distant past, gender roles were largely straightforward, as things went. There was a direct link between gender, aspiration and expectation, such that women were generally expected to keep house, and men to bring home, if not the bacon, then the folk tale fishy in the brook.

Fast-forward to today: globally, the number of female students in tertiary education has grown since 1970, according to UNESCO figures; in North America, Western Europe, Latin America and Central Asia, women’s enrolment rates surpass those of men. Men increasingly voice support for the feminist movement, for example via HeForShe, a solidarity campaign for gender equality. Time magazine in 2014 trumpeted that we are at a ‘transgender tipping point’. So the role of fathers is once again coming into the limelight, as the number of stay-at-home dads increases, and millennial parents search for ways to equalise opportunities for men in the home. Today, it seems, gender is up for grabs.

New Generation, New Gender Agenda

It’s perhaps no surprise that socially-progressive millennials (born between 1980 and 2000) are leading the charge against traditionally accepted gender expectations. The legacy of then social change and global feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, this generation has fewer attachments to traditional social, political and religious institutions than previous generations did. More than two-thirds (68%) of US millennials support same-sex marriage, reports the Washington DC-based Pew Research Centre; in the UK, millennials are more relaxed than older generations were, at their age, about homosexuality and non-traditional family structures, according to the British Social Attitudes survey.

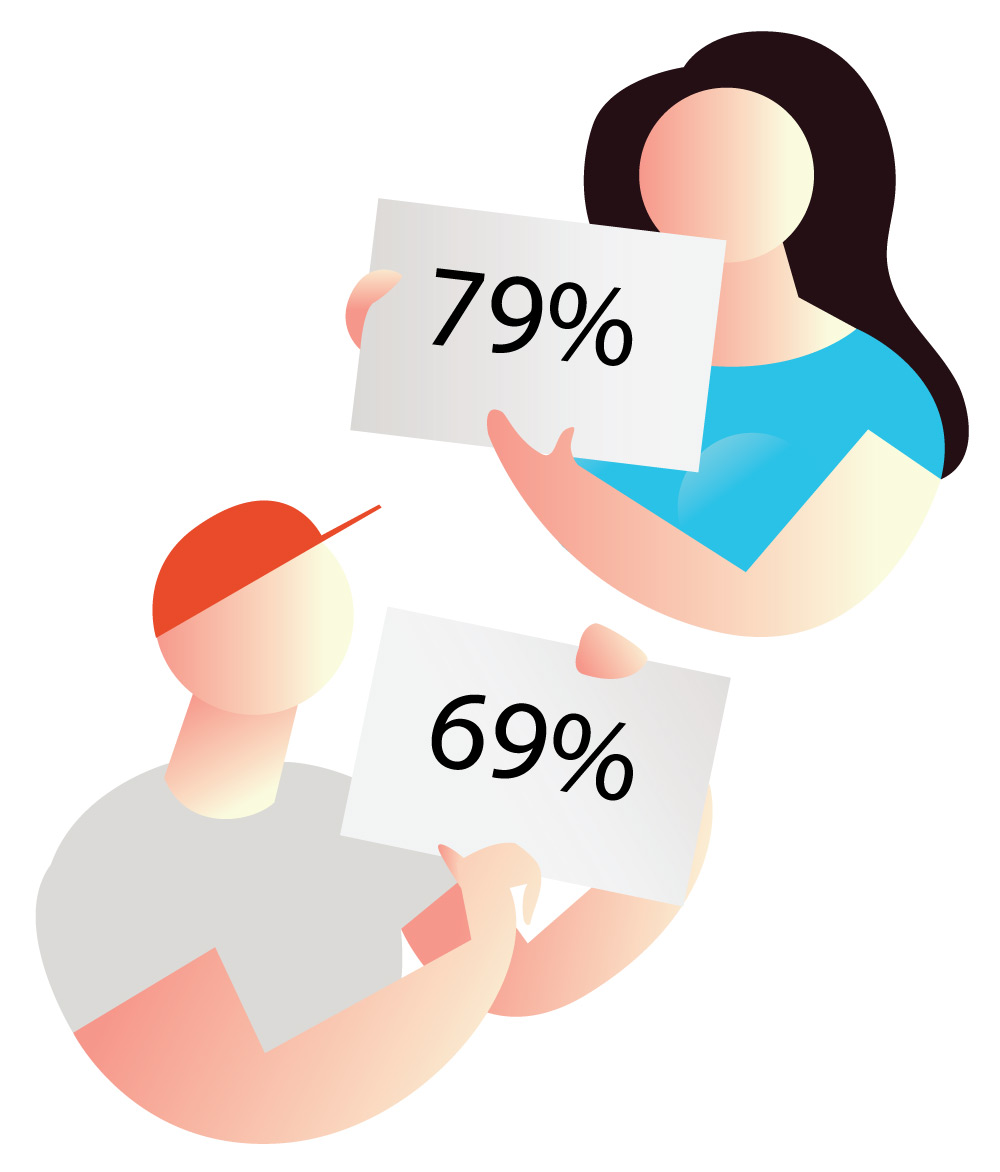

Protein conducted its own survey in late 2014 on millennials’ attitudes to gender, which confirms prior studies and assumptions about this group. Nearly seven out of 10 people (68%) say that gender is less important to their generation than it was for their parents, while four in five people (79%) say gender roles have blurred. Beyond blurring, in fact, millennials overwhelmingly question traditional gender binaries, with seven in ten people (69%) saying there are more than two types of gender. This state of flux brings with it both excitement and anxiety, as millennial men and women navigate new gender ground.

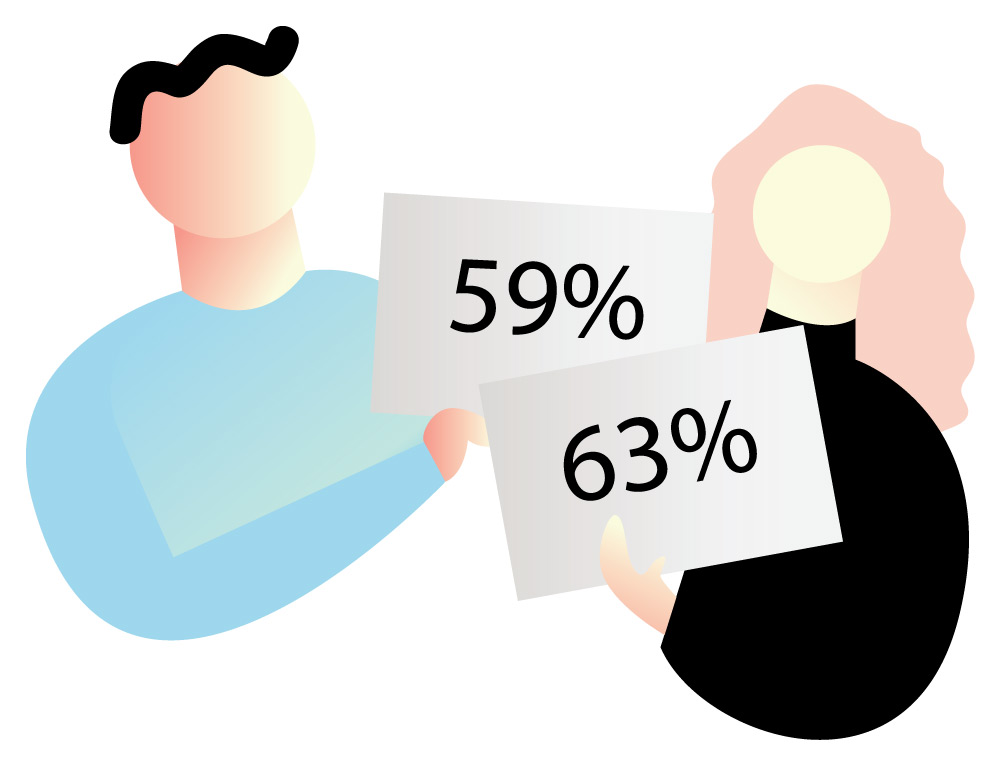

Protein Gender Survey: 63% of females and 59% of males believe that that children should grow up in a gender neutral environment

In today’s society, gender has become a fluid concept for many. However, this fluidity comes hand in hand with certain tensions

“In today’s society, gender has become a fluid concept for many,” says Linda Tuncay Zayer, co-editor of Gender, Culture, and Consumer Behavior. “However, this fluidity comes hand in hand with certain tensions. For example, while most millennial men may find being an involved father is a big part of masculinity, that doesn’t necessarily mean they would not feel some hesitation about being a stay-at-home dad. These tensions existed for Generation X men as gender roles changed, and they exist for millennial men too.”

Similar tensions exist for women, of course. “Millennial women are normally clued-up about feminism – they expect to be seen as capable intellects,” says Kathryn Lofton, chair of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Yale University. But once women reach their childbearing years, Lofton says,“they realise they can sacrifice themselves on the altar of a career, or on the altar of the home. Many young women feel as if there’s going to be a moment in the future that will test their feminism: home or work? There’s a sense of existential questioning.”

Further, experts insist that any changes in thinking about notions of gender are far from universal, entwined as they are with issues of class and education.

“We’re seeing the first generation who grew up learning the stuffthat’s taught in women’s and gender studies programmes,” says Kate Bornstein, author of My New Gender Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Achieving World Peace Through Gender Anarchy and Sex Positivity. “As soon as they got to college, they opened Judith Butler and Leslie Feinberg and my books ,and they thought: ‘This could be fun!’ But this cutting-edge front (of people questioning gender norms) has more to do with class and education. A lot of people didn’t go to college, and didn’t grow up learning that.”

Tuncay Zayer agrees: “Gender roles can be influenced by race, ethnicity, age, life stage, upbringing and sexuality, among several other factors, so we need to be careful not to generalise an entire generation.”

Blurred Lines

In culture at large, at least in privileged, first-world circles, we are seeing the slow but steady erosion of some gender customs and stereotypes – in beauty, fashion and the media, for instance. The men’s beauty industry is booming, Tuncay Zayer says, now that “having an attractive appearance is no longer a metro sexual thing – it’s for the everyday Joe”. Going beyond men’s moisturiser,male make-up is colouring outside the gender lines, from Tom Ford’s and Marc Jacobs’s men’s beauty collections (the latter including a skin brightener and an eyebrow-grooming gel, bearing the tagline ‘Boy Tested, Girl Approved’) to gender-neutral make-up brand Enter Pronoun. The trends break geographical boundaries, too: South Korean men make up the largest market (21% of global sales) for men’s skincare in the world, according to market research firm Euro monitor, with growth expected to continue.

Protein Gender Survey: 79% of males and females said that gender roles have blurred. 69% of males and females believe there are more than two types of gender

Fashion designers are increasingly turning to unisex fashion, with androgynous oversized tops here and skinny jeans aplenty there. For the spring/summer 2014 collections, London designer Richard Nicoll and artist Linder Sterling launched a unisex line called S/He, while Paris-based Canadian designer Rad Hourani introduced a unisex couture collection in 2014. Menswear designer J W Anderson’s 2014 collection for Spanish brand Loewe was shown on male and female models, while Hedi Slimane sent men and women down the runway in glamorous but none the less gender-neutral outfits for his spring/summer2015 Psych Rock collection for Saint Laurent.

We’re seeing a lot of different ideas about gender normativity. We are, hopefully, witnessing the slow death of the rigid alpha male archetype

Blurring lines of a different fashion, new media outlets are challenging gender assumptions of parenthood. On the websites Mothers Meeting and Motherland, women decline to be identified primarily by their reproductive abilities: parenting is just one of the topics, among fashion, art, culture, food and travel, that readers discuss. For millennial dads, the handsome Kindling Quarterly is quietly transformative in its thought-provoking presentations of current-day fatherhood. “I wanted a place to discuss a more feminist, more engaged, more thoughtful version of fatherhood,” says Kindling publisher and editor David Michael Perez. “We’re seeing a lot of different ideas about gender normativity. We are, hopefully, witnessing the slow death of the rigid alpha male archetype – it’s increasingly anachronistic and unnecessary. But there’s still a lot of hesitation among men to explore the emotions that come up around parenting, and around their own experiences with their fathers.”

Men, Women And The Rest Of Us

Key to the move towards a more nuanced understanding of gender identity is the growing acceptance that gender is not a clear-cut, black and white question of man and woman. As author Kate Bornstein says; “Transpeople aren’t really interested in traditional gender roles either”.

On a governmental level, change is slowly being effected, as countries around the world rewrite their laws to recognise the rights of transgender people. In Argentina, adults may change their gender, image and birth name on official documents, without first having surgery or a psychiatric diagnosis. In Australia and New Zealand, citizens may choose to be listed as male, female or indeterminate in their passport. In India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal, the countries’ highest courts have all passed landmark rulings recognising a third gender for people who do not wish to identify as male or female. In early 2015, the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh elected MadhuBai Kinnar, India’s first transgender mayor.

In many ways, too, mainstream culture is increasingly, ever-so-gently challenging the binary assumptions of gender. In 2014, transgender actress Laverne Cox was nominated for an Emmy award for her work in the television series Orange is the New Black. The critically acclaimed drama series Transparent portrays a middle-aged transgender woman as she transitions from Mort into Maura. Last year, the Broadway musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch, a tale of a transgender rock ’n’ roll singer, won four Tony Awards. Off stage, the highest-paid female CEO in America, Martine Rothblatt, happens to be a transwoman. And, in the UK, politician Emily Brothers, who will stand in the May 2015 general election, is the first openly transgender person to run for the UK parliament.

Some high-profile companies have begun thinking outside the gender-binary box as well. Facebook users may choose from some 50 gender options including ‘polygender’ and ‘intersexperson’. Google’s social network, Google+, simply leaves a customisable space to let users describe their gender however they want – or not at all.

But Bornstein remains cautious of overstating mainstream acceptance of transgender people and those who call themselves ‘non-binaries’. “There is still a lot of discomfort when it comes to dealing with more than two genders,” she says. “The people who are moving away from the binary are still outlaws. They’re still shunned, even in the most liberal, urban centres. After Ohio transgender teenager Leelah Alcorn’s suicide, the groundswell of support for trans rights on the internet was astounding. But so was the backlash.”

G Is For Gender

As the waves of progress wash forward, our best hopes lie, perhaps, in educating future generations, and providing environments which are free of gender stereotype for developing minds.

New initiatives question the unrelentingly gendered options in toys and clothing for children. In Australia and the UK, advocacy groups Play Unlimited and Let Toys Be Toys work to eliminate the gendered marketing of toys to children; PlayUnlimited launched the high-profile No Gender December campaign in the lead-up to the gift fest of Christmas 2014.Similarly, the Pink Stinks campaign targets the products, media and marketing that prescribe heavily stereotyped and limiting roles to young girls. Meanwhile, seeking to clothe their offspring in unisex outfits designed to please children – not just boys or girls – millennial parents are turning to kids’ clothing labels BoboChoses (Spain), Tootsa MacGinty (UK), Raised Wild (US), MiniRodini and Polarn O Pyret (both Sweden).

However the groundbreaking work in girls’ and women’s empowerment has not yet been matched by similar efforts in boys’ and men’s awareness-raising. “There is a neglected area of dialogue when it comes to boys and ideas about masculinity,” says Tuncay Zayer. “Efforts are increasingly being made to consider how this half of our society may create spaces for themselves in more gender-fluid times. In 2014, president Barack Obama launched My Brother’s Keeper, a nationwide mentorship programme to help boys and young men of colour. Similarly in Barcelona, the Boyhood Project advocates raising and educating emotionally intelligent boys to thrive in the world. Elsewhere, film-maker Jennifer Siebel Newsom’s The Mask We Live In, which explores how a narrow definition of masculinity harms boys and society at large, will premiere at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.

On an institutional level, early years education in more progressive countries has much to teach the rest of us. Here, there are conscious efforts to wipe out gender discrimination from the youngest ages. In Sweden, for instance, the national curriculum for preschools requires early years centres to ‘counteract traditional gender patterns and gender roles.’ Ideal examples of the gender-neutral approach, Stockholm’s Nicolaigården and Egalia preschools work to free children from gender stereotypes: for example, teachers try to avoid ‘him’, ‘her’, ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ by using gender-neutral pronouns and calling all children ‘friends’.

Institutions in other countries have had to battle less tolerant mindsets. Witness the commotion and handwringing that ensued when a primary school in East Sussex, UK, introduced unisex toilets last year to, the headteacher said, “prevent any transphobia at the school.”

Gender Evolution

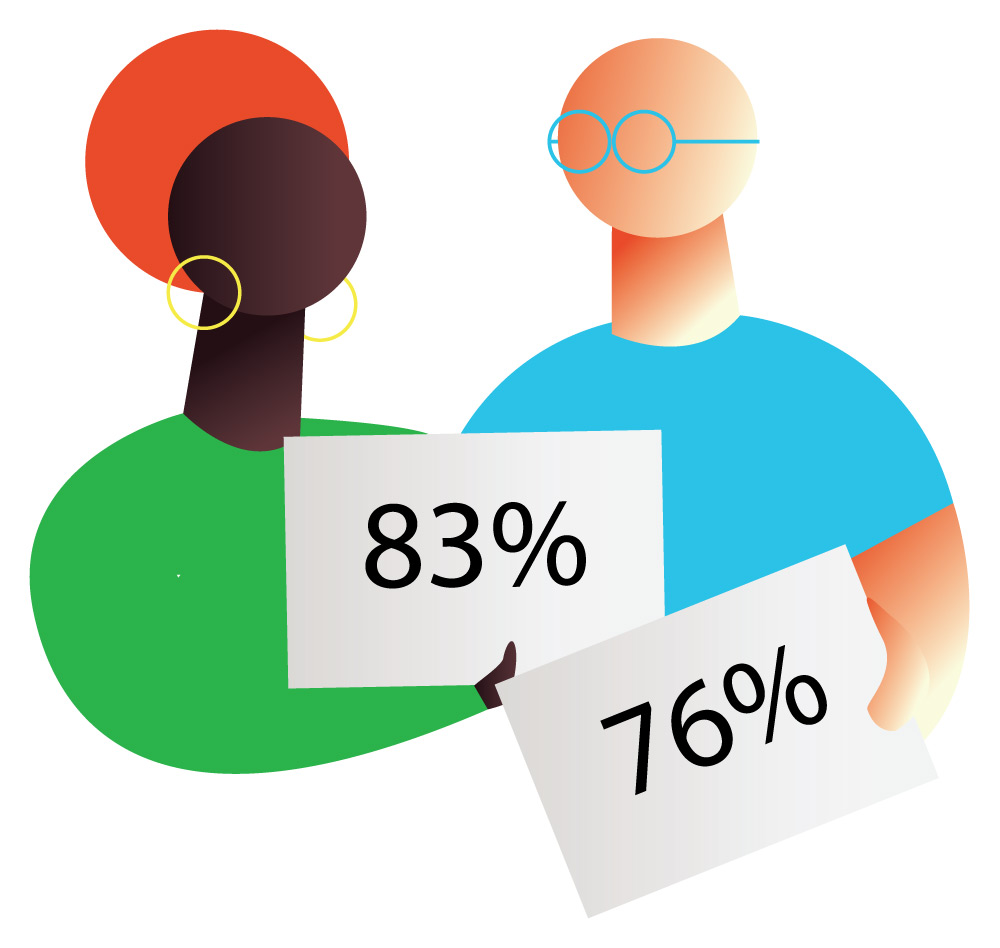

Despite changing assumptions of gender, and ever-louder voices calling for equal treatment of men, women and, yes, the rest of us, gender inequality remains rife. Indeed, our survey found that most people (83% of women and 76% of men) do not believe that all genders are treated equally by society in their country. The facts are sobering: while the number of women heading Fortune 500 corporations reached a high in 2014, that number – 24 – represented just 4.8% of these companies. Only seven of 150 elected heads of state in the world are women. Internationally, the gender pay gap still exists, even in the most progressive Scandinavian countries. Gender inequality at the macro level trickles down to the street: the Everyday SexismProject, which catalogues real-life instances of sexism – from casual to outré – is just one example bearing witness to the many ways in which women still experience gender discrimination in every part of the world, every day.

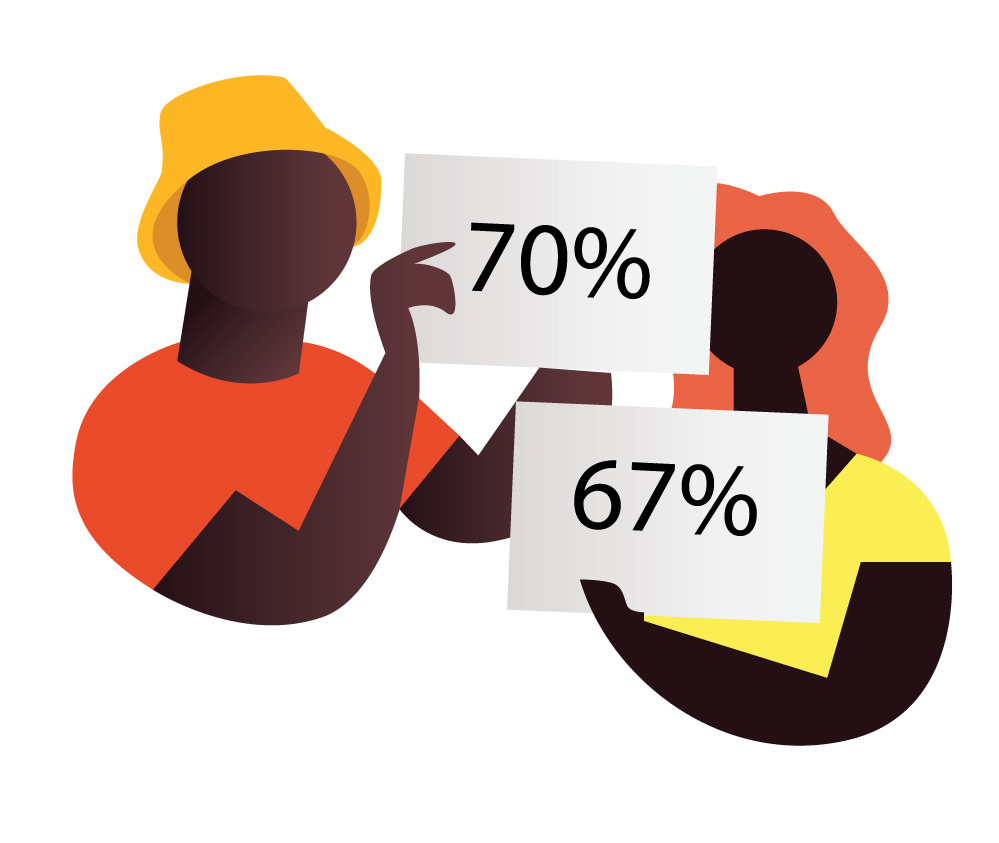

Protein Gender Survey: 67% of females and 70 % of males confirmed that gender is less important for their generation thanit was for my parent’s generation

Ultimately, while society has taken great steps forward over past generations, stereotypes of gender norms remain so deeply rooted that it would take a complete and sustained overhaul of institutional and public policy and social expectations before we attain a state resembling gender equality.

Protein Gender Survey: 83% of females and 76% of males disagreed with the statement that all genders are treated equally by society in their country

As the traditional assumptions of gender are increasingly put into question, these could be transformative times. Lofton, the Yale professor, urges the necessity of re-examining ‘there productive narrative’ – not only the act of reproduction, but also the entire tragicomedy of rearing a child, and the expectations and responsibilities that come with it. Bornstein, the trans activist and author, looks forward to a future where language more accurately reflects the ambiguity of gender – perhaps within creased use of the gender-neutral pronoun ‘they’ instead of ‘he’ or ‘she’. Elsewhere, Perez, the publisher, is keen to contemplate “what men look like outside of patriarchy”.

Consumers can be powerful mechanisms for change, rewarding companies, for example, that depict men and women in advertising in ways that are both appealing and responsible

Undoubtedly, what Tuncay Zayer calls “institutions of power” – government, industry, the media – have a responsibility to make lasting transformations that equally value people, regardless of their gender. But people on the ground, too, have choices to make. “Consumers can be powerful mechanisms for change, rewarding companies, for example, that depict men and women in advertising in ways that are both appealing and responsible,”

Tuncay Zayer explains. Her recent research found that many advertising executives “showed concern for portraying women in a positive light, while men did not receive that same consideration”. “It is still common practice in the industry to portray men as bumbling dads,” she says. Such tropes demean us all.

As individuals, there is much soul-searching to be done as we attempt to tease apart the tensions that accompany an ambiguous gender paradigm. For most of us, the tussle with gender dynamics will take place not on an abstract, societal level, but in our own lives. Beyond male make-up, will we – can we – truly allow ourselves the freedom to redefine widely accepted notions of maleness and femaleness?

“There’s a whole gamut of expectations that people have,and we’re trying to evolve as quickly as we can,” Perez says.“On a personal level, the more my wife and I can see each other as partners outside of gender dynamics, the happier we’ve been, and the happier our family has been as a whole. But we’re still gendered people, and we’re still navigating this terrain.”